Macbeth in Paris

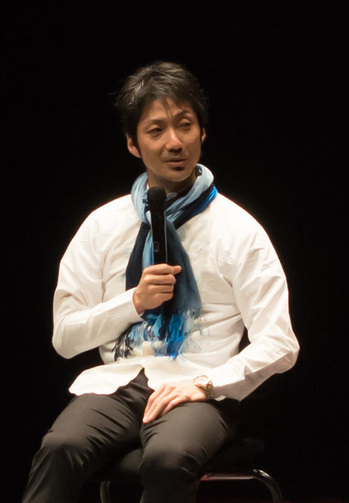

Mansai Nomura (Kyogen actor; Artistic Director, Setagaya Public Theatre)

Since being appointed Artistic Director of Setagaya Public Theatre in 2002, Kyogen actor Mansai Nomura has dedicated himself to producing a number of works by William Shakespeare as stage productions enlivened with a modern touch.

Dramatic reading performances of Macbeth, one of Shakespeare's four great tragedies, began in 2008 and the first fully-staged performance took place in 2010. In 2013, it returned to the stage in four cities - Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul and New York - and in these performances the minimalist production methods of Noh and Kyogen were boldly introduced and led to rave reviews from all quarters. Using just five actors, the story was told in a simple and easy-to-understand manner and the inner anxieties and conflicts the characters harbored were depicted with sensitivity and care.

This year, in 2014, following a performance in Romania, it was performed at Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris and ended with huge success. The following is a talk given by Mansai Nomura after the first day's performance and an interview conducted by a Japan Foundation staff member.

■ Post-performance talk

Moderator:When I spoke to members of the audience, many were familiar with the term Kyogen - those who were unfamiliar with it were the minority. To begin with, could you tell us how the Mansai Nomura version of Macbeth is influenced by Noh and Kyogen?

Nomura::Maybe the fact that it is performed by five people? With the addition of a Noh chorus it could well become Noh, I suppose. Through abbreviation and simplification, the essence is extracted and is shown symbolically. Striking a chord with the audience's capacity for imagination by taking a Scottish tragedy that is by nature a long-running drama and shortening and simplifying it to this extent is in itself a Noh/Kyogen concept. In Noh the central character's tragic nature is shown in order to emphasize that character, to the extent that there is even a special term for it: shite hitori shugi (the concept of one central character). However, this time around a single couple - in the form of the husband and wife - are regarded as the tragic central character and the three witches play all the opposing roles. Kyogen differs from Noh in that there is a comical aspect to observing people from an ironic distance. Take a person who is madly in love, for example. If viewed from a Noh perspective the focus will be that the character is so madly in love it is pitiable. However, seen somewhat ironically from the perspective of a witch, they may well be thinking "What an idiot for falling madly in love with someone like that."

Nomura::Maybe the fact that it is performed by five people? With the addition of a Noh chorus it could well become Noh, I suppose. Through abbreviation and simplification, the essence is extracted and is shown symbolically. Striking a chord with the audience's capacity for imagination by taking a Scottish tragedy that is by nature a long-running drama and shortening and simplifying it to this extent is in itself a Noh/Kyogen concept. In Noh the central character's tragic nature is shown in order to emphasize that character, to the extent that there is even a special term for it: shite hitori shugi (the concept of one central character). However, this time around a single couple - in the form of the husband and wife - are regarded as the tragic central character and the three witches play all the opposing roles. Kyogen differs from Noh in that there is a comical aspect to observing people from an ironic distance. Take a person who is madly in love, for example. If viewed from a Noh perspective the focus will be that the character is so madly in love it is pitiable. However, seen somewhat ironically from the perspective of a witch, they may well be thinking "What an idiot for falling madly in love with someone like that."

What I can say overall is that I started with the phrase "the universe" at the beginning.

Moderator:Is that something you added yourself?

Nomura::Yes, I only came up with the lines in the introduction. A kind of "zooming in" takes place, from cosmic dust down to the dregs of people. Three years ago I performed Kusabira (Mushroom) at Théâtre du Soleil's theater in Bois de Vincennes (on the outskirts of Paris). Kusabira is a work that quite simply employs a Kyogen-type universe in the form of proliferous mushrooms. The story concerns a house constructed on a mountain that has been leveled, in which mushrooms pop up one after the other. The sight of the mushrooms increasing in number every time they are eliminated is very interesting. In this way then, Kyogen contains the concept that "nature is bigger than human beings."

