Hokusai in Full View Berlin 2011

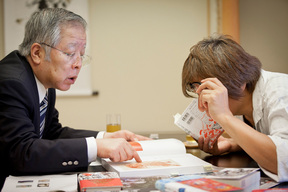

Seiji Nagata (Curator, Hokusai-Retrospective: The 150th Anniversary of Friendship between Japan and Germany)

Kotobuki Shiriagari (Manga artist)

Moderated by Tae Mori (Visual Arts Section, The Japan Foundation)

Cultural and commercial exchanges between Japan and Germany (Prussia at the time) began 150 years ago, in 1861, when a Treaty of Amity and Commerce was concluded between the two nations. It was the late Edo period in Japan and only some 10 years had elapsed since Hokusai, a genius ukiyo-e artist, had passed away (1760-1849). Back then, Hokusai's work was already influencing artists in Europe, and Japonism was beginning to spread its wings.

Today, Nagata Seiji, curator of the Hokusai retrospective in Berlin, and Shiriagari Kotobuki, a manga artist whose versatile comics are known both in Japan and around the world, will talk about the image of pre-modern Japan that Hokusai conveyed to the world and the power of his art that still captivates people today.

The German connection and Hokusai's popularity in Europe.

──I hear that among the series of events being held to mark 150 years of German-Japanese friendship, the Hokusai retrospective is drawing special interest.

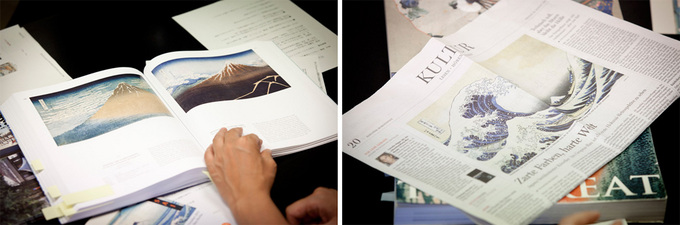

Exhibition at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin

Exhibition at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin

SHIRIAGARI: There are many other ukiyo-e artists. Why was Hokusai chosen?

NAGATA: Well, Hokusai is a favorite among many Germans, much more than we realize. If you look back on history, it was a German physician, Philipp Franz von Siebold, who first introduced Hokusai to Europe. He lived in Japan for a number of years from 1823, working as a resident doctor for the Dutch trading post. (Not many Japanese know that Siebold was German, not Dutch.) He was expelled from Japan for trying to take maps of Japan out of the country, which was an offense in those days. When he left, he took with him volumes of Hokusai Manga (Hokusai Sketches). He is believed to have once met Hokusai.

NAGATA: Well, Hokusai is a favorite among many Germans, much more than we realize. If you look back on history, it was a German physician, Philipp Franz von Siebold, who first introduced Hokusai to Europe. He lived in Japan for a number of years from 1823, working as a resident doctor for the Dutch trading post. (Not many Japanese know that Siebold was German, not Dutch.) He was expelled from Japan for trying to take maps of Japan out of the country, which was an offense in those days. When he left, he took with him volumes of Hokusai Manga (Hokusai Sketches). He is believed to have once met Hokusai.

