002 SANDWICH:教えることと学ぶことの間に存在する未完のスペース Manifold(マニホールド)の冒険

プラープダー・ユン

小説家・アーティスト

私は16歳か17歳くらいになるまでパフォーマンス・アートについて何も知らなかった。

アートのすぐれた、そしてよくある手法のひとつとして今ではすっかり確立されたパフォーマンス・アートだが、自分がその存在について知ったときは、「これをアートと呼ぶのか?」というような態度だったと思う。ティーン時代は、内向的な自分に誇りを持っていたから、アーティスティックなものかどうかにかかわらず、あらゆる自己顕示的表現を避けて通った。だから最終的にパフォーマンス・アートという概念に馴れ、、またその分野のパイオニアたちの何名かに感銘を受けてからも、この手の芸術的な自己表現は、自分とは無関係だと、確信に近い感情を抱いていた。

アートスクールの同級生たちの多くがそうだったように、ヨーゼフ・ボイスのコンセプチュアルなパフォーマンスを、まったくわからないながらに知的な刺激を受けた。アメリカ人アーティスト、クリス・バーデンが1971年の「シュート」というパフォーマンス作品のなかで、自分の腕を他人に撃たせたと知ったときには、衝撃を受けたし、またおそらくサディスティックな意味で興奮した。学生時代は、その表現活動において、演奏や「ハプニング」を重視した多国籍のムーブメント、フルクサスに夢中になった時期もあった。それでも、私は自分には「オーディエンス」が誰もいない状況に満足し、パフォーマンスに関わろうとしたことはこれまでなかった。

だから東京都現代美術館で大成功した名和晃平の個展のクロージング・イベントのために、8月28日にパフォーマンスでコラボレーションしようと誘われたとき、私の最初のリアクションは「私はパフォーマンス・アーテストではないのに、何をやればいいっていうんだろう?」というものだった。バーデンが自分の腕にやったように自分を体のどこかを撃つような真似をするつもりはなかたし、ヨーゼフ・ボイスが1974年に『コヨーテ -私はアメリカが好き、アメリカも私が好き』という作品でやったように、生きたコヨーテと同じ空間に入るつもりもなかった。

もちろん、不安を別にすれば、イベントに参加できることを名誉にも感じていたし、わくわくしてもいた。けれどもパフォーマンスという要素が唯一の不安の種というわけでもなかった。そのあとすぐに、とても広いスペースで、横15メートル、高さ5メートルの巨大な壁を使って、またはその前で「何か」をやる、それも2時間にわたって、という計画を知らされた。プロのパフォーマンス・アーティストだって、こんな条件だったら少なくともちょっとは心配するはずだ。

さらに、その巨大なスペースは、名和氏の個展の一部として使われていて、公共の彫刻作品として計画されている「マニホールド」という作品の模型のパーツが展示されているところ、つまり「マニホールド部屋」というわけだった。この作品は、完成したら韓国の巨大なショッピング施設の前に置かれることになっていて、名和氏の近年の彫刻に対するアプローチを代表するものであり、物理的にもコンセプトという点でもとりわけ大規模なものである。名和氏はおそらくこの言葉を意図的に交換可能なものとして解釈しているだろうけれど、「マニホールド」の非数学的な定義は、「多様性」や「多岐管」に近い。そしてわれわれのパフォーマンスは、この作品の新たな「フォールド(層)」、または延長として機能するということだった。

最初は名和氏とふたりで、壁にドローイングをしようと考えた。2時間かけてドローイングをすることは十分容易だとしても、ドローイングのペース、スペース、デザインをどう調和させていくかという疑問が残る。自由なコラボレーションや、具体詩は楽しいし、解放的な気持ちにさせてくれるけれど、このふたつを足したとしてもそれ自体は「パフォーマンス」ではない。パフォーマンスにおいては、常にオーディエンスが決定的な要素だし、彼らに何を見せたいのか考えなければならなかった。

名和氏のサンドイッチ・スタジオで、高い衝立を使って何度かテスト・ドローイングをした。衝立は、スタジオを使うアーティストたちが実際の展示スペースにおいて作品がどう見えるかを想像できるように、つまりまさに今回のような目的のために、ミュージアムやギャラリーの白い壁を真似て作られたものだった。サンドイッチのスタッフの数人が新しいドローイングツールを発明するのを助けてくれ、学生たちがパフォーマンスの準備やリハーサルで助手の役目をしてくれた。ラインの質や全体的な操作具合を比べるために、さまざまなタイプの表現手法を試した。創作のプロセスなかでもこの段階は、だいたいの場合、フラストレーションと失望がつきものだ。なぜならアーティストがどれだけ経験を積んでいても、どれだけその手法に馴染みがあったとしても、写真家にとって一人ひとりの被写体が新しいチャレンジであるように、新たな作品は多かれ少なかれ出発地点だからだ。そして、新しい出発点は予想しなかった間違いや、満足できない結果に満ちているというのが決まりなのだ。

