Judo exchanges fostered by the JAPAN-ASEAN JITA-KYOEI PROJECT

2019.11.19

【070: Japan & Southeast Asia: Building Bonds through Sports】

Judo is a martial art known throughout the world. One of the mottoes of Kano Jigoro Shihan (Master), the founder of judo, is jita-kyoei, often translated into English as "mutual welfare and benefit." In line with Kano Shihan's belief that "each of us prospers together with others when we trust each other and help each other," the Japan Foundation Asia Center and the Kodokan Judo Institute* are jointly running the JAPAN-ASEAN JITA-KYOEI PROJECT. By developing higher-level leaders and making education more broadly available to a wide range of participants including athletes, coaches, and referees, the project is building a network between Japan and ASEAN countries and promoting mutual understanding among participants.

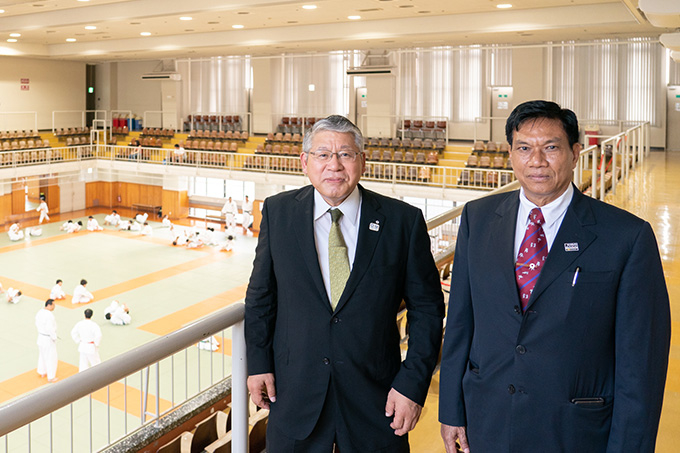

The Japan Foundation has been dispatching judo instructors for many years. As a result of this and other activities, judo has been taught in Southeast Asian and other countries for about 40 years. In Myanmar, Mr. Shinro Fujita was named Honorary Patron of the Myanmar Judo Federation and is even called "the father of Myanmar judo," while the president of the federation, Mr. Tun Tun, works hard to increase the knowledge and practice of judo in the country. We spoke with both of these individuals, who are involved in the JAPAN-ASEAN JITA-KYOEI PROJECT, about the popularization of judo outside Japan and about prospects for the future.

From left: Mr. Fujita and Mr. Tun Tun

──Mr. Fujita, what inspired you to start teaching judo outside Japan?

Fujita: One of my college classmates did it first, going to Austria to teach judo. In those days, unlike today, opportunities to go overseas didn't come along very often. So I took a job in a private company, but I couldn't completely give up my dream of teaching judo outside Japan. When I was 27 years old, I took a course at Kodokan and urged them to send me overseas. As a result, from January 1978 I was able to go to Bangladesh as a judo instructor for one year as part of the Japan Foundation's judo instructor dispatch program. It was the first time in my life that I left Japan. Bangladesh was still a very young country. Information about that part of Asia was limited in Japan, and very few people traveled there. After my return, I spent more than a month from November 1979 traveling around five countries in Southwest Asia as well as Thailand as part of a teaching delegation. One of the four members of the delegation was the Munich Olympic gold medalist Toyokazu Nomura (uncle of Tadahiro Nomura, who won gold medals at three consecutive Olympic games).

The duration of our stay was mostly four or five days per country, so I felt extremely fortunate that I was able to go to Bangladesh for a whole year and teach on an ongoing basis, rather than just demonstrating some waza (techniques) and leaving.

──How was your experience of teaching overseas?

Fujita: I made various mistakes and learned through trial and error. When I was in Bangladesh, maybe because I had the honor of representing Japanese judo, I thought that I should have been shown more respect. As a result of that arrogance, I felt frustrated most of the time. After my return to Japan, the Kodokan teachers gave me some good advice, and I learned from books and other sources that the Japanese way of thinking is different from that of non-Japanese people.

