The Power of Graffiti: An Interview with Titi Freak on the Recovery Project in Ishinomaki

Titi Freak, Graffiti Artist

Enrico Isamu Oyama, Artist

Internationally acclaimed Brazilian graffiti artist Titi Freak launched a project together with local groups in Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, an area devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake. The artist traveled from Brazil for the project, during which he worked together with residents of temporary housing to create wall murals. With his strong personal ties to Japan, what did he see and feel in the Tohoku region? The interview was conducted by up-and-coming artist Enrico Isamu Oyama.

What can an artist do?

OYAMA: Hello, I'm Enrico Isamu Oyama.

To start off, I'd like to tell you a little bit about myself, because I think there's a reason I was chosen to do this particular interview.

I was born and bred in Japan, but my father is Italian and my mother Japanese. So I may be exaggerating things but I already feel an affinity to you since you are a Brazilian of Japanese descent.

Of course, that's not the only thing. I am usually engaged in artistic activities, especially creating works from a perspective that take in both graffiti or street art and contemporary art. I also do a bit of writing as well.

I'm sure you share my feeling that in these past decades graffiti or street art has established itself as a cultural phenomenon all over the world, and that it's a very exciting genre where each day someone somewhere in the world is experimenting with a new form of expression. I believe another wonderful aspect of this genre is that artists can have exchanges and collaborate with each other on an independent level through their own networks, transcending national borders and regions.

With this global trend of graffiti or street art in mind, I believe it's very meaningful that you have been invited by the Japan Foundation for this project, and that you have committed your efforts as a graffiti artist towards the recovery from the 3.11 earthquake, a catastrophe of historic proportions for Japan. (*)

In this interview, I hope I'll be able to ask you some things from my perspective as an artist, as someone also involved in graffiti or street art, and as someone who is half Japanese and half not.

To start, let me ask your first thoughts when you saw the news of the earthquake in Japan, and how you felt after actually visiting the devastated sites and during the graffiti art project, communicating with the people in the afflicted areas through your art. If possible, we'd appreciate if you could also tell us how the project came to life and talk about the process of making it happen.

* [Editorial note] Titi Freak produced graffiti art and offered workshops in Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, in December 2011 as a project by the Japan Foundation.

"Community x Graffiti @ Temporary Dwelling (Tomorrow Business Town) in Ishinomaki" Ishinomaki City Tomorrow Business Town, December 3 to 11, 2011

http://www.jpf.go.jp/e/intel/new/1112/12-03.html

People watching Titi Freak work

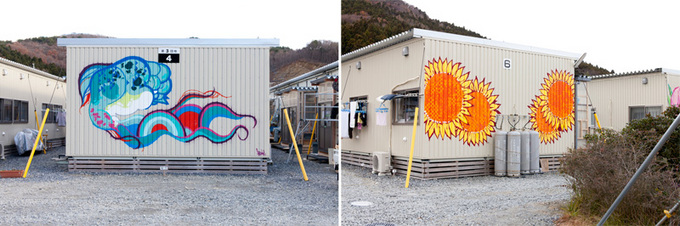

Murals decorate the sides of temporary housing

Shocking scenes, remarkable people

TITI: Hello, Oyama-san, it's a pleasure to meet you.

I was actually in Brazil when the earthquake and tsunami hit the Tohoku region. I was watching NHK cable television with my family, and we looked on in horror and disbelief. It took a while to really take in what was happening.

Then, the news was on Brazilian television and it was like a scene from the movies. What I felt was a mixture of pain, anger, sadness, and a feeling of sheer helplessness, unable to do anything in the unfolding disaster.

My wife is Japanese and I am a third-generation Japanese-Brazilian. (My grandparents arrived in Brazil on the Kasatomaru as part of the first group of immigrants from Japan.) So, I really felt I had to do something to help those people.

