In the Real World: from A Storehouse of Contemporary Japanese Architecture

Kayoko Ota (Commissioner)

Norihito Nakatani (Director)

Hiroo Yamagata (Executive Advisor)

* Original text in Japanese, translated to English by the Japan Foundation

The opening of the 14th International Architecture Exhibition, part of the Venice Biennale, is finally approaching (June 7 - November 23, 2014). The Japan Foundation has participated in the National Participations section at each Biennale, and is responsible for organizing the exhibition at the Japan pavilion. For the exhibition at the Japan pavilion, a project team led by Commissioner Kayoko Ota has been making preparations steadily for close to one year. The overall theme for all national pavilions in the 2014 International Architecture Exhibition is "Absorbing Modernity: 1914 - 2014." In line with this common thread, the Japan pavilion has taken up the theme "In the Real World," weaving a continuous history of the country's architecture over the past 100 years while placing the focus on the 1970s, and tracing the roots to the underlying strength of Japanese architecture. Prior to the opening of the event, a preview talk entitled "In the Real World--from A Storehouse of Contemporary Japanese Architecture" was held, allowing the public to ask the project team about the details of the exhibition.

The opening of the 14th International Architecture Exhibition, part of the Venice Biennale, is finally approaching (June 7 - November 23, 2014). The Japan Foundation has participated in the National Participations section at each Biennale, and is responsible for organizing the exhibition at the Japan pavilion. For the exhibition at the Japan pavilion, a project team led by Commissioner Kayoko Ota has been making preparations steadily for close to one year. The overall theme for all national pavilions in the 2014 International Architecture Exhibition is "Absorbing Modernity: 1914 - 2014." In line with this common thread, the Japan pavilion has taken up the theme "In the Real World," weaving a continuous history of the country's architecture over the past 100 years while placing the focus on the 1970s, and tracing the roots to the underlying strength of Japanese architecture. Prior to the opening of the event, a preview talk entitled "In the Real World--from A Storehouse of Contemporary Japanese Architecture" was held, allowing the public to ask the project team about the details of the exhibition.

(Excerpt recorded from the preview talk held at the Japan Foundation's JFIC Hall "Sakura" on April 17, 2014)

Building an exhibition that seeks to return to the true essence

Kayoko Ota: First, I would like to talk about the Venice Biennale itself. The first International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale was held in 1980, and the 2014 exhibition marks the 34th year of the event. However, the situation has undergone significant changes since the inaugural event. In recent years, the Biennial Foundation of the Venice Biennale felt a sense of crisis that architecture exhibitions might be moving farther and farther away from the true essence of architecture. Rem Koolhaas, the 2014 Exhibition Director, shared this sense of crisis, and undertook the overall direction for this exhibition with the intention of having the Venice Biennale take the lead in rebuilding architecture exhibitions from the ground up. Hence, this Biennale should be drastically different from the ones before.

Kayoko Ota: First, I would like to talk about the Venice Biennale itself. The first International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale was held in 1980, and the 2014 exhibition marks the 34th year of the event. However, the situation has undergone significant changes since the inaugural event. In recent years, the Biennial Foundation of the Venice Biennale felt a sense of crisis that architecture exhibitions might be moving farther and farther away from the true essence of architecture. Rem Koolhaas, the 2014 Exhibition Director, shared this sense of crisis, and undertook the overall direction for this exhibition with the intention of having the Venice Biennale take the lead in rebuilding architecture exhibitions from the ground up. Hence, this Biennale should be drastically different from the ones before.

The Venice Biennale itself is putting its fullest efforts into being an exhibition produced through fine and detailed research, and which throws out questions to the world based on new practices. While the number of national participations had been 55 in previous years, this has increased to 66 countries this year. These 66 countries will tackle, en masse, the common theme of "Absorbing Modernity: 1914 - 2014." The intentions behind sharing a common topic with all the participating countries are to provide visitors with a global perspective of architecture, and to generate new dialogues and conversations.

The Japan Pavilion is entitled "In the Real World: from A Storehouse of Contemporary Japanese Architecture." It probes and explores the question, "What can happen when architecture truly enters the realm of reality?" Architectural works produced in Japan ever year receive high appraisals from the global community. Why is it able to receive such high ratings? The Japan Pavilion seeks to oresent the answer to this question but in a critical manner.

