Evolving Cosplay, Manga, and Anime Sweeping the World

Roland Kelts

Thomas Sirdey

Marc Perez

Toshihiro Fukuoka

These days, masses of people are flocking to anime conventions around the world. It seems to be a craze suddenly spreading like wildfire.

The United States alone hosts more than 200 such events each year, while conventions have also been sprouting up all over Europe, ever since the first 2000 Japan Expo in Paris. To give an idea of how fast it has picked up steam, the number of Japan Expo visitors has shot up from 3,200 in 2000 to 192,000 in 2011. The phenomenon is not limited to the United States and Europe. Brazil has its biannual Anime Friends and India launched the India Anime Convention in 2011, attracting 20,000 visitors. China had the Japan Anime Festival in November 2011, which was jointly hosted by the Japanese and Chinese governments, and this should become even more exciting in 2012 when people will be celebrating The 40th anniversary of the normalization of Japan-China diplomatic relations. Southeast Asia is also seeing a gradual increase of events, cosplay conventions in particular, as with Vietnam's ACCtive Expo, which started in 2007.

ACCtive Expo in Hanoi, Vietnam

ACCtive Expo in Hanoi, Vietnam

Roland Kelts, Japanese pop culture expert and author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the US, explains how the trend has developed. "It began with the French and the Americans followed. Since then it seems to have spread to South America, Spain, and the UK."

In the '90s, anime fans overseas usually conformed to a certain type. American anime fans used to be mainly Asian Americans or young white men, those that are often described as geeks or otaku as they are called in Japan. But this is no longer true--the audience has diversified significantly since the mid-2000s. Kelts says, "At the New York Anime Festival now, you'll see more African Americans, Hispanics and Europeans, rather than white guys, who are now more of a minority."

New York Anime Festival in New York, United States

New York Anime Festival in New York, United States

The Anime Expo in Los Angeles is the largest convention in the United States. Marc Perez, CEO of Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation (SPJA) which organizes the event, says that the dominant percentage of men at conventions on the West Coast in 2000 has decreased gradually against the overall increase in visitors, and that women now account for more than half. In 2011, the Anime Expo marked the highest-ever number of visitors at 120,000. Perez says, "There are more white, Hispanic, and Native Americans now, pushing down the percentage of Asian Americans."

Anime Expo in Los Angeles, United States

Anime Expo in Los Angeles, United States

Thomas Sirdey, one of the Japan Expo founders, says the Japan Expo in Paris is also seeing more women. "When it first started, practically all of the visitors were men. But beginning in 2006, more women have discovered Japanese culture through music and fashion, and mangas for girls are becoming the current 'thing'."

Why the sudden spread of anime conventions overseas? The main reasons are that young people have enthusiastically embraced cosplay (dressing up as anime characters; literally from the English words "costume" and "play"), and the conventions serve as places where cosplay fans can meet or congregate as a community. Kelts says, "In rural areas of the United States, young people who have become anime fans through the internet find others in their local area and rent a car together to drive to anime conventions. What they're looking for is a means of escape from everyday life. Dressing up as anime characters during the convention period enables them to express themselves. The events provide settings for a community formed by people who share the same interests and understand each other."

Toshihiro Fukuoka, Chief Editor of Weekly ASCII and Tokyo Kawaii Magazine, has traveled to various conventions including those in Barcelona, Marseille, New York, Baltimore, and Los Angeles since 2009, when he first visited the Japan Expo in Paris. He says, "You see people in costumes on the trains heading for the conventions and photographers at the venue taking pictures everywhere. It was surprising to see Japanese anime culture being so eagerly embraced overseas and how people were enjoying themselves, each in their own way."

One of the biggest events in Japan is the Comic Market (Comiket) , which attracts a total of 600,000 visitors during its three-day spree. But the major difference from other conventions overseas is that the Comiket is mainly about selling self-published magazines and does not focus on cosplay. Abroad, the cosplay culture is so widespread now that, for example, in Anime Expo, 75% of the visitors spent at least a day as cosplayers. As if in response to this cosplay boom overseas, Japan has also established an event specifically designed for cosplay--the World Cosplay Summit held in Nagoya since 2003. Brazil has qualifying rounds for the World Cosplay Summit, and similar preliminary contests may also be held at other conventions in various locations. In 2010, the winner of the World Cosplay Summit visited Vietnam, demonstrating how cosplay activities are also gaining force in international exchange.