At the end of March 2011, my wife and I produced two block prints with the help of a gallery in Sao Paulo, and decided to donate the sales to support the recovery of the Tohoku region. We soon found buyers for both and donated the money to the Japanese Red Cross Society in September.

Shortly before the March earthquake, my wife and I had just decided to go and live in Japan for a while. It had been something we'd been thinking about for some time. My wife's family is in Osaka and our son is still very young, so we thought that living in Japan would be a good experience for him. I also thought it could be important for my work.

As such, I wanted to go to Japan after the earthquake and make myself useful in the Tohoku region, but I also knew very well that things might not be that easy in Japan, especially since my art was graffiti.

It was then that I received an email from the Embassy of Brazil in Japan and the Japan Foundation about the graffiti art project in Ishinomaki. I can only say it was incredible timing, and it solidified my resolve to go to Japan.

Then, we spent about two months preparing the Ishinomaki project to produce graffiti art and offer workshops for the people in temporary housing. Soon, the residents approved the project, and by November 2011, immediately after getting their approval, I was already meeting the people involved in Japan and getting ready so the project could begin in December before it started snowing in the afflicted areas.

I produced 15 paintings in the 10 days I spent with the residents in Ishinomaki, and it was an invaluable and unforgettable experience. Actually being there where the tragedy had occurred and walking through the places ravaged by the tsunami was absolutely devastating. Nothing has ever shocked me more, and it made me reflect on the meaning of life.

What was also remarkable was that though it had been such a horrific, heartbreaking experience, everyone was working hard to try and restore their towns and lives, and not one of the survivors showed any sign of giving up. I met a man who had lost his house, his friends, his family, and everything in the tsunami, and though he had such grief in his heart, he said he couldn't just curl up and cry, and that because he had survived the tsunami he had to look ahead and keep on going. The people there weren't angry even though they had gone through so much. That left a deep impression on me.

Hesitation, dilemma, and degrees of impact

OYAMA: Like you, many artists in Japan also launched various initiatives after the earthquake. The most common of these were charity events, where the proceeds were donated to the afflicted areas. Others involved producing art works or conducting projects on the theme of the earthquake or nuclear plant disaster.

On the other hand, some artists were very hesitant to take action after the disaster. Or, even among those who did take action, many decided to do so only after some hesitation.

I'm sure they each had their own reasons to hesitate, but I think that to some degree they all must have found themselves in a dilemma, wondering whether art could really help in a catastrophe like the Great East Japan Earthquake, or it would simply be self-indulgence on the part of the artist. To put it another way, the Great East Japan Earthquake had been such a profound shock for the Japanese that it made people feel this way.

Again, I think how people saw the disaster also varied greatly depending on how strongly they were affected by it. For example, the people in Tokyo of course were not hit by the tsunami, but they did feel the potential threat of the nuclear plant problem. So I think there was some confusion among people as to the extent of the impact they had received--if they were victims or not and of what--and about how they should direct their recovery efforts.

In this context, I think what you did was really significant, that you visited the devastated areas as a Japanese-Brazilian with a unique perspective, and that you succeeded in connecting with the local people through art, bringing a positive atmosphere to the area.

At the same time, with the above dilemma in mind, I am interested in what you think about the potential of art to contribute in a historical catastrophe like this earthquake. Could you talk a bit about that?

Testing the power of graffiti

TITI: I believe that art can somehow change people. Since graffiti in particular is a street art and one of the forms of expression in which the artist has the most contact with people, I knew it could provide opportunities for communication. The project members including myself also believed that this project could help boost people's pride. That is because I felt that the colors in my work and the actual act of drawing can appeal to people's sensitivity.

Ishinomaki does not have a graffiti scene like Sao Paulo or New York or other major cities, and I know how closed Japanese communities can be towards certain things. So, just as you mentioned "hesitation," I did feel a little worried that the local people might not like my work, or might not welcome a Brazilian artist coming along with a can of spray paint in hand and drawing on the walls of their homes.