Considering 100 years of modernization from an economic perspective

Hiroo Yamagata: I would like to give an explanation about the overall view of the exhibition in the Japan Pavilion. The overall theme for the Biennale, that is, to reflect on the past hundred-year history of architecture has been constantly discussed these days. We are witnessing greater uniformity across the globe, and those who are anti-globalization often bring up topics such as "Everyone uses mobile phones" or "Everyone uses computers." In the same way, we wish to bring forth the issue that the same phenomenon is occuring in architecture. Of course, we have achieved advancements in modernization in the past 100 years, and we have moved toward an increasing use of mass production in various aspects of life. However, this is not all there is to this issue. There are differences between cities, such as Tokyo, Hong Kong, and New York. One of our answers, or counter-proposals, is to say that there are various ways of looking at and thinking about a problem. We hope that visitors will be able to take this point of view.

Hiroo Yamagata: I would like to give an explanation about the overall view of the exhibition in the Japan Pavilion. The overall theme for the Biennale, that is, to reflect on the past hundred-year history of architecture has been constantly discussed these days. We are witnessing greater uniformity across the globe, and those who are anti-globalization often bring up topics such as "Everyone uses mobile phones" or "Everyone uses computers." In the same way, we wish to bring forth the issue that the same phenomenon is occuring in architecture. Of course, we have achieved advancements in modernization in the past 100 years, and we have moved toward an increasing use of mass production in various aspects of life. However, this is not all there is to this issue. There are differences between cities, such as Tokyo, Hong Kong, and New York. One of our answers, or counter-proposals, is to say that there are various ways of looking at and thinking about a problem. We hope that visitors will be able to take this point of view.

There are slight differences in the modernization of America, Europe, and Southeast Asia. In economics, we think about these differences through the concept of path dependency. Once a path is made, we can move in various directions by following a unique path. Hence, the paths taken by Japan, Europe, or Asia are all distinct and separate. One of the ideas that we have is that there may be a similar phenomenon in architecture. How is a path determined? It is done by the detailed initial conditions of the land, as well as incidents and coincidences that happen throughout the span of history. For this exhibition, we have decided to focus on the 1970s because various forms of such historical coincidences have happened along the route of similar developmental stages of modernization. There have been many, and varied, attempts to reset or restart the setbacks that we have experienced in modern times, such as the oil shock and pollution problems, as we pondered on how we should think about these problems. We could say that the coincidences that helped to shape the path of modernization later in the future were concentrated in the 1970s. By looking at these events, we believe that we will then be able to visualize the processes of path generation and see the paths that future history will be built upon.

In economics, we often say that events that happen by chance do not occur individually; rather, several such coincidences create a synergy effect. Coincidences are also "manipulated" in order to generate certain synergy effects. These trends were also observed in the case of architecture in the 1970s. One of these was the movement of similar trends in various areas toward different directions. Magazines and other media existed as elements that helped to connect these coincidences. By looking at these, we believe that we will be able to provide a better description of the paths that we have taken in the past 100 years, and the paths that we will be taking going forward.

There is a second issue. While I have talked about modernization and movement toward mass production in the past 100 years, if we were to listen only to what the architects have to say, we may wonder if this truly has a significant relationship with the overall picture of architecture.

Looking at general construction contractors, could we not say that they have built splendid buildings, including structures such as prefab housing and office buildings that are different from creations by master architects? As far as we can tell, it is clear that the two areas are not completely separate. They have had a mutual impact on one another, and created the entire architecture industry through this connection. Even if we were to look at the overall industry, we believe that we can see various coincidences that determined the path of the industry. We wish to highlight this fact to all the visitors by presenting to them the various attempts and efforts made in the 1970s. When visitors look at the exhibits, will they see unique examples, or increasing uniformity across the world through the widespread use of prefabrication, or on the other hand, perhaps something different? It is possible to view the exhibition in various different ways. This is what we wish to present at this exhibition. The Japan Pavilion will put on display the unique perspective that the Japan Pavilion has taken toward these 100 years. Through the Japan Pavilion, we hope to provide to the world some form of recommendation, direction, or suggestion about the future of architecture.

