In the Real World - Japan Pavilion at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale

Thomas Daniell (Head of the Department of Architecture and Design, University of Saint Joseph, Macau)

The Japan Foundation participates in the International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale every time to organize the Japan Pavilion. In 2014, we appointed Ms. Kayoko Ota as the Commissioner and set up the Japan Pavilion with "In the Real World: A Storehouse of Contemporary Architecture" as the pavilion's theme for the 14th edition of the exhibition.

In this article, Prof. Thomas Daniell who visited the Japan Pavilion on the opening day talks about the pavilion reflecting on the history of architecture.

Japan Pavilion ©PEPPE MAISTO

From the 1960's to 70's: Approach to the Real World

With its provocative title 'In the Real World' (as opposed to what - fake? imaginary? ideal? surreal?), the Japan Pavilion's focus on the architectural research and design of the 1970s makes a counterbalance to the attention given in recent years to the 1960s, a decade dominated by the Metabolist movement (an architectural movement led by a group of young Japanese architects and urban planners including Kisho Kurokawa, Kiyonori Kikutake and Fumihiko Maki who were greatly influenced by Kenzo Tange. This word is based on the biological term "Metabolism"). Indeed, within the historical trajectory of Japanese architecture, the 1960s and 1970s are practically polar opposites. The reasons for this are partly economic (postwar economic growth had turned Japan into the world's second richest country by 1968, then the 1973 oil crisis triggered a national recession) but the effects were ideological. Whereas the 1960s was a period of totalizing urban visions predicated on the need to rebuild Japan's war-devastated cities and the availability of seemingly unlimited resources to do so, the economic downturn of the 1970s, exacerbated by escalating environmental damage and grassroots political protests, split the Japanese architectural world's formerly unified sense of mission into innumerable personal obsessions.

The point of inflection occurred in 1970, at the Osaka Expo. Apotheosis and swansong of Metabolism, the Expo was a magnificent success on every level except one: it was fatal to the public perception of Metabolism as a viable model for the future of Japanese cities. Invited by the Japanese government to address the real, urgent needs of urban reconstruction and population growth, the Metabolists had proposed radically new types of cities projected into the air or across the sea. The designs were often sublime and occasionally picturesque in their artful compositions of clustered capsules, spreading infrastructural trees, amoeboid platforms, and so on. But they were rarely light on their feet, more often sluggish juggernauts negotiating their territory with a brontosaurian stomp-and-growl. Like tiny mammals hiding in the undergrowth, the younger architects who would come to prominence in the 1970s were watching and waiting, intuitively aware that this era of gigantism was coming to an end. Among the general public as well as architects, the Osaka Expo triggered a backlash against megalomaniacal utopianism in favor of themes that were more humble, mundane, pragmatic, and plausible - approaches to architecture and the city that indeed might be described as being in the real world.

To a large extent, these new attitudes were given theoretical grounding by the work of the two most influential architects of the period: Kazuo Shinohara, who had spent the 1960s in outspoken opposition to the Metabolists, and Arata Isozaki, an early associate of the Metabolists who became increasingly critical of their ambitions. In concrete terms, this was a shift from envisioning radically systematized urban plans to creating introverted private houses, from the imitation of the language of Western modernism to the study of non-Western vernaculars, from the ruthless demolition of historical urban fabric to the collection and documentation of overlooked buildings and objects, from rigid authorial control of cities and buildings to user participation in the design process, from industrialized prefabrication to ad hoc self-build projects, from strident manifestos to a proliferation of iconoclastic 'alternative' publications, from the rationalization of society and industry to the celebration of difference and idiosyncrasy.