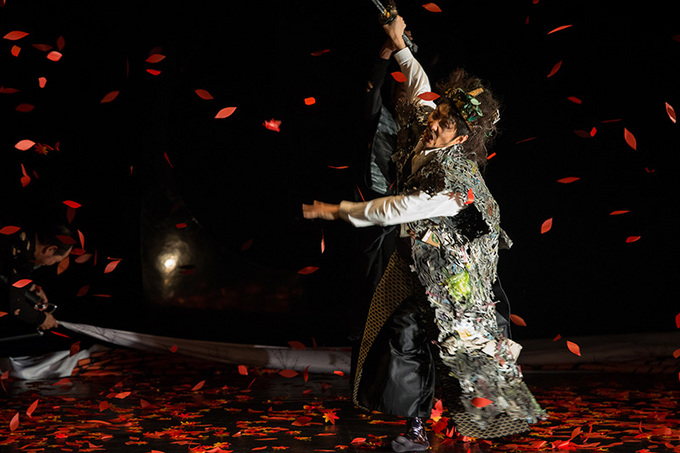

This time around, I positioned the witches as ruling the universe and living alongside the universe, and incorporated the changing of the four seasons into the production. Initially, in the scene where Macbeth is promoted to feudal lord, I expressed it as what might be described in Japanese as the spring of life, and had cherry blossoms fall. When he becomes king it is summer, so cicadas are chirping very loudly, and when the peak of his life passes, autumn leaves are scattered about and the couple's lives begin to gradually wither. Lastly, Macbeth approaches death with the stage covered in snow.

In Japan the color white means "to be purified," and so to have snow fall and be purified suggests that the final salvation of human beings is to be able to return to the soil. Thus the universe is also one person, in fact.

Moderator:As we have just heard, the opening sequence contained your unique analysis. There was a round window on stage also, wasn't there?

Nomura: People who come to this venue frequently may have seen the round window before, but my intention was to leave it up to people's imagination to think that there was a window like that in Japan, and ponder about what its significance is. A window can divide the outside from the inside, but it can also be seen through.

What is a blue circle associated with? To me it conjures up "Earth." It is human nature to harbor aspirations that tomorrow things will probably be better, but simultaneously, if tomorrow is better, then waste is always generated, which will lead to the Earth's destruction.

In Macbeth, the phrase "Fair is foul, and foul is fair" is repeated a number of times. This emphasis on two-sidedness comes about because as lifestyles improve and higher positions are attained, negative elements also naturally come about. Who is fair and who is foul, exactly, witches or people? When that question is asked, from a human-centered perspective, naturally people appear fair, but it is the other way around from a witch's perspective. This two-sided nature of perception is symbolized in the dialogue, and so I created the structure of the witches and the humans.

Moderator:Yesterday I went to see Théâtre du Soleil's Macbeth. 42 people took the stage in that performance, while in your case it was five. What was your impression of their Macbeth?

Nomura:ith 42 performers, as well as the musicians and behind-the-scenes personnel, I was overwhelmed by their scale, which has a huge number of people operating as an entire contingent. To put on a majestic historical drama, those sorts of numbers are needed, and I experienced that intensity.

The number of people involved differed, but I also noticed that the two performances had a lot in common, by which I mean the various ways they employed symbolism. A cloth is spread out and expresses the world view. In Théâtre du Soleil's case this was a gorgeous carpet but we just used two cloths that resembled traditional Japanese wrapping cloths, furoshiki (laughs). The fact that one space can be created within that is without a doubt due to the symbolic nature of Noh. Rose petals were scattered about to symbolize blood.

think it would be good to watch Théâtre du Soleil and become fully familiar with Macbeth before encountering the symbolism of Noh. Likewise when you watch classical Noh it is a cardinal rule to know a certain amount about The Tale of Genji and The Tale of the Heike. Without that prior knowledge the narratives are only conveyed partially and symbolically, and it is difficult to try to use them to study history.

■ Interview

- I assume you have had a chance to talk to the local audience, but could you tell me what the response has been after the first day?

