Beyond Disasters - Telling the Stories <1>

An interview with artist and writer Kobayashi Erika

I Write Because I Don't Know

March 29, 2022

[Special Feature 074]

For this special issue, Beyond Disasters - Telling the Stories (see an overview here), we interviewed Kobayashi Erika, a creator of novels, manga, and installation works based on extensive research and covering historical episodes of vast scope such as the discovery of radiation, world wars, and disasters. We asked her why she creates stories and how she speaks of the cataclysms throughout history.

In My Hand - The Fire of Prometheus

In My Hand - The Fire of Prometheus2019 C-print 43.2cm×35.6cm (set of three), photo by Nogawa Kasane

- ──How did you spend your time during the past year of the Covid-19 pandemic?

- The nursery school my child attends was closed for the first three months due to the spread of Covid-19, so we stayed at home together. But the school was reopened after that, and since then, I have been living as normal for the most part.

- ──Have the new lifestyles and the changes in the way we feel about time and space brought about by Covid-19 effected your creative work?

- I feel that the most frightening thing is the way people react to threats that cannot be seen with the eye, and that is not limited to the changes due to Covid-19.

For example, soon after Covid-19 emerged, there was a rise in exclusionism against travelers from overseas, as though they had brought the virus with them, and blame was shifted to the weak. And after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, people disliked seeing cars with Fukushima license plates for no reason, claiming they had brought the radiation with them. It's happening again this time regarding Tokyo plates, as though they are bringing the virus with them.

We have not managed to learn how to handle the fear of that which we cannot see. Unable to make use of the lessons we learned from the accident at the Tokyo Electric Fukushima nuclear power plant, so as usual, we resort to discrimination with no scientific basis and blame everything on the weakest among us, and it makes me so angry to see that happening.

- ──Many of your works touch on the story behind cataclysms such as war and earthquakes. Why is that?

- The first thing that always comes to mind for me is wonder. By that I mean wondering why it is that I'm alive now to face this situation. I believe I want to know the reason why.

For example, after the 2011 earthquake, I wanted to know why was it that now, on a daily basis, in order to buy even a single mushroom, I had to worry about whether it had been tested for radiation. Today, when a cataclysm occurs, the focus is almost exclusively on getting the situation under control and solving it. Of course that is what needs to be done first. But actually, I want to know why it happened. What was the cause that created the situation we have now? What were the plans and decisions made, and by whom, that led to the present? In order to do that, we have to look back at history.

For example, we are repeatedly taught by television and school from childhood about the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the tragedy it caused. But it was not until adulthood that I learned that Japan had also been trying to develop an atomic bomb as well. I was shocked at the time to imagine that we had been developing the atomic bomb to drop on another country, such as the target of Saipan. I felt that it was impossible to continue talking about it while ignoring that fact.

And this is true for nuclear power as well. What do the scientists and politicians who thought that was a good thing think about the current situation, and how will they take responsibility? These are the questions I want to ask. And that is not to say that one person must take responsibility. Each and every one of us who chose those people with our right to vote also share in that responsibility.

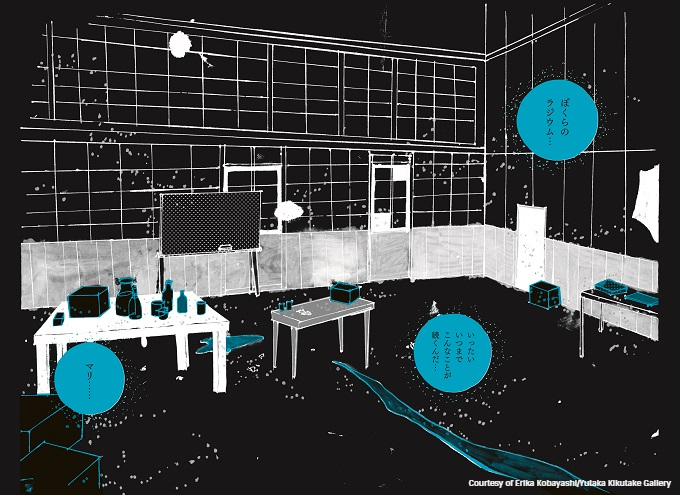

A Study

A StudyIshikawa District, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan.