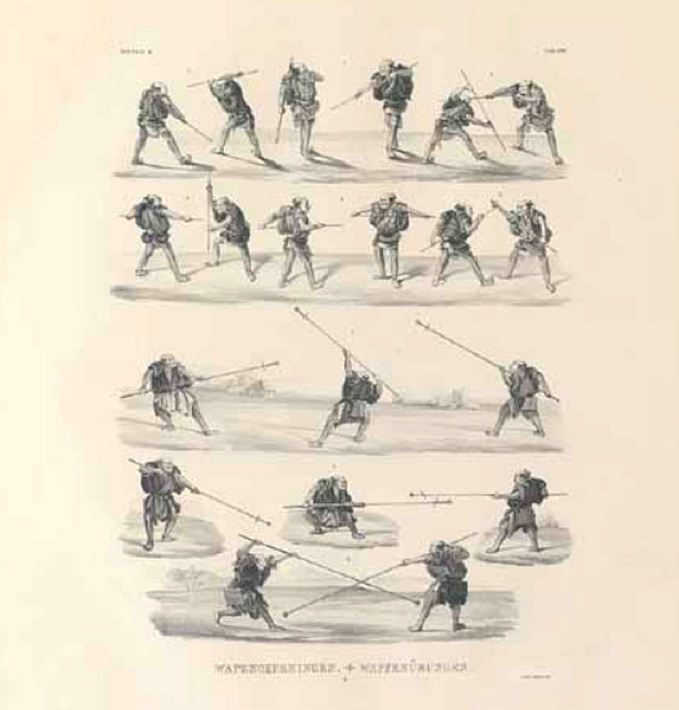

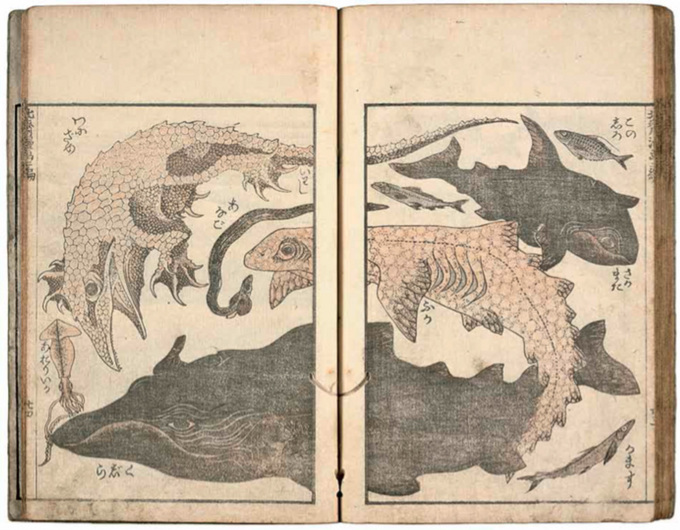

The 15 volumes of Hokusai Manga contain 3,900 sketches. Soon after returning to Europe, Siebold compiled his massive compendium Nippon (Japan), inserting many of Hokusai's illustrations.

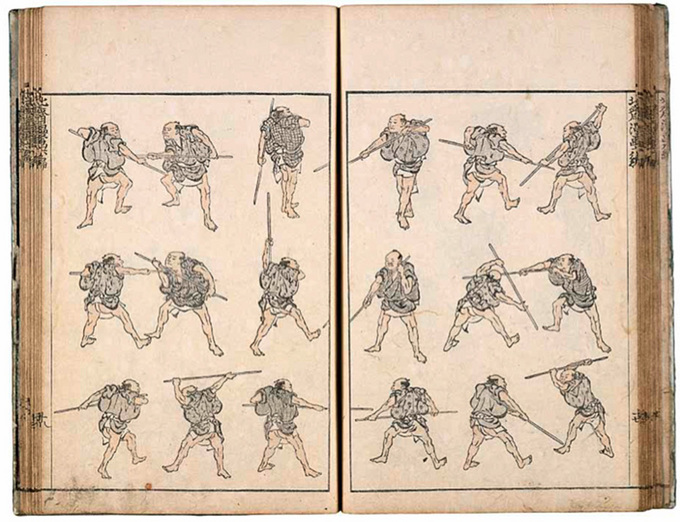

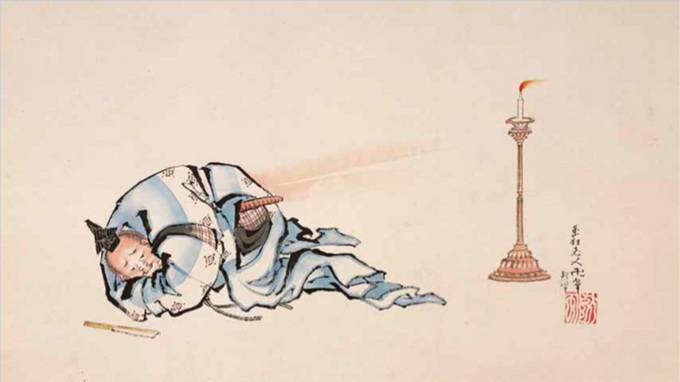

Denshin Kaishu Hokusai Manga Vol. 6

Denshin Kaishu Hokusai Manga Vol. 6

picture book, 1 vol

1817, New Year publication

Signature/Seal: Hokusai aratame Katsushika Taito/Fushinoyama

Publisher: Kadomaru-ya Jinsuke

Nippon

Nippon

1852

Writer & editor: Siebold, Philipp Franz Balthasar von

Collection: Boston University

A few years later, Japonism, which had influenced Impressionist painters in Paris in the latter half of the 19th century, swept across Europe. Two people were responsible for bringing ukiyo-e to the West and triggering this trend. One was a Japanese named Hayashi Tadamasa and the other was Siegfried Bing from Hamburg. Much later, Felix Tikotin, an art dealer in Germany in the 1940s and 50s, also added to the recognition by holding an exhibition of works by Rembrandt, Hokusai and Gogh in 1951 at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. He exhibited sketches by the artists, displaying them side by side. So it was the Germans who helped raise Hokusai's popularity in Europe.

SHIRIAGARI: It's my impression that Germans prefer graphic-design types of work, like Bauhaus, rather than classical ones, and I think Hokusai's work has a bit of the design aspect in them. I mean, especially, in the composition.

NAGATA: The German President came to the Hokusai-Retrospective and seemed to enjoy the works very much. He took his time moving from one exhibit to the next and said that he would visit again, not having had time to see everything. Hokusai's art is appreciated in Germany, much more than we realize.

Hokusai relocated 93 times and changed his name 30 times in his 70-year career.

──Could you tell us what is special about this Hokusai exhibition?

NAGATA: Hokusai's work can be divided into roughly 6 periods. In the exhibit, works from each period are displayed so that visitors can see the differences and the scale of his output.

SHIRIAGARI: So you are exhibiting works from each of the periods. He lived until he was almost 90 years old. So, how many pieces did he create throughout his lifetime?

SHIRIAGARI: So you are exhibiting works from each of the periods. He lived until he was almost 90 years old. So, how many pieces did he create throughout his lifetime?

NAGATA: I've been asked that many times, but we don't know. He must have worked every day, so there must be far more than we imagine. Sumida City in Tokyo, where Hokusai was born and lived, was devastated by major earthquakes in 1855 and 1923, and the bombings of World War II, so many of his works were destroyed. We just don't know how many survived.