World Cosplay Summit in Nagoya, Japan

World Cosplay Summit in Nagoya, Japan

While cosplay is becoming something of a boom overseas, Fukuoka points out that the way in which countries and regions have added their own spin to the approach is also interesting.

"When I went to the Otakon, hosted by the city of Baltimore, Maryland, I watched a delighted crowd applaud a cosplayer act out a scene from Fullmetal Alchemist in which Lieutenant Colonel Roy Mustang dies, complete with telephone box. While American fans are into performances, the Paris fans place more importance on loyal representations of the characters, respecting the original work. There also seems to be a kind of rivalry between Paris and the States."

Otakon in Baltimore, United States

Otakon in Baltimore, United States

Fukuoka adds that the country twist does not only manifest itself in cosplay. "In Spain, there's a current boom for Japanese culture, so much so that Haruki Murakami became the number one best-selling author in 2010, and the anime, Crayon Shinchan is already well-known to young and old alike. Meanwhile, in Marseille, karaoke is the main attraction at their event. I saw lots of people singing the Pokémon theme song together in Japanese. Then again, the first to discover Hatsune Miku outside of Japan was the Kawaii Kon in Hawaii."

MIKUNOPOLIS in LOS ANGELES in Los Angeles, United States

MIKUNOPOLIS in LOS ANGELES in Los Angeles, United States

©Weekly ASCII Magazine

While the New York Anime Festival is an event that people can visit casually as a part of their daily urban life, the Los Angeles Anime Expo is a huge festival where hardcore cosplayers come from all over the United States and Canada to meet once a year. In Seattle, fans of various ages, from young to middle-aged, come to enjoy cosplay. The favorites also slightly vary from venue to venue: Naruto and One Piece is popular in Paris, and Bleach and Hetalia: Axis Powers in Los Angeles. As Fukuoka suggested, if you go to the Salón del Manga in Spain, you can encounter Spanish fans donned in costumes of older anime characters such as Crayon Shinchan or Urusei Yatsura.

Salón del Manga in Barcelona, Spain

Salón del Manga in Barcelona, Spain

So how do the fans overseas get hold of information on Japanese manga and anime? According to Japan Expo's Sirdey, for a manga or anime to gain popularity in France, it is necessary for a French translation to be published. Meanwhile in the United States, the information does not need to go through legal channels. It may be exchanged over the internet and an anime may become popular before an English version is formally produced.

Perez points out, "While there is a growing anime audience, there are also more people watching illegal media for free, which is also becoming an issue."

On the other hand, Fukuoka says, "The internet plays a major role in the spread of anime. There's an online community, and once someone uploads an anime on the internet, it gets subtitled in a day or two. Social networks may wield more power over the trend simply because it is not mainstream."

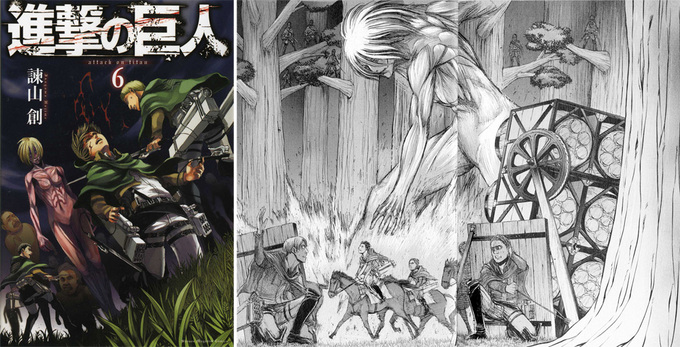

Though the major works mentioned earlier are outstanding favorites abroad, it may not be long before pieces currently popular in Japan such as Shingeki no Kyojin , Puella Magi Madoka Magica or From Me to You: Kimi ni Todoke win favor in the United States also.

So why has Japanese anime been accepted so vigorously overseas? When Fukuoka visited the Baltimore Otakon, he asked an African-American woman, a huge fan of NANA.

