Sugimoto Bunraku: A New Tradition of Puppet Theater Breathes Japanese Soul into Lifeless Wooden Puppets

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Contemporary artist

The 2012 premier performance of "Sugimoto Bunraku Sonezaki Shinju: The Love Suicides at Sonezaki" at Kanagawa Arts Theatre has no doubt gained quite a number of people being intrigued by the depth and the intricacy of Ningyo Joruri Bunraku for the first time. This theatrical work was later refined with new features such as a video installation by contemporary artist Tabaimo, and toured Madrid, Rome, and Paris in 2013. How was the world of Bunraku--a separate art form from the other two types of traditional Japanese theater, Noh and Kabuki--received by the European audiences who were less familiar with traditional Japanese culture and the distinct view of life and death reflected in the narrative?

--There was a comment from the audience in the post-performance survey that said, "The harmonious collaboration of the puppets, the shamisen players and tayu (the chanters) redefined the concept of theater."

SUGIMOTO: There are puppet theaters everywhere around the world, but most are primarily for children. Japanese Bunraku, on the other hand, is for adults and it surprised the Europeans with the high level of theatrical sophistication as well as the quality of the artistry of the puppets and other stage presentations.

--What were the reactions of some of the discerning cultural figures with whom you are friends, such as artist Sophie Calle and actress Isabelle Huppert?

SUGIMOTO: Isabelle usually stays straight-faced and rarely shows her true feelings, but she told me our show made her cry. You are just looking at the man who made Isabelle Huppert, of all people, cry! Sophie was reportedly out partying all night the night before to celebrate her birthday, but still made it to the show. She is also a tough critic, but I'm pleased to say she gave our show a thumbs-up.

--What stood out the most to you of all the reviews and critiques you received from the overseas media?

SUGIMOTO: The French newspaper Le Monde gave us the biggest coverage; we made the front-page headline the morning following our premier performance in France. No one imagined Sugimoto Bunraku would trample politics, the economy and other news stories to grab the front-page headline. I was told for Le Monde this was a rarity that happens just once or twice a year.

--The Le Monde headline read "Sugimoto breathed souls into the lifeless wooden puppets."

SUGIMOTO: The puppets are nothing but inanimate, wooden figures. They look alive on stage not because they are well made, but because humans have a soul--the capacity to project their own feelings onto something and be affected enough to shed tears. One article remarked that our show provided an opportunity to ponder about the human soul. Ningyo Joruri is an enigmatic form of theater in that way--it has that elusive and complex quality.

--Would you say that the language and cultural barrier helped, rather than hindered, your work being accepted as a comprehensive art form in a straightforward way?

SUGIMOTO: Bunraku has regularly toured Europe and has already enjoyed a good reputation there. Sugimoto Bunraku, however, takes a vastly different approach to staging compared to the conventional versions. Some people especially appreciated our contemporary interpretation.

--During the press conference before the performance, one of the puppeteers notably commented that Mr. Sugimoto's adaptations made everything very challenging. He complained about the pitch-dark stage, the fact that he had to remain hooded throughout the performance, the fast pace that barely allowed him to breathe, and so on and so forth....

SUGIMOTO: Sugimoto Bunraku was launched with the fundamental goal to reproduce the world of "Sonezaki Shinju" in the exact same way it was presented in the early 18th century Edo period. Back then, lights were not needed because a show usually took place during the day, before sunset. Evening performances had to be given with candle lights. I had the show performed in darkness. It didn't exactly mean to represent the world of Junichiro Tanizaki's essay titled In Praise of Shadows, but we tried to faithfully recreate the atmosphere of the Edo period. Thus, the stage simply had to be dark.