衝立で何度か試してみたあと、ドローイングでコラボレーションするかわりに、名和氏が壁画をつくる間、私が詩を朗読するということに決めた。最終的には、名和氏の個展に対する一種のお別れの儀式になるわけだから、言うなれば名和氏が「主役」を務めるやり方のほうが、筋が通っていた。

というわけで、私の創作をまったく知らないであろう、少なくとも100人にはなると予想される、大半は日本人という美術館のビジターたちの前で、2時間にわたって詠むための詩を構成する言葉を、私は何日もかけて練った。ドローイングという作業は多大なる喜びを与えてくれるけれども、私のスタイルは、典型的な抽象表現主義になりがちなので、ドローイングのかわりに詩を朗読することになってうれしかった。それでも、自分の不安な気持ちが薄くなったということはなかった。

パフォーマンスの日が近づいてきたときに、突然、自分のパートについて別のアイディアが浮かんだ。名和氏が登場する数分後に、用務員のユニフォームを着た私が壁の前に登場し、名和氏がドローイングをする際に床にたれる余剰のペンキをモップで拭き取り、それを使って横長の作品を作るのだ。「アート・クリーナー」の役を引き受けつつ、「消す」かわりに「作る」というアイディアだった。このアイディアは、「マニホールド」のコンセプチュアルな側面と微妙に関係しているとも考えた。そのうえ、これならパフォーマンスにユーモアを加えることができる。いつだって私はアートにおいて、もっと言えば何においても、ちょっとしたユーモアが入っているのが好きなのだ。

パフォーマンスの日はやってきて、去っていった(パフォーマンスの間、Kawolという素晴らしいミュージシャンがコラボレートしてくれたのもとても恵まれていた)。パフォーマンスは、当初に計画していたものとすっかりかけ離れたものになったわけだが、この経験は満足できるものだったと考えた。何度も失望したり、その過程で考えついた方法を捨てたりしながら、名和氏とふたりで準備やリハーサルに費やした時間を振り返って、それをすべて経験してよかったと思った。人は失敗したとき、多くのことを学ぶものだ。サミュエル・ベケットが好んで言った言葉がある。「挑戦して失敗したなら、もう一度挑戦して、前より上手に失敗しろ」。

Photo by Sandwich Team

Kohei Nawa-SYNTHESIS 2011, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, Photo: Sho Ogasahara, © 2011 Kohei Nawa

Sandwich: Unfinished Space Between Teaching and Learning 002 (Manifold Adventure)

I knew nothing of Performance Art until I was about sixteen or seventeen, and when I first learned about it I probably had the "You call this art?" sort of attitude toward what is now generally considered to be a rather "conventional" and benign artistic practice. A proud introvert in my teens, I shunned all types of exhibitionism, be it artistic or otherwise, so even though I finally warmed to the idea of Performance Art and was even genuinely impressed by some of its pioneers, I was still quite certain that this kind of artistic expression was not for me.

Like many of my art school peers, I was intellectually stirred by the conceptual performances of Joseph Beuys, though I can't say I understood any of it. I was shocked and excited, perhaps sadistically, when I learned that American artist Chris Burden had someone shoot him in the arm as a performance piece (Shoot, 1971). And for a period during my college years I was obsessed with Fluxus, the international movement that emphasized play and "happenings" in its art. Yet I never attempted to get involved in performance, preferring solitude as my audience.

So when Nawa Kohei asked me to collaborate with him in a performance at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, on August 28th, as the closing event of his highly successful solo exhibition, my initial reaction was, "I'm no performance artist. What the hell am I going to do?" I was ready neither to shoot myself anywhere, as Burden shot his arm, nor put myself in a room with a live coyote, as Joseph Beuys did for his legendary I Like America and America Likes Me piece in 1974.

Of course, apart from the anxiety, I also felt extremely honored and thrilled to be part of the event. However, the performing part of it was not the only concern. I soon learned that we would be doing "something" in a very large space, on or in front of a huge wall (about 15 meters long and 5 meters high), and for two hours! I think even a professional performance artist would have worried about that condition at least a little bit.