Nomura:Last year I also performed the play in Seoul and New York, so I had a feeling we would probably enjoy a degree of appreciation, but because this is the first time I have performed Macbeth in Europe I felt a mixture of expectation and uncertainty about how it would be received. In Seoul we were able to perform with the same sort of feeling as in Japan. In New York, the audience appreciated the presence of the witches as a type of comic relief (humorous characters, scenes or dialogue that appear during serious stories to ease the tension), and roared with laughter.

In Europe, I had the feeling the audience was observing seriously and concentrating. They stayed alert and held their breath while watching the scenes unfold, which gave us a sense of fulfillment.

You could probably describe it by saying that if the New York audience watched in a Kyogen-like way then in Paris the audience watched in a Noh-like way.

- Was there a difference in the audience reaction in Sibiu (Romania) and Paris?

Nomura:In Sibiu there was overwhelming surprise at the fact Shakespeare would be performed in a Noh and Kyogen style. I performed classical Noh there long ago when Russia was part of the Soviet Union. The audience initially seemed to undergo a culture shock of seeing something they had clearly not witnessed before. They were very quiet and I got a sense they were able to feel elements of familiarity with culture and respect for the venue in a very serene manner.

- In the play Macbeth, the witches predict fate and end up putting the lives of several people off course, and by rights they should be an evil presence, but in your Macbeth, while there is no question they are evil, at the same time they also possess humorous or human traits, and I felt they resembled the characters who play the villains in Kyogen. You have made quite a unique interpretation of Shakespeare's Macbeth, haven't you?

Nomura:When you watch various interpretations of Macbeth, generally the witches are a little spooky and reflect human truths. Although there is modern analysis suggesting that the witches assert what Macbeth himself is thinking, perhaps because my field is medieval entertainment I saw it as the amusing nature of deceit.

- Macbeth and his wife are deceived rather than being killed directly. And Macbeth himself follows a path that leads to ruin.

Nomura: It may well be that within me I leaned toward performing Richard III and then Macbeth. Shakespeare is said to have written Richard III and then written Macbeth after that. Richard III is himself a villain and so when he appears the audience becomes complicit, and I think there is enjoyment in having him represent the evil that humans possess.

I present a similar effect to this with the witches, not with Macbeth. I think this reversed behavior is summed up by the words "Fair is foul, and foul is fair." Macbeth makes the witches speak these highly symbolic words. What appears fair is foul, and what appears foul is fair, it depends on where the observation point is placed in terms of which side you are looking from. Conceivably, a witch appears to be foul and wicked when looked at from a human's perspective. When looked at from a witch's perspective undoubtedly it is the humans who appear the foul ones.

In some respects the witches may well be a presence that has been banished from human society and escaped to the forest, but this time, I had a sense of wanting to show them as human beings and put them on an equal footing: take people who seem to be born from the dregs and sleeping with the dregs, a sort of homeless people if you like, and contrast them with a man who appears to be riding a wave of success, and ask which side is happy and which side is in fact pursuing humanness.

Depending on whether the point of view is Noh or Kyogen, Kyogen involves doing the tricking while Noh involves being tricked. Because I am involved in Noh and Kyogen I adopt both perspectives and exercise an even-handed judgment. I make it so that either perspective can be seen. That is what I intended to achieve.

- You have taken on a large number of Shakespeare's works, including Kuninusubito (The Usurper), which was based on Richard III, Horazamurai (The Braggart Samurai) and Machigai no Kyogen (The Kyogen of Errors). Is there a reason or emotional attachment behind your frequent involvement with works by Shakespeare?

Nomura:I was taught that Shakespeare's era was a time of change from the Middle Ages to the modern era. People living in a country where they served God and coexisted almost unscientifically with God subsequently transcended God as a result of progress with science and other fields and began possessing a sense of self. Hamlet certainly symbolizes that. I think with Macbeth, Shakespeare described humans who had begun to transcend God, people who are haughty. It is said that "the proud Heike family does not last long (Pride goes before a fall)," but the view of life and death in Macbeth - the sense of the vanity of life - is very much applicable to the Heike sense of the vanity of life, I think.

In Macbeth, people gradually become haughty. Every dream seems to fall apart, however. The autumn leaves symbolize that. Compared to the white of Genji's flag, the Heike's flag is red. The image of the red flags falling at Dannoura is just like autumn leaves being jostled by waves. So initially, there was that poetic sentiment which was described in the work. I believe there are points in common with the classical world.