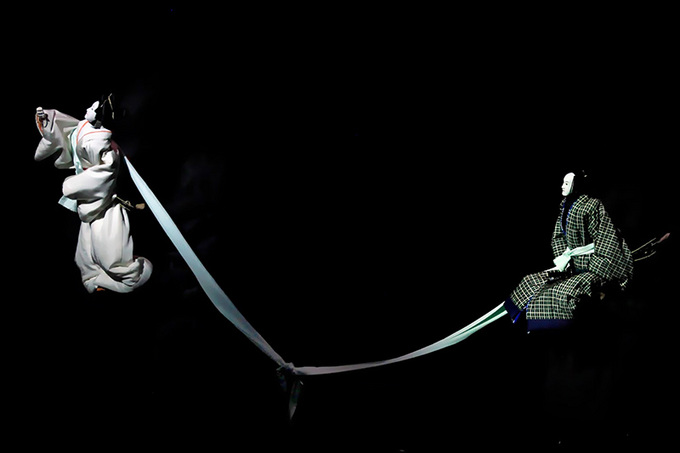

And in that darkness, the audience sees the silhouettes of a team of black-clad puppeteers, which, in a way, look like a scene from a ballet. I asked the cast to be well aware of their movements to be seen as dance. I wanted not only the puppets but the puppeteers to move gracefully on stage, as if they were a corps de ballet.

--That is a rather bold recreation or arrangement of a traditional form of theater. The stage set-up was also novel: In Bunraku the puppets only move sideways but in the Sugimoto version there are vertical as well as horizontal movements that give depth to the space. Then there is the innovative use of lighting and the animation.

SUGIMOTO: The butterfly video we used during the premier performance was something I got online. The artist Tabaimo approached me after the show and gave a negative feedback on that video, so I asked if she would be interested in creating a piece for us and she agreed. Tabaimo put so much effort into her work. That initial video lasted a mere 15 seconds but the new one was much longer, running through most of the "Kannon Meguri" scene. If you look closely, you'll find various hidden argots in it. It is a beautiful piece of work.

--The "Kannon Meguri" overture in the original script has long been omitted in other conventional productions. Tell us how you came to revive the scene in yours.

SUGIMOTO: After about two decades of successful productions since its 1703 premier, all "Sonezaki Shinju" performances were banned in Japan for sparking a rash of copycat suicides. Not a single performance was given for the next 200 years. When it was finally revived in 1955, the overture scene was cut because the play would take no less than four hours if enacted in its entirety at the slower pace of the old days. Thankfully though, the authentic gidayu (the narrator) script remained intact.

While Sugimoto Bunraku places an immense importance on a faithful reproduction of the original script, we didn't want to bore the audience with an extremely long play. So I suggested some lines be delivered at tongue-twisting speed, like in rap music. I also had the play open with a piece of music, which had not been heard of in Bunraku before. I asked the composer to write something reminiscent of a guitar solo by Jimi Hendrix, and had it played in the dark on a futozao (thick-stringed) shamisen.

--Is the "Kannon Meguri" scene important in understanding the story?

SUGIMOTO: I reinstated the scene because it provides a crucial context for the play. In the current version that omits this part and goes straight to the scene at the shrine, it is not at all clear what motivates the two lovers to take their lives. While The Love Suicides at Sonezaki is a love story, its central underlying theme is a deep Buddhist faith, manifested in the unwavering longing to have one's spirit guided to Amida Buddha's Pure Land.

A preamble to what follows later, the overture scene finds the heroine, Ohatsu, making a pilgrimage to a Kannon temple. The act calls attention to the fact that she was a devoted believer in Kannon (Buddhist deity of mercy). Doomed to live apart in this life, she and her lover Tokubei come to believe that if they kill themselves for true love then Kannon will reunite them in the afterlife. You wouldn't understand this if you miss the deleted bit in the original script.

--A double suicide is a strange concept even for modern-day Japanese people. It must have been quite a challenge for the European audience to appreciate the sentiment behind the narrative.

SUGIMOTO: The three cities we toured are all Christian societies. Catholicism views suicide as a mortal sin. Their belief is that human life is a temporary gift from God and to destroy it is a great sin no matter what the reason.

The Love Suicides at Sonezaki is often compared to Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, but their death is not a double suicide. They take their lives out of sorrow that really resulted from a misunderstanding. The logic that the Kannon faith contributed to the decision of Ohatsu and Tokubei to kill themselves may not easily be understood in a Catholic society. Still, the audience was deeply moved by the scene where the couple's journey ended in their deaths, with some people left in tears. There must be something in the narrative that transcends faiths.