This is one of the sites related to the so-called "Ni-Go Project", a program by the Imperial Japanese Army and the Rikagaku Kenkyujo (now Riken) to develop an atomic bomb.

His Last Bow, Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix, London, 2019.

Photo by: Alex Christie

- ──Do you mean that in the face of unacceptable facts, your pursuit of the causes inspires you to create?

- After the earthquake, I was very uncomfortable with the way that the dialog was too polarized as to whether nuclear power or radiation was good or bad. When I released Child of Light and Breakfast with Madame Curie, many people pressed me to pick a side, asking, "So, are you for or against nuclear power?" To be honest, I want both people for and against nuclear power to read my works. I believe it is important to learn about history irrespective of your position, and I want to write about things in my work that cannot be conveniently categorized into for and against or good and bad.

For example, Marie Curie was fascinated by beauty of the phosphorescence emitted by radioactive substances. There was one episode where Curie was so captivated by the beauty of radium when she first extracted it, she called it a fairy light and put it by her pillow when she slept. But ultimately she herself would die of radiation sickness.

So if you only talk about the horror or usefulness of radioactive substances and leave out the parts that go beyond reason and fascinate people, then I feel we will just keep repeating the same things over and over again.

We must not forget that it is human nature to seek light and beauty.

So I want to depict in my work the struggle of whether to hold on to it or let it go, and how to come to terms with that, while including those other factors.

Child of Light 1 (Little More)

Child of Light 1 (Little More)- ──It is true that your works take a stance of simply observing people without denial or condemnation.

- One of my most favorite authors is Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich. Her works, based on written accounts and interviews, are nonfiction but succeed in telling a story, such as Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster.

In the Japanese translation of Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets (Iwanami Shoten, Translated by Matsumoto Taeko), she wrote the words, "I am a historian who observes with dispassion, not one who holds a flaming torch. Let the times be the judge. The times are fair, but not times close to us. Rather they are distant times after we are gone. They are times for which we have no attachment." When I read those words, I realized that is also what I was seeking. My job is not to judge, but to record. I felt that this was something I always wanted to remember dearly.

Perhaps it is easier to convey something when you write in a way to judge or agitate, and perhaps the reader is easily satisfied with that. But I have the strong desire to simply write down the moment, the times, objectively, away from that sentiment.

- ──Most of your works take the form of the narrative, but a narrative usually leads up to some sort of emotion. So why did you choose a format that seems to be unsuited for your desire to simply record without judgment?

- I honestly don't know myself (laughs). I guess I just really like stories.

I decided I wanted to be a writer when I read The Diary of Anne Frank as a child, so I happen to believe that the diary is a form of literature. You could say that in my mind, everything is literature and everything is a story. I don't really make a distinction between fiction and nonfiction, or between novels,manga and installation . I believe that the origin of the way I approach stories, diaries, and installations equally without regard to format is the same sense that Anne must have had as she wrote in her diary and decorated the walls of her secret room with pictures and postcards she had drawn. I always want to select the medium that will help me look inside myself with the most honesty. When I do that, I don't think it really matters what the specific medium is.

- ── What kindles your desire to start creating? Is it something that happens to you, or do you nurture an idea you wish to write about as you research one of your interests?

- The thing I spend the most time on when writing a novel is research, whether searching through records or actually visiting relevant places, so I guess I am the nurturing type. I just keep researching anything that captures my interest. In the end, Child of Light and my other works only emerged after nearly ten years of research.

- ──You have repeatedly based stories on the discovery of radioactive substances and on the nuclear accident, although you were not there when those things happened. What is your feeling, as someone who was not involved, on creating a story based on those events?

- That is something I still think about today.