- The impression I had when I saw this work was that it was very easy to grasp. The number of people who appear on stage is narrowed down, the structure of the story is simplified and the dialogue is also easy-to-understand contemporary language. Were you consciously aiming to make it easy to grasp, or is this the outcome of extracting the essence of Shakespeare's work?

- The impression I had when I saw this work was that it was very easy to grasp. The number of people who appear on stage is narrowed down, the structure of the story is simplified and the dialogue is also easy-to-understand contemporary language. Were you consciously aiming to make it easy to grasp, or is this the outcome of extracting the essence of Shakespeare's work?

Nomura:I always ask Professor Shoichiro Kawai, of the University of Tokyo, to do the translating. What I am aiming for with the translation is to first and foremost have the poem portions made into something that is easy to read in the rhythm of the Japanese language, and to try to use classical Japanese as much as possible. As you would expect, it becomes difficult to read if there is a large number of classical Chinese-type idiomatic phrases. You can understand it when you read it but it is difficult to understand when you hear it, so that area is something I am particular about. Additionally, because the dialogue is garrulous, it is long and you grow tired of it, and since there are various scenes and various characters appear, it is complicated, so I narrow it down to one focus.

As a character, Macduff plays a vengeful role, but my focus is on how much desire Macbeth has when he meets the witches, and how, under some duress, he commits murder and faces ruin.

If we were British, then possibly we would have to perform it as a historical drama, but since we are Japanese I felt it was probably okay not to do it in its entirety. I devoted myself to drawing forth Macbeth's essential qualities more by making a Japanese-style interpretation. A work that formed a precedent for this was Kumonosu-jo (Throne of Blood: a film directed by Akira Kurosawa in which the plot of Shakespeare's Macbeth is transposed to Japan's warring states period), which is an arrangement that has been described as Shakespeare at its best, and one which I think captured the true meaning. However, while obviously we were bound by Shakespeare, we also had to take liberties and present a reason for Japanese people going to the trouble of performing Shakespeare.

We have come to Paris, and now we want to perform in London, the "home ground" of Shakespeare.

[Reference article]

Performing Arts Network Japan

Artist interview: "A glimpse of the 'total theater' that Mansai Nomura envisions as a Kyogen actor alive in the contemporary world." (July 30, 2007).

Mansai Nomura

Kyogen actor Mansai Nomura was born in Tokyo, as the eldest son of Living National Treasure Mansaku Nomura. He was designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Property. He also serves as Artistic Director of Setagaya Public Theatre and Director of Kyogen Gozaru-no-za. In addition to Noh and Kyogen performances at home and abroad, he has also produced and had leading roles in stage performances that utilized Kyogen techniques such as Machigai no Kyogen (The Kyogen of Errors) and Yabu no Naka (In a Grove), as well as Kuninusubito (The Usurper) and Atsushi -- Sangetsuki, Meijin-den (Atsushi Nakajima's The Moon over the Mountain) and other performances that sought to merge classical theater and contemporary drama. His recent key stage performances include Waga tamashii wa kagayaku mizu nari (My Spirit Is the Sparkling Water), Oedipus Rex (directed by Yukio Ninagawa), Hamlet (directed by Jonathan Kent), and Shigosen no matsuri (Requiem on the Great Meridian; directed by Hideo Kanze). He is widely active, having appeared in movies that include Ran (directed by Akira Kurosawa), Onmyoji and Onmyoji 2 (directed by Yojiro Takita), Nobo no Shiro (The Floating Castle; directed by Isshin Inudo and Shinji Higuchi), as well as on NHK's TV show Nihongo de Asobo (Let's Play with Japanese). He has received a large number of awards, including the National Arts Festival New Artist Award from the Japanese Agency of Cultural Affairs, the Art Encouragement Prize for New Artists of the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture and the Kinokuniya Theatre Award.

Keywords

- Theater

- Republic of Korea

- Japan

- United States

- U.K.

- Romania

- Russia

- Noh

- Kyogen

- Setagaya Public Theatre

- William Shakespeare

- Shakespeare

- Macbeth

- Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris

- Scotland

- shite hitori shugi

- Théâtre du Soleil

- The Tale of Genji

- the Tale of Heike

- Akira Kurosawa

- Seoul

- New York

- Sibiu

- Richard III

- Hamlet

- Professor Shoichiro Kawai

- Tokyo University

- Throne of Blood

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…