"She said there's a surprising lack of entertainment designed for women in the United States. NANA may be set in Japan, but it's a success story about a woman from a small town making her dreams come true in the city. It has many elements that can be universally understood, such as the friendship between women and falling in love."

Perez says, "The greatest difference with American comics is that Japanese manga and anime appeal to both adults and children. While the animation element is attractive to children, there's also a storyline and action for grown-ups to enjoy."

What does the anime convention crowd anticipate for the future?

Kelts predicts, "What we foresee now is American film studios taking notice of Japanese anime and teaming up with Japanese anime creators like Hayao Miyazaki. We may get to see joint productions by Japan and the United States."

Perez comments, "We hope the convention grows more popular without compromising quality. We want to ensure an enjoyable experience for our visitors, and hope the convention will develop as an attractive prospect for corporations also."

Sirdey, organizer of Japan Expo, an event that distinguishes itself from other conventions by also covering fashion, music, food, and other various aspects, says, "Most of the Japan Expo visitors are anime fans, but many are also people who have discovered Japanese culture through anime and want to learn more about Japan. One of our goals is to get people more interested in Japanese culture outside of anime."

Roland Kelts

Roland Kelts

Born to an American father and Japanese mother, he spent his childhood both in the United States and Japan. After graduating from Oberlin College and Columbia University, he has been lecturer at New York University, Rutgers University, Barnard College, and others. Kelts writes articles for Playboy, Salon, The Village Voice, Cosmopolitan, Vogue and other magazines and newspapers in the United States. He currently divides his time between Tokyo and New York. Author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the US. http://japanamerica.blogspot.com/

Thomas Sirdey

Thomas Sirdey

Born 1979 in France. He graduated from a business school and joined a music publisher. Sirdey founded Japan Expo with several partners and was an integral part in realizing the first event in 2000. He founded manga publisher Taïfu Comics in 2004, and pop culture event Comic Con' Paris in 2009. Sirdey is currently the Vice President of Japan Expo. http://www.japan-expo.com/

Marc Perez

Marc Perez

Joined an anime club influenced by friends at university, and became a fan reading Cowboy Bebop. He became a volunteer at the 2002 Anime Expo, joined the staff in 2004, and in 2007 was welcomed to the Board of Directors of the Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation (SPJA), the organizer of Anime Expo. Perez became its CEO in 2009, stepped down in 2010, but was back again in 2011. http://www.spja.org/

Toshihiro Fukuoka

Toshihiro Fukuoka

Born 1957. He joined ASCII (currently ASCII Media Works) in 1989 and became Chief Editor of the computer magazine EYE・COM in 1992. Fukuoka is currently Chief Editor of Weekly ASCII and Tokyo Kawaii Magazine, an iPhone magazine app for readers overseas. In 2011, he made a guest appearance at the Anime Expo with Hatsune Miku, supported by the Japan Foundation.

Keywords

- Anime/Manga

- Fashion

- Pop Culture

- Film

- Music

- International Exhibition

- Japanese Studies

- Cultural Policy/Public Diplomacy

- China

- Japan

- Viet Nam

- India

- United States

- Brazil

- Spain

- France

- Cosplay

- Manga

- Anime

- convention

- Japan Expo

- Anime Friends

- India Anime Convention

- Japan Anime Festival

- ACCtive Expo

- Roland Kelts

- Otaku

- New York Anime Festival

- Anime Expo

- Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation

- Marc Perez

- Thomas Sirdey

- Weekly ASCII

- Tokyo Kawaii Magazine

- Toshihiro Fukuoka

- Paris

- Barcelona

- Marseille

- New York

- Baltimore

- Los Angeles

- Comic Market

- Comiket

- Nagoya

- World Cosplay Summit

- Otakon

- Fullmetal Alchemist

- Haruki Murakami

- Crayon Shinchan

- Pokémon

- Hatsune Miku

- Hawaii

- Kawaii Kon

- NARUTO

- ONE PIECE

- BLEACH

- Hetalia: Axis Powers

- Salón del Manga

- Urusei Yatsura

- Shingeki no Kyojin

- From Me to You: Kimi ni Todoke

- NANA

- Hayao Miyazaki

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…