SHIRIAGARI: It must have been difficult to select the 400 pieces from the tens of thousands of works left.

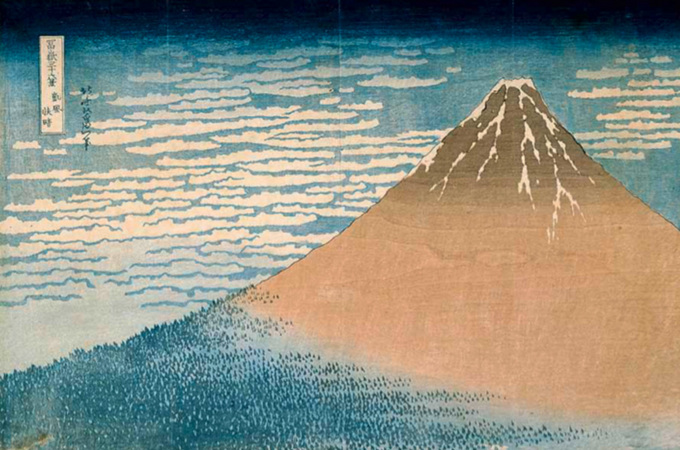

NAGATA: Major exhibitions of Hokusai's works have been held in Europe before, but, as in Japan, only pieces like Red Fuji, The Great Wave off Kanagawa and Hokusai Manga have become well known.

The famous Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series, which includes the Red Fuji and the Great Wave, was produced in 5 or so years when Hokusai was in his 70s. He also drew the Hokusai Manga series in this very short period.

Gaifu Kaisei (A Mild Breeze on a Fine Day)

Gaifu Kaisei (A Mild Breeze on a Fine Day)

Series: Fugaku sanjurokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji)

Oban, woodblock 26.3 x 38.6cm

ca.1831

Signature/Seal: Hokusai aratame Iitsu

Publisher: Nishimura-ya Yohachi

Collection: Katsushika Hokusai Museum of Art

Denshin Kaishu Hokusai Manga Vol. 2

Denshin Kaishu Hokusai Manga Vol. 2

picture book, 1 vol

the 4th month, 1815

Signature/Seal: Hokusai aratame Katsuhika Taito/Fushinoyama

Publisher: Kadomaru-ya Jinsuke

Hokusai made his debut as an artist when he was 20 years old and worked for 70 years until his death at around the age of 90. He was always pursuing new things. So in this exhibition we wanted to highlight the variety of his work--from his youth to just before his death.

When you compare the works from the various periods, they are so diverse that you might think they were created by different artists. Every time he tried something new, he changed his name. He used about 30 names in all. He called himself Hokusai for a short while only.

He also moved 93 times in his lifetime, always in search of new ideas. He never ceased to take in the new and cast off the old.

SHIRIAGARI: Which is his earliest work in the exhibition?

NAGATA: In his early years, he called himself Shunro and was a pupil of Katsukawa Shunsho. Shunsho drew portraits of actors, and Hokusai's debut work looked exactly like his teacher's.

SHIRIAGARI: Those portraits were like the stills of popular actors that fans collect today.

NAGATA: This is a portrait of Segawa Kikunojo. Beautiful, but in fact a male actor.

SHIRIAGARI: So Hokusai's career started with portraits, but what was he doing in his later years?

(Left) The Actor Segawa Kikunojo III as the Daughter of Masamune, Oren

(Left) The Actor Segawa Kikunojo III as the Daughter of Masamune, Oren

Hosoban, woodblock 30.3 x 13.7cm

1779

Signature/Seal: Katsukawa Shunro ga

Publisher: Unidentified

(Right) Sekiheki no Soso (Cao Cao before the Battle of Red Cliffs)

hanging scroll, ink and color on silk 115.0 x 34.2cm

the 8th month, 1847

Signature/Seal: Hachijuhachi-ro Manji hitsu/Hyaku

Collection: Katsushika Hokusai Museum of Art

NAGATA: He produced very few prints towards the end, but when you look at a piece he did when he was 88 years old, you can see that it's more brilliant and colorful than his earlier works. His works get more gorgeous as the years pass by.

SHIRIAGARI: Most people wither with age, but he seems to have flourished.

NAGATA: Yes, he even tried Western-style painting in his latter days. I would say his work had less vivacity in his younger days.

SHIRIAGARI: I see he made use of gradation in his work, but he used mineral pigments, didn't he?

NAGATA: Yes, he did. His drawings, prints, all of the work he produced in his later years look more alive than his earlier pieces. The one that really amazes me is Poppies. The flowers look as though they are swaying in the wind with the blue sky in the background. If it weren't for the Japanese writing, I would think it was the work of a Western artist or someone living in modern times. This painting would look nice framed in the Western style. Hokusai produced this when he was around 75 years old. He must have been quite something at that age.

We know that he started oil painting towards the end of his career. He was 75 when he talked about living till he was well over 100 so that he could change the art world -- he was determined to do that.