--Although they agree to commit a double suicide, Ohatsu and Tokubei aren't exactly on the same page, are they?

SUGIMOTO: No, they aren't, and this rendering of the characters is unique to Sugimoto Bunraku. The woman is fully devoted to her faith and takes the lead in orchestrating their suicide, guiding along her hesitant partner. The script describes a scene where Ohatsu communicates silently with Tokubei, who is hidden under the verandah of the Tenmanya teahouse, by stretching out her bare foot to caress him. With just her foot, she makes sure he is really willing to die with her. Clearly, women called the shots even in those days in the Edo period. Poor Tokubei had no choice: cheated out of money and disowned by his master, he had no future. Ohatsu's situation, on the other hand, was not so dire that she had to end her life. Nevertheless, she invites him to commit suicide and head for the Pure Land with her, and then they do together.

When it was first performed in the Edo period, "Sonezaki Shinju" became so popular that it is said to have set off a spate of copycat suicides. The ruling government took a number of prevention steps, of which the most effective proved to be a ban on funeral services for suicide couples. The message was, "With no funeral and no grave you can't reach the Pure Land, so you better think again."

--Tell us about the different strategies you used in each city to help the audience better understand the narrative and its nuances.

SUGIMOTO: In Spain, before the opening of the play we gave an introductory talk that would resonate with the audience. In Rome, the audience was initially given earphones to listen to the simultaneous interpretation, but the sound leaking from the earphones disturbed both the performers and the audience. So in the second half we told the audience the device was out of order and carried on with the show without the subtitles or the earphones. In Paris, we offered supertitles displaying short, snappy translations in old-style French. This worked the best, I think.

--Are there plans for Sugimoto Bunraku to make more overseas tours in future?

SUGIMOTO: Our next overseas performance is already quietly in the works. It's going to be another one of Chikamatsu Monzaemon's sewamono (a domestic play). I have worked in various fields of art, including photography and architecture. What differentiates performing arts from these fields is its momentary and transitory nature and personally I like to see a work evolve, from one performance to another. Theater is an art form that plays an important role in understanding the human soul. It is crucial in analyzing the mentality of the ancient peoples, and I have no doubt theater will continue to be a core part of my career.

Premier performance in Madrid, September 27, 2013

Performance in Rome, October 4, 2013

Performance in Paris, October 10, 2013

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Born in Tokyo in 1948. After graduating from Saint Paul's University, he moved to the United States in 1970 and started his career with photography in New York in 1974. Sugimoto has received international reputation as a photographic artist through his solid technique and clear concept seen in the series such as Seascapes and Theaters, and his works are collected by major art museums throughout the world. In 2008, Sugimoto held a solo exhibition at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, entitled "History of History", which consisted of both his own works and works from his collection of antiquities. In recent years he has been expanding his field of activity to literary and architectural work, and in 2008 he published his second title of essays, Utsutsu-na-zo (Shinchosha). The same year, he founded New Material Research Laboratory, and he was involved in the interior design and landscaping of the Izu Photo Museum, which opened in 2009. He also designed the entrance space of oak omotesando in Tokyo, which opened on April 4, 2013. An appreciator of traditional arts, Sugimoto has also led the direction of the sanbaso production "Kami hisomi iki" in 2011, was presented at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in March 2013 and once again in Tokyo in April 2013.

His works have won many awards, including the Mainichi Art Prize in 1988, the Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography in 2001, and the 21st Praemium Imperiale in 2009.

Keywords

- Traditional Arts

- Theater

- Music

- Philosophy/Religion

- Japan

- Italy

- Spain

- France

- Sugimoto Bunraku Sonezaki Shinju: The Love Suicides at Sonezaki

- Bunraku

- Kanagawa Arts Theatre

- Ningyo Joruri Bunraku

- Tabaimo

- Madrid

- Rome

- Paris

- Noh

- Kabuki

- Shamisen

- Puppet theater

- Sophie Calle

- Isabelle Huppert

- Le Monde

- Edo period

- Sonezaki Shinju

- Junichiro Tanizaki

- Jimi Hendrix

- Christianity

- Romeo and Juliet

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…