Photos: @Takeshi Yamagishi

By courtesy of the Japan Foundation

Japan Pavilion Which Looks to Be a Museum

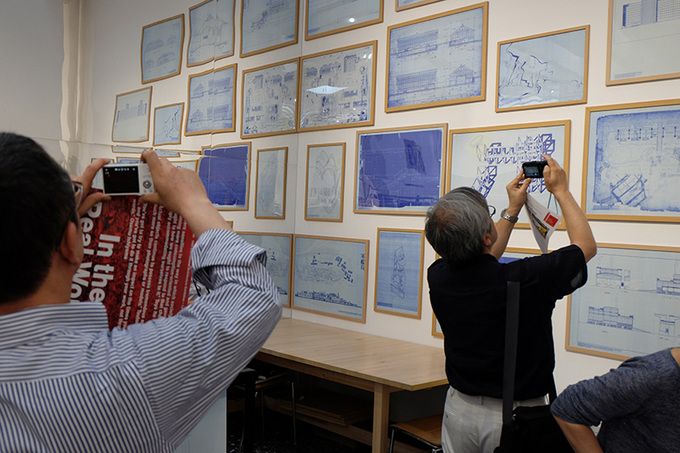

For this biennale, the Japan Pavilion has been reconfigured as a warehouse full of wooden crates, like an archive in the process of being exhumed. Much of the work on display was initiated in an attempt to document or salvage traces of Japan's architectural and urban history, a belated response to the collateral damage of postwar modernization - serious environmental pollution in the countryside, thoughtless destruction of ancient and recent past in the cities. Included here is Tsuguo Aizawa's field survey of a well-maintained rural village, begun in 1969 and ultimately leading directly to government legislation for historical preservation. Other exhibits range from physical building fragments to the more ephemeral phenomena that can only be captured in photographs and sketchbooks: Takashi Hasegawa's documentation of the Expressionist architecture from the Taisho era (1912-26), surveys of 'lost' modern architecture in Tokyo by Terunobu Fujimori and Takeyoshi Hori's Architectural Detective Agency, samples from Tsutomu Ichiki's collection of evocative objects rescued from demolished buildings, Genpei Akasegawa's photographs of the mystifying artifacts he calls 'Thomassons', and examples of Tomoharu Makabe's 'urban frottage' (graphite-on-paper rubbings of building and street surfaces). Makabe was a founding member of the Lost Items Research Institute, a group of architecture students who, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, used discarded objects as 'clues' from which to deduce patterns of urban behaviors. Fascinated by the empirical reality of the city around them, the Lost Items Research Institute was, like almost all the observers and collectors gathered here, inspired by the early-twentieth-century work of Wajiro Kon, an architecture professor at Waseda University who invented a discipline he called 'modernology' in order to document the behaviors and living environments of a rapidly modernizing Japanese society. Kon's surveys of the rough shelters built by survivors of the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake soon diverged into various unusual themes, few of them directly architectural. Nonetheless, the techniques of recording and diagramming developed by Kon and his colleagues have inspired documentary fieldwork by every generation of Japanese architects since then.

Photos: @Takeshi Yamagishi

By courtesy of the Japan Foundation

Surveys of vernacular building typologies and settlement patterns in Japan and elsewhere also provided architects with hints for avoiding Western, modernist influences in their designs. Kazuo Shinohara's studies of traditional dwellings, undertaken with the help of his student assistant Kazunari Sakamoto, led to the uncompromising experiments of his House with an Earthen Floor (1963) and House in White (1966), presented here as precursors to the hermetic urban retreats of the 1970s such as Toyo Ito's White U and Tadao Ando's Row House in Sumiyoshi (both 1976). The emphasis was on innovative spatial effects rather than conventional domestic comfort, as epitomized by Monta Mozuna's Anti-Dwelling Box (1972). Hiroshi Hara, an associate professor at Tokyo University at that time and professor emeritus at the present time, also spent the 1970s touring and analyzing village typologies around the world together with groups of his graduate students. This influenced Hara's early house designs, represented here by the Reflective House (1974), as well as the Yamakawa Cottage (1977) by his former student Riken Yamamoto. Hara was later able to incorporate ideas extracted from the village research in large-scale architectural projects such as the Umeda Sky Building (1993), the most recent project included in the exhibition.