In fact, I did feel that people were eyeing me suspiciously for the first couple of days. But as the days went by and my work started to take shape, it was clear that the residents were starting to behave differently towards us. They would come up and talk to me, or they would talk about my work with each other, and the children wanted to play near my graffiti. I felt they enjoyed watching me draw and being there with me. During the 10 days of work, I spent my off hours with the people as well, and this allowed me to get closer to them.

By the time the project was coming to an end, you could see people smiling, and it was clear that they were truly happy with my work. In Japan, "art" usually refers to paintings and sculptures, so it was very interesting and moving to watch people gradually come to understand my style of art.

In the end, my graffiti managed to touch the hearts of the people in the region. They came out of their houses more often and started talking to each other more. I think that it may even have helped them grow fond of the place. To be honest, I didn't think it would have such a strong impact.

I made many friends in Ishinomaki. Everyone was warm and friendly and I will never forget them. I hope to visit again before the end of this year to see them all and to continue the project by drawing more graffiti in other parts of the city such as the stores and restaurants that are being rebuilt.

Disaster and art in a historical context

OYAMA: I think you're quite right that graffiti allows you to really connect with people's daily lives because it is street art.

Certainly, I don't think Ishinomaki had its own graffiti scene. On the other hand, I'm reminded of the movement by the Barrack Soshokusha established by Wajiro Kon just after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 in Japan--a historical precedent of trying through art to add color to a place that is suffering some sort of adversity. I feel that your Ishinomaki graffiti project is a contemporary version of this initiative.

It's a shame we've run out of time, but if we get the chance in future, I'd like to hear your views on that, too.

Thank you very much for this interview. I'll have to end my questions for today. I look forward to seeing what you do in the future and hope you will continue with the Ishinomaki project.

A continuing relationship

TITI: Thank you. It was a pleasure talking to you.

I'm also very glad I could be of help to other people through my art. In April, I hope to return to Japan and meet the people of Ishinomaki again and do some paintings in other places.

Some day, we might have the opportunity to work on an art project together. I hope to see you again then.

In front of a piece with the local residents

Ishinomaki Temporary House Graffiti Art Project Report

Titi Freak will talk about his activities in Ishinomaki at his lectures "What can art do for recovery?" in Brazil.

The lectures will be held at the University of Sao Paulo on March 20, Sao Paulo Museum of Art on March 21, and Paranaense Museum in Curitiba on March 23. There will also be screenings of images from the Great East Japan Earthquake with the lectures.

Titi Freak

Titi Freak

Born 1974 in Sao Paulo, Brazil. An internationally renowned Japanese-Brazilian artist, leading the graffiti art scene in Brazil. Produces graffiti art officially with permission from or at the request of municipalities or owners of buildings at various venues. Works with many leading companies including NIKE, adidas, and CONVERSE. Also produces graffiti art at the invitation of numerous organizations around the world, and holds frequent exhibitions at galleries worldwide. Fusing eastern and western cultures and expressing the themes of racial discrimination and poverty, his work has received high artistic acclaim.

http://titifreak.blogspot.com/

Enrico Isamu Oyama

Enrico Isamu Oyama

Artist born 1983 in Tokyo to an Italian father and a Japanese mother. Produces paintings, installations, and murals based on his recurrent motif of Quick Turn Structure. Has been expanding his scope of activities, such as providing art work for COMME des GARCONS' 2011 fall Paris Collection. Installations include "Aichi Triennale 2010" in Nagoya City (2010) and "Padiglione Italia nel mondo: Biennale di Venezia 2011" at the Italian Institute of Culture in Tokyo (2011). Co-author of Architecture and Cloud: Joho ni yoru kukan no henyo (spatial transformation via information) (Millegraph, 2010), and author of the thesis "Banksy's Literacy--From Surveillance Gaze toward Transparent Sight" (EUREKA, August 2011 Issue, Seido-sha). Asian Cultural Council 2011 Fellowship. Currently resides in New York.

http://enricoletter.net/

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…