Keshi (Poppies)

Keshi (Poppies)

Oban, woodblock

ca.1833-1835

Signature: Sakino Hokusai Iitsu hitsu

Publisher: Nishimura-ya Yohachi

Collection: Sumida City

SHIRIAGARI: You can see he managed all the fine details even when he was in his 80s. Did he have good eye sight?

NAGATA: He wrote on one picture he produced when he was 89 that he didn't need glasses.

SHIRIAGARI: He had to say that! He was really playful!

Hokusai and today's manga artists have the same mindset.

──When a print of the Great Wave was actually reproduced live at the exhibition, we saw that as the colors were laid, there came a moment when the colors become visible from behind the sheet. The visitors all gasped in surprise when that moment came. It was delightful and made me realize that Germany is a country of meisters.

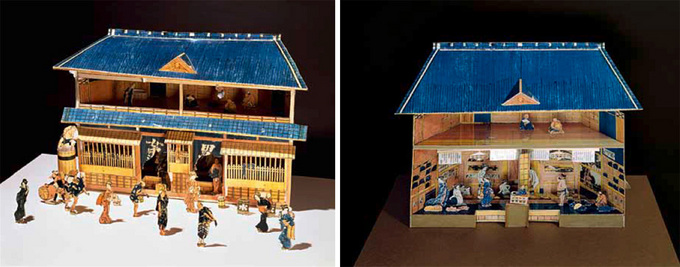

NAGATA: We devised many ways to display the works. Rather like the giveaways that come with children's magazines today, some of Hokusai's works can be made into three dimensional models by cutting out, folding and pasting the pieces together. I wanted to show this to our German visitors - that was how the works were meant to be enjoyed. The visitors were really amazed.

SHIRIAGARI: So this is a scale model of a bathhouse. Oh, he even has naked people inside!

Shinpan kumiage toro yuya shinmise no zu (A Set of Five Cut-out Pictures of a Newly Rebuilt Bathhouse)

Shinpan kumiage toro yuya shinmise no zu (A Set of Five Cut-out Pictures of a Newly Rebuilt Bathhouse)

Oban, woodblock 5 pieces/25.1 x 37.7cm each

ca. 1807-1812

Signature: Hokusai

Publisher: Maru-ya Bunuemon

Collection: Katsushika Hokusai Museum of Art

NAGATA: It's very well made with all the fine details. On the upper floor there's a space where the bathers can relax and cool down. If you look at it head on, you can see he's made it in perspective.

SHIRIAGARI: Yes, the model narrows towards the back.

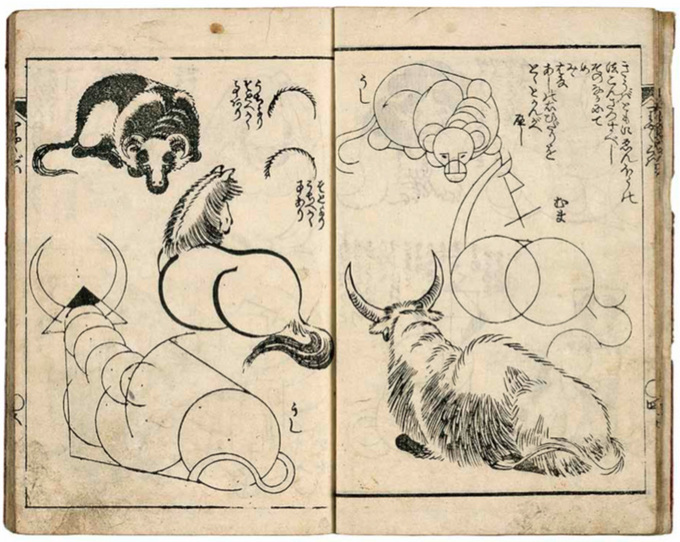

NAGATA: Hokusai was good at this sort of thing. You can't say that for every painter. He was more of a scientist than an artist; he liked to work with geometrical elements.

SHIRIAGARI: He reminds me of Leonardo da Vinci.

NAGATA: You're right. Some people call him the Japanese da Vinci. Hokusai said you can use a pair of compasses and a ruler to draw the skeletal structure of a thing. He shows in his book how to teach children to draw a cow using compasses.

Ryakuga haya-oshie (Quick Guide to Drawing)

Ryakuga haya-oshie (Quick Guide to Drawing)

picture book, 1 vol

1812, New Year publication

Signature: None

Publisher: Tsuru-ya Kinsuke

Collection: Katsushika Hokusai Museum of Art

SHIRIAGARI: I didn't know they had compasses back then! His work often looks elusive and I thought he was eccentric, just following his instincts, but I see now that he was more of a scientist.

NAGATA: Yes. It's about time people learned to appreciate the real Hokusai. We Japanese are not fully aware of his true talents.

SHIRIAGARI: Like one of his names, Gakyojin (a man mad about art), people liked his unpredictability.

NAGATA: You mean his capricious nature.

SHIRIAGARI: His picture of an octopus made me think he was really wacky. But on the contrary, it seems he was a sensible man.

NAGATA: As you say, he was actually a sound, responsible man. He knew how to joke around though. He loved humorous Senryu poems and composed many. Some were vulgar and erotic, but that's how he was.

There is a sketch of a man doing his business in a public toilet. That picture must have caused a commotion back then.