Interpreting 100 years of architecture through the 1970s

Norihito Nakatani: When you enter the storage room in another person's home, I believe you will be curious about the reasons and relationships behind the placement of objects in the storage room. Our aim is to create a storehouse that can arouse that same kind of interest and curiosity. Today, I would like to talk about three points in the work of directing this exhibition.

Norihito Nakatani: When you enter the storage room in another person's home, I believe you will be curious about the reasons and relationships behind the placement of objects in the storage room. Our aim is to create a storehouse that can arouse that same kind of interest and curiosity. Today, I would like to talk about three points in the work of directing this exhibition.

First, I would like to introduce the topic from the perspective of economics. What has Japanese modern architecture produced to date? It is that architecture creates the form of a country, of an economy, or the form that keeps one's position regardless of social contexts. What is of important here is the fact that regardless of changes in the respective proportions of these forms, architecture has been surviving throughout all the eras without disappearing. For example, let us look at the landscape of Asakusa in 1964. Although the number of buildings has certainly increased today, this does not mean that there have been changes to the overall structure. Instead of changing drastically along with the tides of time, I think that it is a city in which the birth of diverse forms that architecture takes in the country, economy, and self-protection is taking place. I believe that the genealogy of buildings generally does not disappear.

Then why did we place our focus on the 1970s? To answer that, we can bring up the opening of the Osaka Expo. Although the values of progress and harmony that have been propounded do not end at the conclusion of the event, it will reach a certain saturation point. Until then, contemporary Japanese architecture had given scant consideration to pollution problems, economic crises, and the oil shock, yet these global issues were happening successively. I am of the view that the individual proposals that were conceived of and implemented amidst the experience of such crises provide an indication for the direction of development of architecture thereafter. I would also like to emphasize that the wonderful thing about Japan's architecture culture is the extremely strong architecture media that has supported such movements.

Next, I would like to introduce the paradigm that shaped the 1970s. I would like everyone to think about the 1970s as one of the lenses that you can use for looking at the past 100 years. The 1970s saw movements that involved observing the city, rebuilding Japan's architecture history, or relooking at Japan through field surveys. The "architecture detective" team led by Terunobu Fujimori, Takeyoshi Hori, and others, were part of this movement. Formalism was also born during this period, almost as if in opposition to the aforementioned movement. This movement involved thinking about reality or reorganizing modern technology by proposing a unique form and further commercializing that idea. This is basically the same as reconstructing modern history. By learning through the vernacular in field surveys, I feel that the problem of how to incorporate subtle forms of settlement and coincidences that had not previously existed in the planning process arises at this point in time.

In the "storehouse" exhibition this year, I drew up diagrams in my proposal as the Director on how to link these various movements. The exhibition team then made use of these diagrams and added their own unique ideas. By sharing these ideas, and over the course of repeated trial and error, we came up with the structure for the exhibition.

Finally, I would like to talk about events related to synergy. During this research process, what I had perceived to be of great importance from the 1970s to the 1980s was the fact that various people were connected to one another in various ways, and through various movements and actions, produced some form of result. In relation to this, I would like to talk a little about the commercial housing study group led by Toyo Ito. The commercial housing study group, the house in Honcho, Nakano known as White U, the Silver Hut, and the Sendai Mediatheque are amongst Ito's works that became transitional points in his career history. Within the research circles, the activities was not noticable much and was carried out pretty quietly by the comercial housing study group. However, the study group has left notes and records, saying about building houses of a new type of product, rather than residences to be the works of an architect, or conventional residences built for commercial purposes. Furthermore, the study group carries out analyses for overcoming the hurdles of consumer society, as described by Ito himself. And these efforts probably led to the idea of Silver Hut, I think. White U has made the transformation from originally being a piece of work with formalism elements, to being an extremely flat residence for commercial ones. I think that such developments are very important. In short, it is significant how creators arm themselves with the power to relativize themselves and their own work.

There are various threads behind this. For example, there is a "direct dealing" format that Osamu Ishiyama came up with, which involves having architects deal directly with other architects for materials and parts. Ito had used this method on his previous House in Kasama. In other words, we are seeing a development that seems to be a reversal of the movement propounded by Ito so far.