At first, I wondered what I could possibly write about or understand considering that I was not involved or there. But on the other hand, from the standpoint of a foreign country, I am seen to have been involved (in the nuclear accident), and the question remains where one draws a line. So I wavered back and forth between those two opinions.

But then something happened last year that gave me encouragement. That was when Trinity, Tirinity, Trinity was selected for the Tekken Heterotopia Literary Prize.. The other two works selected at the time were Aitakute Kikitakute Tabi ni Deru (I Travel to See and Hear You) by Ono Kazuko (PUMPQUAKES) and Awai Yuku Koro Rikuzentakata, Saigai go wo Ikiru (RIkuzentakata, Life after the Earthquake) by Seo Natsumi (Shobunsha). In both cases, the authors define themselves as outsiders, yet they listen very closely to the smallest voices in order to tell their stories.

Ono Kazuko has spent fifty years visiting the villages of the Tohoku region to collect folk tales. So I was very inspired by her stance of listening and writing down those stories as she walked, even as she faced uncertainty.

Since then, I have decided to do the same by facing the events that occur, considering how to tell the stories of those events, and considering how to pass those stories on to the people of the present and future.

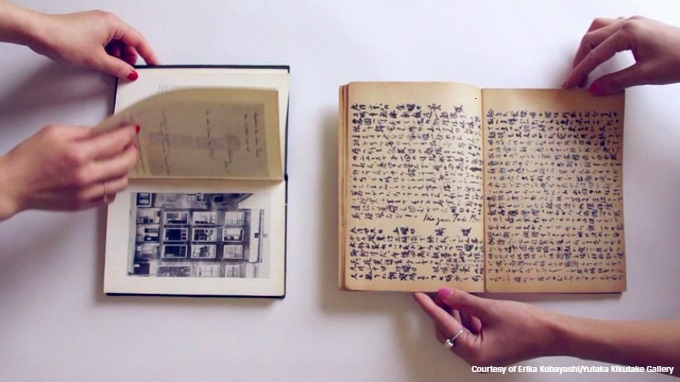

The starting point of my works is the wonder at why I am living through a given situation at the present time and place, so I can only create works from my own perspective. Your Dear Kitty is a work in which I follow in the steps of Anne Frank equipped with her diary and the diary of my father, who was born in the same year as Anne, that he wrote during and after the war at the age of sixteen and seventeen.

I discovered my father's diary when I was visiting my home to celebrate his eightieth birthday, and for the first time, I realized that if Anne Frank had still been alive, she would have been eighty as well. I had always imagined Anne as a teenage girl, but at the time I was beset by a strong desire to read the words of Anne as a middle aged or old woman.

Also, I thought I had known everything there was to know about my father because I had grown up with him. But the sixteen-year-old boy who wrote in his diary the words, "I have survived another day," was an aspect of him with which I was completely unfamiliar, because he had never really spoken of the war to me. And that was the first time I realized that no matter how familiar you are with someone, there are things you cannot know or speak of. But that is not necessarily something to be despondent over. Rather, given that fact, I decided I wanted to discover through creating my works just how much I could know or imagine about the other precisely because I could not understand or know certain things about them.

Your Dear Kitty, 2 Diaries, 2011

Your Dear Kitty, 2 Diaries, 2011The Diary of Anne Frank 1942-1944, My Father's Diary 1945-1946

video 6 min. 48 sec.

- ──So that is the task of reaching out to the unseen things within the other person, isn't it?

- If you think about it, it should be obvious that there are things you don't know about someone no matter how familiar you are with them. But in order to approach that part of them, it depends entirely on how carefully you research the writings and documents that remain, and the history of the past. That is why I always want to do my research as carefully as possible.

- ──In the process of doing research, do you ever have the sense that you are allowing yourself to be someone as you grow closer to them?

- No. My fundamental assumption is that I cannot understand everything about other people, so I believe it is very important to consciously keep that assumption in mind.