SHIRIAGARI: Well, somebody had to show how a samurai did it or nobody would know. It even shows the samurai's attendants waiting nearby, pinching their noses. It really must have stunk!

──Hokusai also drew many pictures of people breaking wind, didn't he?

NAGATA: He drew them when he was 80 years old.

SHIRIAGARI: At 80!

Hohi-zu (Flatus)

Hohi-zu (Flatus)

hanging scroll, ink and color on paper 30.1 x 54.2 cm

1839

Signature/Seal: Gakyo rojin Manji hitsu, yowai hachiju

NAGATA: The two German lady inspectors at the museum were pointing to the illustration and laughing. The man in the picture is dressed like a samurai but I think he's really an actor in a show.

SHIRIAGARI: I love the way Hokusai is obsessed with drawing something so trivial. His spirit resembles that of manga artists today, putting enjoyment before artistic expression. We make fun of what people in general would consider indecent or marginal, something that is not worth noticing. Our work is different from paintings that decorate major temples or mansions.

The talent to put images into patterns, drawings more real than the real thing

──It seems that Hokusai's work and today's manga have many things in common.

NAGATA: Hokusai Manga contains sketches to be used as models or samples by artists and craftsmen. If you cut out some of the illustrations of people and move them, they really look as though they are in motion.

SHIRIAGARI: Like an animation.

NAGATA: I know he would have done something amazing if he was living in our time.

SHIRIAGARI: He would probably have made 3-D games using computer graphics.

NAGATA: A game called the Great Wave, maybe?

SHIRIAGARI: Something like that, for sure. Hokusai had speed, too. Manga artists are quick, like him. We have to be because manga magazines are weekly publications. We don't use color and we simplify the drawings to save time. Another way to shorten the time is to have a certain illustration which has a meaning that the readers understand. So when a situation is repeated in a story, we use the same illustration, and the readers will know what it means.

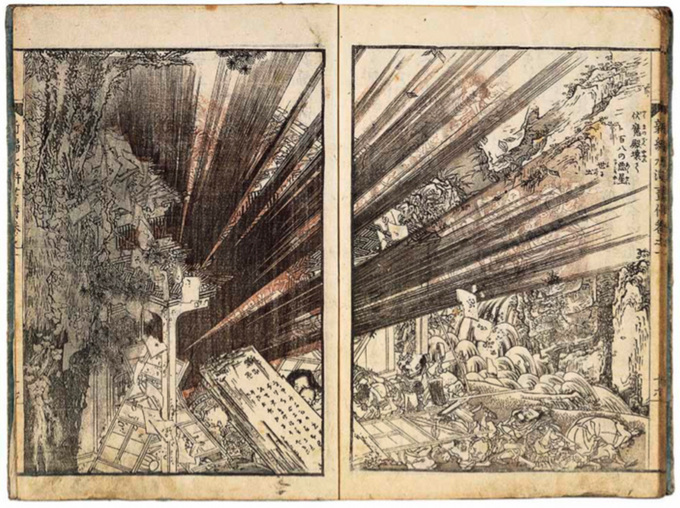

NAGATA: Yes, it's the same with Hokusai. With his woodblock prints, we see some of them have paint blotches in the margin -- he must have been in a real hurry. Many of his works resemble today's realistic comics called Gekiga. Hokusai's depiction of a long historical novel, Water Margin, was a Gekiga. There's a scene where demons and evil spirits burst out of a door which people had been forbidden to open and you can even see the air gushing out.

Shinpen suiko gaden shohen shochitsu (Illustrated New Edition of Suikoden, the first part)

Shinpen suiko gaden shohen shochitsu (Illustrated New Edition of Suikoden, the first part)

Yomibon, 6 vols

the 9th month, 1805

Signatures/Seal: Kyokutei Bakin saku (author), Katsushika Hokusai ga/Gakyojin (artist)

Publisher: Kadomaru-ya Jinsuke

Collection: Katsushika Hokusai Museum of Art

SHIRIAGARI: I remember seeing a scene like that in an Indiana Jones movie. Hokusai's illustrations are really something.

NAGATA: Illustrations like this may be common today, but not in those days. There are other Hokusai drawings with air and bricks exploding.

SHIRIAGARI: He also came up with the two-frame manga. In the Hokusai Manga, there are two-frame manga called Tate (vertical) and Yoko (horizontal). Between the two frames, time passes and a story unfolds.

NAGATA: They were a precursor of the current two-frame comics. The stories develop quickly and the drawings are really comical.

SHIRIAGARI: It amazes me how good he is. He doesn't practice or anything. He simply draws a line or object in one go--he doesn't need erasers.

NAGATA: But when we examine his rough sketches, we see that he really worked hard to achieve what he wanted.

SHIRIAGARI: I'm relieved to hear that. I thought Hokusai and Osamu Tezuka were the only ones who didn't need to make rough sketches.

NAGATA: Many manga artists are fans of Hokusai, aren't they? Like Sugiura Hinako and before that, Nemoto Susumu, the author of Kuri-chan.

SHIRIAGARI: Hokusai left us good examples to learn from. When we're working on a manga, we create samples of the characters so that our assistants can draw them just like us. And other manga artists can also learn the technique from those samples.