From 1980, I started making frequent short trips to Myanmar. Whereas in Bangladesh I used to get angry and exclaim, "They should be able to do it!" "They aren't trying!" "They aren't listening!" in Myanmar I switched my exclamations to questions and began to seriously inquire, "Why can't they do it?" "Why don't they do it like this?" "Is there some reason for the way it is?" As soon as I changed my approach, the world began to look completely different. When I interacted with the athletes, I also started using a question-and-answer format, for example, asking, "Do you want to become more proficient?" Rather than just commanding, "Do this!" I began to gain the understanding of each student before giving instruction. I began to explain, "If you want to improve, you will have to conduct your training differently from how you have been practicing so far, and you'll also have to practice like this, okay?" At that time there were not enough different kinds of training available in Myanmar, so I taught various methods that would allow them to compete elsewhere in the world. I began to carefully explain fundamental ideas like why techniques are applied as they are, and why the basics are so important.

In time, the locals were saying, "Mr. Fujita understands the mentality of Myanmar people, so we would really like to have him come teach us," and from August 1985 it was decided that I would go teach there for one year.

──Do you think that you and Myanmar are particularly suited for each other?

Fujita: I have an intuitive attraction to the place. Partly because the people are friendly and partly because when they do something, they do it with everything they've got. When I first went, I was uncomfortable with the social systems because they were very different from what I was used to, but the people were basically good in nature. I had already experienced inconveniences and culture shock in daily life in Bangladesh, so Myanmar was not so hard for me in those respects. I enjoyed meeting and teaching my students every day so much that I taught for three hours each morning and afternoon, although people said there was no need to practice so much. In Japan, most places do not even practice three hours a day.

──Mr. Tun Tun, when did you first meet Mr. Fujita?

Tun Tun: I first met him in May 2006 when I became president of the federation and went to Kodokan to pay my respects.

Fujita: Since then, we have met too many times to count. Once Mr. Tun Tun became president, I began to receive exceptional hospitality whenever I visited Myanmar. Especially this February, when I visited as an officer of a training team from the Hokushin'etsu University Judo Federation, I was surprised to be treated like an important VIP: Everywhere we went we were preceded by a motorcycle police escort.

──Is judo popular in Myanmar?

Tun Tun: It is quite well known. Japanese martial arts such as judo, kendo, and karate were introduced from Japan to Myanmar before World War II. It was first taken up by the military and then spread to the private sector. There are almost no club activities in schools, so I would like to popularize it in the educational field.

Following the uprising and government crackdown that occurred in Myanmar in 1988, activities by university students were not allowed. So it was a major accomplishment when the Myanmar Judo Federation held a university judo competition this year for the first time in over 30 years. Currently, we are also arranging opportunities for exchange with Japanese university judoists.

──How do you feel about Mr. Fujita's guidance?

Tun Tun: We are very grateful.

Fujita: Many young instructors were dispatched after me. They have all been people of good character who have worked very hard while maintaining good communication with athletes and coaches. I am extremely proud that they have built a good reputation for Japanese judo instructors.

──Are there also advantages for the Japanese judoists who come to Myanmar to teach judo?

Fujita: Teaching is a great way to learn. At Kodokan, we cultivate a strong awareness of the idea that "an instructor who forgets to learn is no longer an instructor." I always tell people who are going out to teach: "When you get to your destination, don't just rely on your knowledge and past experience. Keep learning!" "Don't hold back knowledge and techniques when you teach," and, "I want you to become a bridge between countries through judo." At the end of the day, we want people outside of Japan to experience the joys of practicing judo.

JAPAN-ASEAN JITA-KYOEI PROJECT visit to Myanmar in 2017 (photo provided by Mr. Fujita)

──Why do you suppose so much emphasis has been placed on spreading judo overseas since the days of Kano Jigoro Shihan?

Fujita: Kano Shihan lived after the time of Japan's cultural enlightenment, so Japan was learning many things from Western countries. It then seemed to be Japan's turn to give back to other countries through cultural exchanges in the spirit of jita-kyoei, and the idea was that judo was something Japan could contribute. Kano Shihan personally performed demonstrations while explaining the virtues of judo in English and German. He selected the best instructors from among his disciples and sent them abroad. Among those disciples were a married couple, Yoshitsugu and Fudeko Yamashita, who introduced judo to then-U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt and made it popular among elite American women.