If we were to trace the flow for Ishiyama even further, we would find an even earlier movement. By building a house through the application of a modern technique that he had learned from an engineer named Kenji Kawai, which involves closed conduits for sewage uses, he explored how to apply modern techniques for general use. We can now draw up a schematic diagram with the direct dealing format coming before the commercial housing study group.

Who had brought active architecture movements to the 1970s? What were those movements, and in what form were they brought onto the scene? Based on this, we hope to reconsider one of the starting points for Japan over the last 100 years. We would like the visitors to explore architecture and history, editors and architecture, and various three-dimensional flows, in the same way that they would explore a storehouse.

The crossroads of Japanese Architecture that is referred to as the world's greatest of its kind

Ota: Placing the focus on the 1970s may appear to be simply holding an exhibition about architecture in the 1970s. However, that is not the case with us. The 1970s is an important era because of the major economic setbacks that the country experienced at the time. The Expo contributed to inflation, and the architecture industry was concentrated on general construction contractor work, resulting in a shortage of jobs for the young. In 1973, the oil shock hit, and there were no jobs at all. What did these people (young architects of the time) do during such times? They took extreme measures. They went onto the streets and observed the flow of the world, or like Ishiyama, entered the markets and industries, and searched for something they could do as architects. Not only the architects, but also historians and other people also left out of typical career positions and wandered around the streets of Japan with their own foot to uncover the history of contemporary Japanese architecture that has not been written into official historical records. Even if there were others like them, there is something truly incredible about why this movement had emerged in the 1970s. However, I think that we can say that this movement was backed by the economic setbacks experienced by Japan, and that it was a situation that had occurred in Japan that had crossed over one of the peaks along the road of modernization to meet the next challenge. Nakatani-san has described the trial and error process that Toyo Ito had gone through, which was unknown to many people. In fact, Ito had not been the only one who had to face such struggles; rather, it was a common experience for everyone.

Japanese architecture is touted to be of the highest levels in the world. I do not think that is an exaggeration. Why does Japan have such strength in the field of architecture? No one can provide the answer to that question. In this exhibition, we will explore these roots and provide hypotheses that we are confident about. This is what we found by probing into the events that happened in Japan as a typical or unique example of modernization in the world. In the 1970s, Japan had the drive to shape the power of architecture that was highly appraised around the world. We would like to disseminate these ideas. Hence, architecture that is highly appraised in Japan is now emerging, while the architecture that had originally existed before the 1970s, and of course Japanese architecture from the Kamakura to the Edo eras, will continue to exist. What did Japanese architects do at the dawn of modernity and civilization? While it is not typical to do so, we wish to show a 100-year process through this form.

Members of the Japan Pavilion (from left: Kayoko Ota, Tomomi Ishiyama, Hiroo Yamagata, Norihito Nakatani, Keigo Kobayashi, Jin Motohashi, Takeshi Yamagishi)

(Editor: Ayako Tomokawa / Photography for the preview talk: Kenichi Aikawa)

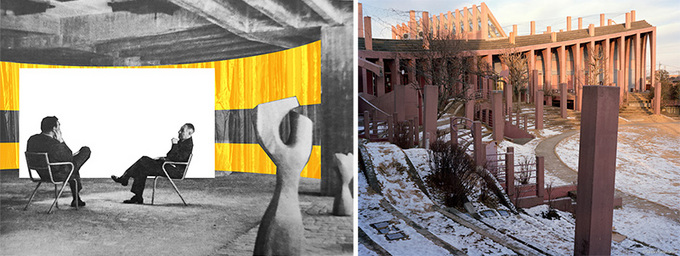

Japan Pavilion Installation Image © Keigo KOBAYASHI

(Left) Japan Pavilion Installation Image (Piloti) © Keigo KOBAYASHI, (right) Shinshukan / Atelier Zo © Takeshi YAMAGISHI

(Left) Private House / Jiro Murofushi © Takeshi YAMAGISHI, (right) Private House / Hiroshi Hara © Takeshi YAMAGISHI