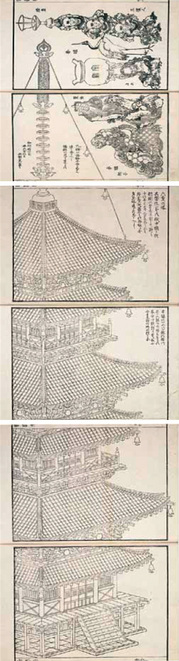

NAGATA: This book of illustrations is titled Shoshoku ehon shin hinagata (New Designs for Craftsmen). When you string together the pages, a pagoda appears. He has structural diagrams of temple bells and bridges, and also explains how to calculate the pitch of the roof.

Shoshoku ehon shin-hinagata (New Designs for Craftsmen)

picture book, 1 vol.

1836

Signature: Yowai Shichijushichi Sakino Hokusai Iitsu aratame Gakyo rojin Manji

Seal: Shape of Mt. Fuji

Publisher: Suhara-ya Mohei

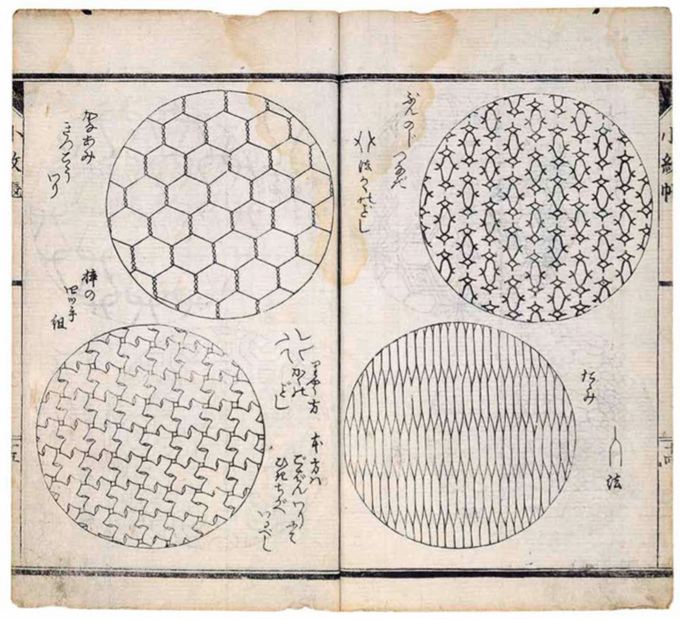

In Ehon saishiki tsu, he also describes how to paint in oil, which was a mystery at that time, and how to make copperplate prints. And he has created sample patterns for dyeing and weaving textiles.

SHIRIAGARI: It's a collection of design patterns.

NAGATA: Yes, it is. He even designed everyday things like wire netting and Tatami mats. Through his eyes, ordinary things became special.

Shingata komoncho (New Models for Kimono Patterns)

Shingata komoncho (New Models for Kimono Patterns)

picturebook 1 vol.

the 3rd month, 1824 (unconfirmed)

Signature: Sakino Hokusai Iitsu hitsu

Publisher: Ozaka-ya Shuhachi

SHIRIAGARI: He had a talent for turning things into patterns. You know that real waves are not like the waves he drew for the famous Great Wave print.

Kanagawa oki namiura (The Great Wave off Kanagawa)

Kanagawa oki namiura (The Great Wave off Kanagawa)

Series: Fugaku sanjurokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji)

Oban, woodblock 25.2 x 37.6cm

ca.1831

Signature: Hokusai aratame Iitsu hitsu

Publisher: Nishimura-ya Yohachi

Collection: Sumida City

NAGATA: That's right. But if you draw waves just as you see them, they will lack presence.

SHIRIAGARI: His are more real than the real waves. It teaches you that when you want to express something on paper, you cannot convey the true qualities just by drawing the object as you see it. I guess the essence of an object is expressed by capturing the patterns in the drawing.

NAGATA: That's what's fascinating about Hokusai.

Hokusai had an urge to draw everything he saw.

NAGATA: Hokusai's output was amazingly diverse. He has a collection of hundreds of sketches drawn with a single stroke of the brush, or pictures made with the 48 letters of the Japanese Hiragana syllabary. Those works were on display at the exhibition and really impressed the visitors. Drawings and sketches are highly valued in Europe and Hokusai's drawings are what tell you how good he was. So I brought a few to Berlin for the exhibit.

NAGATA: Hokusai's output was amazingly diverse. He has a collection of hundreds of sketches drawn with a single stroke of the brush, or pictures made with the 48 letters of the Japanese Hiragana syllabary. Those works were on display at the exhibition and really impressed the visitors. Drawings and sketches are highly valued in Europe and Hokusai's drawings are what tell you how good he was. So I brought a few to Berlin for the exhibit.

SHIRIAGARI: I guess he had to draw everything he saw.

NAGATA: His work covers a really wide range and they can be classified into six categories. So studying Hokusai is like studying six artists.

SHIRIAGARI: So you need to make a six-fold effort if you want to understand him. The Japanese poet Tanikawa Shuntaro has written an enormous number of poems. In the afterword for a collection of his works, I wrote that he has the ability to express all things poetically and mass produce them like a factory. The same can be said about Hokusai. He churned out one piece after another, drawing every idea that came to mind and everything that he saw. He was really something.