In 1970, Sekisuiheim launched the Sekisui Heim M1 prefabricated modular house, designed by Katsuhiko Ohno. Thousands were sold, many to architects who modified them to fit their own preferences - if the Metabolist emphasis on technological rationalization was widely rejected by the architects of the 1970s, they still understood that industrialized construction methods could not be realistically avoided, only adapted. Osamu Ishiyama also collaborated with Ohno in developing modular prefabrication systems and building components that he sold to others, notably Monta Mozuna and Toyo Ito. Ito's brief interest in industrialized, customizable housing is represented in the exhibition by the House in Umegaoka (1982), using what he called the Dom-ino System in homage to Le Corbusier. Ishiyama and others also became involved in long-term self-build projects for their own residences, exemplified by Eiji Ebihara's Crow Castle (1972) and Isamu Kujirai's Chicken Coop house (1973). User participation in the design and construction of public projects is represented here by the Atelier Zō's Miyashiro Civic Center Shinshukan of Miyashirocho Town (1980).

Photos: @Takeshi Yamagishi

By courtesy of the Japan Foundation

In asking the national pavilions to address the theme 'Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014', biennale commissioner Rem Koolhaas made it clear that he did not intend this to be understood as a gentle process like, say, a sponge being gradually stained by an alien liquid, but closer to the way 'a boxer absorbs a punch'. Leaving aside the contentious distinction between modernity as a condition (the dissolution of traditional social structures) and modernism as a movement (an artistic response to that condition), the national pavilions collectively demonstrate that the initial West-to-East flow of modernization, and its countercurrent of appropriated exotica, has become a constellation comprising nodes of greater or lesser reciprocal influence, the received concepts and techniques of modernism renewed by the idiosyncrasies of each host culture then transmitted elsewhere or reflected back to the source. But few nations have been punched so momentously by modernity as has Japan, from its mid-nineteenth-century forced opening to the world by a delegation of American warships, to the mid-twentieth-century atomic and incendiary bombing campaigns - both events followed by long periods of accelerated modernization and Westernization. Yet no nation has so flexibly absorbed such punches, rolled with them, indeed absorbed and redirected their impact with jujutsu-like skill. The Metabolists adopted the megastructural concepts that were so prominent in the Western architectural discourse and practice of the 1950s, then synthesized them into radically unique proposals throughout the 1960s. The eccentric and iconoclastic Japanese architects of the 1970s searched for alternative sources of inspiration in a wide range of places and times, cumulatively forming an incubator for the protean, pluralistic creativity of today - an alternative evolutionary path for modernism that is unmistakably specific to Japan yet continues to influence architectural culture worldwide.

Thomas Daniell

Thomas Daniell

Currently serves as Head of the Department of Architecture and Design, University of Saint Joseph, Macau. After graduating from the School of Architecture, Victoria University of Wellington, he obtained Master of Engineering at Kyoto University and Ph.D. at RMIT University. He published various books and literature including After the Crash: Architecture in Post-Bubble Japan (2008), Houses and Gardens of Kyoto (2010), etc.

Keywords

- Architecture

- History

- International Exhibition

- Japan

- Italy

- University of Saint Joseph

- Venice Biennale

- International Architecture Exhibition

- Kayoko Ota

- Metabolism

- Kisho Kurokawa

- Kiyonori Kikutake

- Fumihiko Maki

- Kenzo Tange

- oil crisis

- Osaka Expo

- Kazuo Shinohara

- Arata Isozaki

- Tsuguo Aizawa

- Takashi Hasegawa

- Terunobu Fujimori

- Takeyoshi Hori

- Architectural Detective Agency

- Tsutomu Ichiki

- Genpei Akasegawa

- Tomoharu Makabe

- Wajiro Kon

- Lost Items Research Institute

- Waseda University

- modernology

- Kazunari Sakamoto

- Great Kanto Earthquake

- Toyo Ito

- Tadao Ando

- Monta Mozuna

- Tokyo University

- Hiroshi Hara

- Riken Yamamoto

- Katsuhiko Ohno

- Sekisuiheim

- Osamu Ishiyama

- Le Corbusier

- Eiji Ebihara

- Isamu Kujirai

- Atelier Zō

- Rem Koolhaas

- Modernity

- megastructures

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…