The best thing about judo is that it allows people to overcome language barriers through direct physical contact, and judo itself serves as a common language between people of different nationalities. The fact that people can come up with solutions to problems after struggling together can be applied not only in the world of judo, but also to society as a whole. I think that lessons like these have truly become more widely known.

──The two of you have been involved in this project since its inception. What is your view of the project's accomplishments?

Fujita: First, we conducted a survey to identify needs and found that human resources development was crucial. Japan took the lead in repeatedly dispatching instructors and inviting coaches to Japan from overseas. As a result, human resources have been rapidly developed. Former students are now part of a "judo family" who see themselves as brothers and sisters. As I see it, all of those "family members" are lifelong assets.

Also, regarding our goal of building networks, now that there are social networking services, exchange has become more active. For example, there is talk of people going from Singapore to Myanmar for joint practice sessions.

One more major achievement was the establishment of a judo federation in Brunei, which had been the only ASEAN country without one, allowing Brunei to join the International Judo Federation. There had been instructors in Brunei but no organization. Without support from the JITA-KYOEI project, it might have taken Brunei decades longer to join the federation. Neighboring countries are also happy about this development.

Tun Tun: I really think "mutual welfare and benefit" is a wonderful phrase. In Myanmar as well, if many people develop an interest in judo thanks to this project, it may provide an alternative to drugs and other social problems and provide some relief from the horrors of war.

──The Tokyo 2020 Olympics are coming up soon. What are the Myanmar judo community's goals for the future?

Tun Tun: First of all, we will train harder in preparation for the Southeast Asian Games scheduled for December. Participating in the World Judo Championships held in Tokyo in August is our first step toward competing in the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. I plan to take advice from Mr. Fujita as we work toward being able to participate in the Olympics.

Fujita: In addition, I would like you to strengthen from competing at the Southeast Asian level to the Asian level as your next step. It is also important to cultivate internationally active referees and people who have the necessary skills to manage tournaments. I would like you to expand your horizons through international exchanges with Japanese university students and judo practitioners from other countries. I hope that we will continue to work together as good partners to cultivate human resources and to quickly expand the world of judo to Myanmar, ASEAN countries, Asia, and the rest of the world.

At Kodokan, in front of the statue of Kano Jigoro Shihan

Inside Kodokan, viewing a new exhibit of judoists who are active overseas

Shinro Fujita

Born in 1950. Kodokan Judo 8th Dan. Kodokan instructor, Councilor of the All Japan Judo Federation, Honorary Patron of the Myanmar Judo Federation, Technical advisor of the Singapore Judo Federation. Among other positions, he has served as the director of the Kodokan international department, chairman of the All Japan Judo Federation international committee, Special member of the Kata Committee, Member (for the women's division) of the National Team Committee, and Kata Commission member of the Judo Union of Asia.

Through the Japan Foundation's overseas judo instruction program, Mr. Fujita taught in Bangladesh from January 1978 to January 1979, in Myanmar from August 1985 to August 1986, and in Jordan from December 1986 to January 1987.

Tun Tun

Born in 1955. In 2006, he became president of the Myanmar Judo Federation and took responsibility for teaching and promulgating judo throughout Myanmar. In 2016, he participated in the JAPAN-ASEAN JITA-KYOEI PROJECT that was inaugurated in Japan. The Myanmar Judo Federation won four gold medals at the 2013 Southeast Asian Games.

*The Kodokan Judo Institute

Founded by Kano Jigoro Shihan in 1882, it is the headquarters of Kodokan Judo, the most popular school of Judo that is practiced in over 200 countries and regions worldwide. Kodokan carries out an array of initiatives such as running Kodokan, a Judo school for youths; holding conferences and study groups lead by Judo instructors on the training and health of youths, organizing international as well as domestic competitions, bringing up Judo instructors, sending Japanese instructors overseas as well as welcoming foreign instructors, and managing the dan examinations.

August 2019 in Tokyo

Interview / text: Hitomi Terae (Japan Foundation Communication Center)

Photos: Hajime Kato

Related Events

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…