NAGATA: Craftsmen back then would have had to pay a fortune to have a famous artist draw a design for their work. That's why woodblock prints made it easy for craftsmen to get the design they wanted. Work memoranda kept by craftsmen who made sword guards had clippings of Hokusai's sketches pasted in them. The clippings had needle holes, which meant that the samples were cut out and pinned on a piece they were working on. That's why not many of his works remain.

SHIRIAGARI: We manga artists use design and pattern collections, too.

NAGATA: Hokusai Manga was a collection of 3,900 sketches -- that must have been helped the craftsmen.

SHIRIAGARI: You might as well call it a reference book of illustrations and designs.

NAGATA: Hokusai Manga must have been very useful when Siebold compiled his encyclopedic Nippon. You know, not many people remember what a public toilet looked like, and ukiyo-e only depicted pretty things.

SHIRIAGARI: Did ordinary people buy Hokusai Manga out of curiosity?

NAGATA: Not only ordinary people: some were found in the graves of feudal lords. The books were woodblock prints and they are still published today using offset printing--it's probably the longest selling collection of illustrations in Japan.

SHIRIAGARI: I wonder what career he would have pursued if he lived in our time. He did commercial designs, decorations, patterns, drawings, comic books and was also a publisher. A first edition of any of his works would probably have sold 3 million copies, like the very popular One Piece comic series in Japan. But artists in those days weren't paid royalty, were they?

SHIRIAGARI: I wonder what career he would have pursued if he lived in our time. He did commercial designs, decorations, patterns, drawings, comic books and was also a publisher. A first edition of any of his works would probably have sold 3 million copies, like the very popular One Piece comic series in Japan. But artists in those days weren't paid royalty, were they?

NAGATA: No they weren't. Once you submitted a work that was it. The artist would never know if it was sold to another for a better price. So they lived in poverty all their lives.

SHIRIAGARI: I'm envious of his ingenuity. How could he come up with one idea after another like that?

NAGATA: Hokusai lived till he was almost 90 years old, at a time when the average life span was just 50, so he was no average person. I'm sure he wasn't interested in social status, but back then, ukiyo-e artists were treated as run-of-the-mill painters and not recognized as artists. Painters and illustrators who were hired by the feudal government were recognized as artists. Ordinary painters were ranked at the same level as tatami-mat craftsmen or artisans who mended screens.

SHIRIAGARI: So Hokusai was considered an artisan.

NAGATA: Yes. He could have worked for the government, but he chose to be free and create whatever he pleased. He was so poor he couldn't even afford a desk, so he made do with a wooden box. He drew or painted from morning to night, till his hands hurt and he couldn't continue any more. He would eat noodles and go to bed and then wake up the following morning to start drawing again. Every day was a repetition of that pattern.

Misunderstandings may create a new culture.

──I think Hokusai was instrumental in promoting cultural exchange. Back then Japan had cut itself off from the rest of the world and only a limited amount of information was available. But he tried to learn as much as he could by talking to people who knew and studying foreign artifacts. As a result, for instance, he adopted perspective and attempted to incorporate the alphabet in his pictures.

──I think Hokusai was instrumental in promoting cultural exchange. Back then Japan had cut itself off from the rest of the world and only a limited amount of information was available. But he tried to learn as much as he could by talking to people who knew and studying foreign artifacts. As a result, for instance, he adopted perspective and attempted to incorporate the alphabet in his pictures.

SHIRIAGARI: Perhaps Japan should go into isolation once again and in 100 years it may have developed a new culture. But the world is so closely connected these days, cultures are losing their individuality.

──But on the other hand, cultural exchange has brought Hokusai to Europe, inspiring many artists. The same thing happened, recently, when cosplay was introduced to Europe. When Japanese culture is brought to foreign countries unaltered, a very curious phenomenon occurs sometimes. So choosing between isolation and exchange is difficult, don't you think?

NAGATA: Confusion does occur when people come into contact with an alien culture. It happened when Japonism was all the rage in Europe: people enthused over a black porcelain decorated with gold, but it turned out that the gold was used to glue pieces of broken porcelain together. Even Hokusai's Red Fuji may have been the result of his attempt to economize on the number of woodblocks he used. But sometimes we gain from these misunderstandings.

SHIRIAGARI: You're right. From time to time, a masterpiece is the result of a mistake or inevitability. The state of the country a man lives in, or his circumstances, these are sometimes the elements that help create a unique work of art.

Freedom in work and life style

──In conclusion, could you tell us what your aim is in holding this exhibition? And what is Hokusai to the world or to the people living in this age?

NAGATA: A fellow curator once told me that he envied Hokusai because he was still an "active" artist. I asked him what he meant, and he told me that works by artists of the Kano school, who were the official artists of the Tokugawa government, are now antiques, but, you still see Hokusai's works on TV and other media--so in that sense, he is an "active" artist.

NAGATA: A fellow curator once told me that he envied Hokusai because he was still an "active" artist. I asked him what he meant, and he told me that works by artists of the Kano school, who were the official artists of the Tokugawa government, are now antiques, but, you still see Hokusai's works on TV and other media--so in that sense, he is an "active" artist.