In addition, that very large space was currently the section in Nawa-san's exhibition where the model parts of his very large proposed public sculpture, Manifold, were displayed; it was the "Manifold Room." Soon to be erected in front of a gigantic shopping complex in South Korea, Manifold is one of Nawa-san's more recent sculptural approaches, and one that's particularly ambitious, both physically and conceptually. The general, non-mathematical definition--though Nawa-san's use of it is probably intentionally interchangeable--of "manifold" is close to "diversity" and "multiplicity," and our performance was to function as another "fold," or an extension, of the sculpture.

At first, Nawa-san and I thought about making a mural drawing together. To draw for two hours would be easy enough, but the question then became how to harmonize pace, space and design of the drawing. Free collaboration and concrete poetry are both always fun and liberating, but they're not, even when put together, "performances" in themselves. The spectators are a crucial element of any performance, and we had to consider what we wanted to present to them.

At Nawa-san's Sandwich studio we made several test drawings on a high partition built for this exact purpose: to mimic the white museum/gallery wall so that artists who use the studio can imagine what their works would look like in real exhibition space. Several Sandwich staffers helped to invent new drawing tools and some students assisted our preparations and rehearsals for the performance. We also tried various types of mediums to compare line qualities and their overall controllability. This part of the process usually comes with frustrations and disappointments, for no matter how experienced an artist one is, no matter how familiar with the mediums, every new work is always, to a certain extent, a new beginning, as every subject is a new challenge for the photographer. And new beginning is, as a rule, full of unexpected errors and unsatisfying results.

After a few trials on the partition, we decided that I would, instead of collaborate on the drawing, recite poetry while Nawa-san worked on the mural. It made more sense for Nawa-san to "take center stage," so to speak, because, after all, this was going to be a kind of farewell to his exhibition.

So, for days I worked on the words I was to recite for two hours in front of presumably at least a hundred, mostly Japanese museum visitors who were not at all familiar with my work. I was happy to be reciting poetry rather than drawing--drawing gives me tremendous pleasure but I feel that I tend to draw in a very typical Abstract Expressionist style--but the level of anxiety did not decrease.

When the performing date neared I suddenly had a different idea for my part of the act: I would appear in front of the wall several minutes after Nawa-san, dressed in a janitor's uniform, use a mop to absorb the excess pigment dripped onto the floor from Nawa-san's drawing, and make horizontal paintings with it. The idea was to take the role of an "art cleaner" but "make" rather than "erase." I thought the idea itself also related subtly to the conceptual aspect of "manifold." And it would add humor to the performance. I always like a touch of humor in art, or in anything for that matter.

The performing day came and went (we were also very lucky to have Kawol, a wonderful musician, collaborate with us throughout the performance), and I thought the experience was satisfying, even though the act turned out to be nothing like the idea we had in the very beginning. Thinking back to all the time Nawa-san and I spent preparing and rehearsing, with all the disappointments we felt and the solutions we had to discard in the process, I was very glad we went through all of it. One learns a lot when one fails. As Samuel Beckett liked to say, if you've tried and failed, try again and fail better.

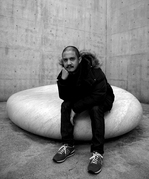

プラープダー・ユン

1973年生まれ、バンコクに拠点を置くタイの小説家・アーティスト。

多数の小説、短編小説やエッセイのコレクションを出版し、「ライ麦畑でつかまえて」「時計じかけのオレンジ」のような現代英語の古典文学もタイ語に翻訳。2002年に、彼の短編小説のコレクション「存在のあり得た可能性(英題:Probability)」で、タイで最も権威ある東南アジア文学賞を受賞。 他、プラープダーは定期的に日本で雑誌に執筆したり、アートのエキシビションを開催。また、映画「地球で最後のふたり」「インビジブル・ウェーブ」(主演:浅野忠信)の脚本や、現代アーティスト名和晃平の様々なアートプロジェクトにも協力。

Prabda Yoon

Born in 1973, a Thai writer and publisher based in Bangkok. He has published numerous novels, short story collections, and essay collections. In addition, he has also translated modern English-language classic literature such as The Catcher in the Rye and A Clockwork Orange into Thai. In 2002, his short story collection, Kwam Na Ja Pen (English: Probability), won the SEA Write Award.

Apart from working in Thailand, Prabda has regularly written for Japanese magazines and exhibited artworks in Japan. He has written 2 screenplays for films starring Tadanobu Asano and he is presently collaborating on various art projects with Japanese contemporary artist Kohei Nawa. His literary works have been translated into Japanese, of which the most recent is the novel Panda.

Japanese Translation: Yumiko Sakuma