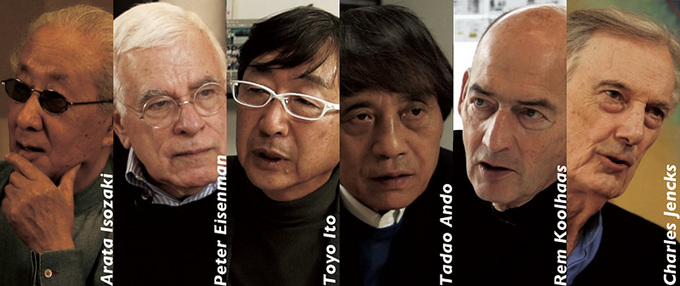

Film for the Japan Pavilion 2014 directed by Tomomi Ishiyama © Tomomi ISHIYAMA

A documentary film that will be screened at this exhibition. The film features architects and architectural historians who have left their mark on history, and tell the truth about events as well as the unique characteristics of contemporary architecture in Japan, from a global perspective.

Kayoko Ota

Exhibition Organizer / Editor

For 10 years until 2012, Ota worked on exhibition planning and book editing at AMO, a think-tank arm of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). She served as co-curator for the AMO exhibition "Cronocaos" (2010) and "The Gulf" (2006) at the International Architecture Exhibition in the Venice Biennale, and as curator for Prada's "Waist Down" from 2005 to 2009, the OMA-AMO retrospective exhibition "Content" in 2003 and 2004, and the Hong Kong and Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture in 2009. Among the books she has edited are Project Japan: Metabolism Talks... (Taschen 2011; Heibonsha, 2012), Post-Occupancy (Editoriale Domus 2005), and Waist Down (DAP 2005). In 2004, she was named deputy editor at DOMUS. Until 1993, she served as joint director of the Workshop for Architecture and Urbanism and joint editor of the magazine Telescope.

Norihito Nakatani

Professor, Department of Architecture, Waseda University

Nakatani is an architectural historian noted for a variety of unique activities. These include studying the writings of early-modern-era carpentry, and the continuity of land characteristics and their influence on the present day (theory of pre-existing characteristics); overseeing a project to document change by revisiting the houses that the Japanese "modernologist" Kon Wajiro visited in the early 20th century; and more recently, researching villages that have existed for a thousand years. He has also established Acetate, an editing/publishing organization devoted to putting out books by rare and ubiquitous people. His own books include Revisiting Kon Wajiro's "Japanese Houses" (as part of the Rekiseikai group, Heibonsha, 2012), Severalness+: The Cycle of Things and Human Beings (Kajima Shuppankai, 2011), and The Study of Classical Literature, the Meiji Period, and Architects (Ikki Shuppan, 1993). In 2013, Nakatani received the Kon Wajiro Award by the Japan Society of Lifology and the Writer's Award by the Architectural Institute of Japan.

Hiroo Yamagata

Translator/critic

After studying at the Department of Engineering at the University of Tokyo, MIT (Cambridge, Mass.), and receiving a master's degree from the both, Yamagata joined a major the Nomura Research Institute. While conducting surveys for foreign aid projects related to infrastructure and urban development, he is also active as a translator and critic, dealing with a wide range of issues including free software, contemporary literature, economic theory, environmental problems, and architecture/urbanism. Among his books are Declaration for New Traditionalism (Shobunsha/Kawade Bunko), Linux Japanese Environment (O'Reilly Japan), and Just a Book on William Burroughs (Omura Shoten). He has also published many translations of foreign books including Jane Jacobs' The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Kajima Shuppankai), and Paul Krugman's The Age of Diminished Expectations (Chikuma Bunko).

Keywords

- Architecture

- Film

- Economics/Industry

- History

- International Exhibition

- Japan

- Italy

- Kayoko Ota

- Norihito Nakatani

- Hiroo Yamagata

- Venice Biennale

- Rem Koolhaas

- Tokyo

- Hong Kong

- New York

- Asakusa

- Osaka Expo

- Terunobu Fujimori

- Takeyoshi Hori

- architecture movements

- Toyo Ito

- commercial housing study group

- White U

- Silver Hut

- Sendai Mediatheque

- Tomomi Ishiyama

- Kenji Kawai

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…