His work is still relevant today. Today's artists integrate his pieces into their work and give them a new look --a modern version of Hokusai's art. His work has the potential to move forward.

When you think about his relevancy, I think Hokusai himself is the reason for that. I always tell young students that Hokusai was not the son of a rich man, nor did he ever become rich. But he worked untiringly, and that's why he became the best in the world.

When I speak to elderly people, I ask them to take a look at the Red Fuji. I remind them that Hokusai painted this when he was in his 70s. Hokusai said that he wanted to live to be well over 100 so he could reform the art world. I tell them that people today should not retire at 60 or 70, only to spend the remaining years like a recluse.

We can look to Hokusai to guide us on how to live in today's world. It would be splendid to live until you are over 100, doing something that you love and believe in. He tells us we should never give up; we should pursue whatever we have set our mind on doing. We should be grateful to have such a mentor.

I spoke about this in Germany, too. Both Hokusai's work and his lifestyle continue to attract people and their value still holds today. We can continue to learn from them. His art depicts his spirit and I want people to see that.

SHIRIAGARI: Any artist would envy him. He held on to his freedom to draw anything he pleased. Even from our age, we can see he was a free spirit.

Photos by Aikawa Ken-ichi

(Hokusai's works mentioned in the article were all displayed at the Hokusai-Retrospective marking 150 Years of German-Japanese Friendship)

Seiji Nagata

Seiji Nagata

Director of Katsushika Hokusai Museum of Art, Curator for Hokusai-Retrospective: The 150th Anniversary of Friendship between Japan and Germany.

Born in 1951 in Tsuwano, Shimane Prefecture, he first came across Hokusai while browsing in a secondhand bookstore and has been mesmerized ever since. He was vice director of the Ota Memorial Museum of Art before founding the Katsushika Hokusai Museum of Art in 1990. A leading authority on Hokusai, he has curated many Hokusai exhibitions around the world. He was a guest curator for the Hokusai Exhibition held in 2005 at the Tokyo National Museum and wrote the introduction to the catalogue. This exhibition went on to be held at the Sackler and Freer Galleries in Washington, D.C. and was a huge success both in the US and Japan. He has authored many books on Hokusai.

Nagata's works:

Motto shiritai Katsushika Hokusai--shogai to sakuhin [More about Katsushika Hokusai - his life and work]. Tokyo Bijutsu Inc., 2005.

Rekishi bunka raiburari (91) Katsushika Hokusai [Library of History and Culture Vol. 91 Katsushika Hokusai]. Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2000.

Nippon no ukiyo-e bijutsukan [Ukiyo-e Museums in Japan]. Kadokawa Group Publishing Co. Ltd., 1996.

Shiryo ni miru kindai ukiyo-e jijo [Looking at Ukiyo-e in Modern Times through Collected Materials]. Sansaisha, 1992.

Hokusai bijutsukan [The Hokusai Museum]. Shueisha Inc., 1990.

Kotobuki Shiriagari

Kotobuki Shiriagari

Manga Artist

Born in1958, Shizuoka, Japan. After studying graphic design at Tama Art University, he joined Kirin Brewery Company and worked in advertising and package designing. He made his debut as a manga artist with the series Ereki na haru (Electric Spring). His dark humor and social criticism in his works have established him as a new type of gag manga artist. Since leaving his job at Kirin and becoming a full-time artist in 1994, he has published many fantasy and literary manga, and has also expanded his area of work to writing essays, creating video images, computer games and various other art forms. His works include Ryusei kacho (Shooting Star Section Chief), Higeno OL Yabunai Sasako (Sasako Yabunai, the Bearded Female Office Worker), Chikyu boei ke no hitobito (The People of the Earth Defense Family), Koisomore-sensei (Our Teacher, Koisomore), Hakobune (The Ark). He received the 46th Bungeishunju Manga Award in 2000 and the 5thTezuka Osamu Cultural Prize Excellence Award in 2001. Mayonaka no Yaji-san, Kita-san (Yaji-san, Kita-san in the Dead of Night) was made into a movie starring Tomoya Nagase and Shichinosuke Nakamura and directed by Kankuro Kudo. He has been teaching at the School of Progressive Arts, Kobe Design University, since 2006. His work has been exhibited in France, Germany and Indonesia. His latest work, Anohi kara no manga (Manga from that Day On), written immediately after the major earthquake and tsunami hit northeast Japan in March 2011, has been often taken up by the media, drawing much attention.

Related Events

Keywords

- Anime/Manga

- Design

- Cultural Heritage

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- History

- International Exhibition

- Japanese Studies

- Cultural Policy/Public Diplomacy

- Japan

- Netherlands

- Germany

- Hokusai

- Berlin

- Seiji Nagata

- Kotobuki Shiriagari

- manga artist

- Edo

- ukiyo-e

- Europe

- Siebold

- Japonism

- Hayashi Tadamasa

- Siegfried Bing

- Felix Tikotin

- Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam

- Rembrandt

- Gogh

- Bauhaus

- Sumida City

- meisters

- da Vinci

- samurai

- animation

- Osamu Tezuka

- Sugiura Hinako

- Nemoto Susumu

- Drawings

- sketches

- Tanikawa Shuntaro

- ONE PIECE

- craftsmen

- different culture

- culture

- cosplay

- isolation

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…