Surely you would be able to write much more if you felt you knew everything there is to know about them, but instead I would prefer not to forget the stance that I don't know. I believe I have always taken on the challenge of seeing what I could write given that basic premise.

- ──That stance of never forgetting that you don't know is quite honest.

- That feeling is the same not only for the minds of other people, but for other things as well. Perhaps people often give up or stop thinking when they find they don't know.

The issue of radiation in particular is very complex and difficult, so people often shut their mouths on the subject because they don't know and might be mistaken. But you have to remember that it's impossible to know everything. And furthermore, even if you don't know everything, everyone has the right to try to know, and everyone has the right to speak about their opinions and ideas.

So I wrote Child of Light so that it might be of some help to those who wanted to learn and speak about it.

- ──After what you have spoken of so far, I get the sense that See You on the Bombing Day, which you released long before the works after 2010 in which your theme became clear, is also a work that touches on what it means to be a party to an event in a way that draws the sense of not knowing to you almost physically.

- While I was somewhat in the dark about why I created that work at the time, when I look back on it now, I am surprised to see that I have always been interested in that same theme. How can we take the pain, suffering, or death of some person in the distant past and make it our own? And how can a person who was not party to it convey it to others as an experience? While there are no answers to those questions, they are things that I always wish to know. And I think that is precisely why I continue creating works.

- ──Given the way that the reality of the extreme events today is continually exceeding any fiction, do you believe that the roles played by stories and writers will change in any way?

- It really seems as though reality itself has become some kind of joke, hasn't it? The most absurd things are occurring that I would never be able to come up with as a writer, such as the government considering, with complete sincerity, handing out meat coupons to those who catch Covid-19.

But if you reflect back on history, you see that there was always nothing but absurd things occurring in every era. The story I mentioned a moment ago of Marie Curie placing radium besideher pillow seems far from reality, and when I research the war, I uncover a ceaseless procession of absurd occurrences. So it may be the case that authors must simply continue to write their stories in the midst of absurdity without identifying the present as being particularly special.

There is a line in Sherlock Holmes, one of my favorites, that says, "Life is infinitely stranger than anything which the mind of man could invent." And it goes on to talk about, with sarcasm, knowing the ending to a story beforehand, saying, "It would make all fiction with its conventionalities and foreseen conclusions most stale and unprofitable." So it was true in the 19th century when the Sherlock Holmes stories were written, so I feel that the job of the writer is to keep writing without becoming disappointed when reality outdoes fiction in any era.

- ──What do you think stories will be like hundreds of years in the future?

- What? That's something I'd like to know actually (laughs).

Here is another anecdote about Marie Curie. I once had the chance to look at her actual experimental notes at the library of Meisei University. Her notebook is just an apparently normal looking cloth bound volume, but if you hold a Dosimeter up to it, it still reads high radiation. She was handling radium and polonium with her bare hands, and they told me that even today her fingerprints still emit strong radiation.

The half-life of radium 226 is said to be 1,601 years, so if she touched that notebook in 1902, then the half-life won't be reached until the year 3305. If you count a generation as 30 years, then that's a time when the children living then will be 53 generations in the future. By that time the very name Marie Curie may even have been forgotten, but when I consider that her fingerprints will remain, I am overcome with a both terrible and deeply moving feeling.

Some vestiges will remain for a very long time, and someone might find them.

That simple fact gives me hope.

Just as we today can read The Diary of Izumi Shikibu that was written exactly a thousand years ago, someone a thousand years in the future may find some vestiges that we leave behind.

While I do not know the future of stories, I am constantly reminded that some vestiges will be left behind a hundred or thousand years into the future.

"Image Narratives: Literature in Japanese Contemporary Art", She waited, U234 and U235 at Kiel, In My Hand - The Fire of Prometheus, 2019, The National Art Center, Tokyo, Installation View

"Image Narratives: Literature in Japanese Contemporary Art", She waited, U234 and U235 at Kiel, In My Hand - The Fire of Prometheus, 2019, The National Art Center, Tokyo, Installation ViewPhoto: Nakagawa Shu

- ──Do you create works now in order to leave a footprint behind?

- When I was a child, I was very much afraid of the idea of dying without leaving anything behind. Even more so than the desire to leave something behind or the fear of death, I had a strong desire to become a writer as soon as possible and leave behind works out of the wish to leave some sign that I had lived.

I put great effort into writing when I grew up and actually became a writer, but then one day I realized the obvious fact that no matter how hard I write, I cannot write everything. Not only is it impossible to record everything and leave a record of it, but in fact the number of precious moments for me that pass by without ever being written down are far greater.

When I am researching history and records, I often encounter events that are only mentioned in a single sentence, or people and incidents the names of which were not even recorded.

But I no longer assume that they were unimportant because they were not written down.

Since then, I have wanted to search for the traces of people and incidents that were left unwritten, and to write about the lives of those people and those incidents.

When I imagine what the daily lives of each of those people must have been like, the story begins to emerge within me. To discover between the lines of historic records the moments that might have been precious and valuable to those who died without leaving anything behind is what drives me to write these days.

- ──Is there the sense that you have shifted from leaving your own footprint to leaving a footprint for someone else?

- Just as I do my best to record some traces of the past, someone in the future may find something about me, as an individual, or about all of us alive today. To me that idea is full of hope.

- ──I get the sense that future appears in your works as something that everyone has the responsibility to choose for themselves.

- When I traced Anne Frank's steps for Your Dear Kitty, I followed an itinerary of starting at the place she died and moving towards the place she was born. When I first visited the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen where she died, I thought to myself, "If this place had been liberated only one month earlier, Anne would not have had to die."

I then traveled to Auschwitz and on to the safe house where she had lived in Amsterdam. When I arrived, I thought to myself, "If this place had remained a secret for just a few more days, Anne would not have died."

Finally, when I arrived at the home where she was born in Frankfurt, it occurred to me that if nobody had voted for the Nazi Party in Germany, Anne would not have died. For the first time, I had a strong sense of the fact that the choices of individuals can decide whether someone in the future lives or dies. I realized that this also meant that my choices now could save or kill someone in the future.

- ──Are you ever discouraged by the fact that so many lessons of the past are not being applied today?

- As I look back on history while writing my manga, there are often scenes where I can't help but say to myself, "Wait!" There are many crossroads where, looking back from the future, I want to say, "If only they did this, or that." But at the same time, I am also faced with the frustration that I myself cannot prevent or resist those situations against the immense flow of time. And it frightens me when I realize that there may have been people who felt the same as they were caught up in that flow and became swept away during those many crossroads in history.

But rather than giving up, I intend to keep pushing forward. In the end, it is important to be aware of just how much responsibility we have for our choices. Even if the outcomes of those choices are disappointing, that awareness completely changes how much regret we feel.

For that reason, I hope to always retain the perspective of looking back on the past, whether 10 or 20 years in the future. Everyone is busy now, myself included, and our hands are full just taking care of ourselves, so we often want to prioritize the most immediate benefit. But what effect will that choice have on ourselves or others in the future? I hope, through my works, to continue creating opportunities to consider that together.

My Torch, 2019, C-print 54.9×36.7cm (each, set of 47)

My Torch, 2019, C-print 54.9×36.7cm (each, set of 47)Photo: Nogawa Kasane

- *¹ See You on the Bombing Day was a project that started on the day that the aerial bombardment campaign began in Afghanistan, one month after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York, in which Kobayashi stayed at the house of an acquaintance starting that night and kept a diary of the dreams she saw. The work is a record of the 133 days during which she recorded her daily activities in detail while reporting the places that were bombed and the number of lives lost to the owner of the house.

Online interview, June 2021

Interview and text by Miyoshi Gohei (Sanseisha)

All photos courtesy of the artist.

Courtesy of Kobayashi Erika/Yutaka Kikutake Gallery

Related Articles

Back Issues

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…