Tabaimo on Venice Biennale: A Complete Report (Part II)

The Venice Biennale, held in Italy every two years, is the world's oldest and biggest art exhibition, "the Olympics" in the field of art. In 2011, a milestone year that marked the 150th anniversary of Italy's unification, the largest number of countries is participating in this exhibition of contemporary art. The venue is crowded as it has never been before. The artist in the Japanese Pavilion is Tabaimo. She is showcasing a giant installation that has turned the entire pavilion into one piece of art. In the September issue of Wochikochi Magazine, the top story is the complete report on the biennale she presented on August 9 following her return to Japan. Part I (released on September 5) carries a report on the exhibition by Tabaimo as well as by Yuka Uematsu, the curator at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, who serves as the commissioner of the Japanese Pavilion. In Part II, we have invited Kazuko Aono, who was in charge of the YOROYORON Tabaimo exhibition, to talk about what she and Tabaimo think of the work at the Japanese Pavilion and what is happening at the biennale.

Creating midnight sea after overcoming many challenges

AONO: The Hara Museum of Contemporary Art invited Tabaimo for the first time in 2003 when she held the solo exhibition Tabaimo - yumechigae in Hara Museum ARC (Gunma). In 2006, she held another one-person show, YOROYORON Tabaimo, at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art and I was fortunate enough to curate it.

AONO: The Hara Museum of Contemporary Art invited Tabaimo for the first time in 2003 when she held the solo exhibition Tabaimo - yumechigae in Hara Museum ARC (Gunma). In 2006, she held another one-person show, YOROYORON Tabaimo, at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art and I was fortunate enough to curate it.

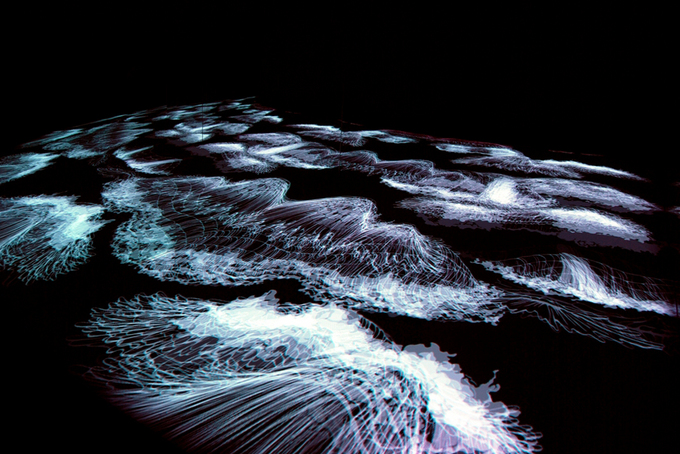

In Part I, Tabaimo gave us explanations about mirrors. As I remember, she made full use of them for the first time in her work midnight sea, which she first introduced at the time of the YOROYORON Tabaimo exhibition and re-exhibited at Hara Museum ARC. The exhibition used the stairwell inside the museum and visitors could look down on it from the second-floor balcony. Her work made effective use of the special space in the museum and we bought it after advising Tabaimo that it might be difficult to recreate the same kind of exhibition. Later, in 2008, we decided to exhibit midnight sea again when Hara Museum ARC reopened after renovation and I talked about this plan with Tabaimo.

It was on this occasion that she came up with the idea of using mirrors. Isn't that right?

TABAIMO: Yes, that's correct. I used mirrors for the first time at the Hara Museum ARC exhibition. My works change depending on the space they are given and they come really alive once they find the kind of space that's good for them. The Hara Museum ARC exhibition is one of the best examples.

At that time we had problems about the size of mirrors and also about whether there was enough time for me to create the work. I wasn't sure if we would be able to hold the show--whether we would be able to keep the mirrors standing upright and whether we would be able to project the images accurately on the mirrors. We didn't know what would happen on these two issues until we actually put the exhibition together. In addition, mirrors are fragile and easy to break and you can't relax during exhibitions. midnight sea was created after we overcame many challenges. I am really grateful for what Ms. Aono and the museum staff did.

AONO: Well, I am sure we are the ones who have to say "thank you" for allowing us to show your wonderful work. midnight sea is still on display at Hara Museum ARC, so I hope you will all go and see it.

And the use of mirrors has been inherited in the works you displayed at the DANMEN exhibition (showing BLOW and chigirechigire) at the Yokohama Museum of Art and the National Museum of Art, Osaka, and now at the Venice Biennale.

midnight sea (2006)

midnight sea (2006)

Possession of the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art/c Tabaimo

YOROYORON Tabaimo Exhibition: Poster (left), Flyer (right)

Courtesy of the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art/Design Masayoshi Nakajo

Maintenance is impossible without adjustment to accuracy of less than 1 millimeter

AONO: Now, we'd like to ask Ms. Uematsu about the Venice Biennale. What did you think when Tabaimo came up with the idea to turn the entire Japanese Pavilion into one installation of her work?

UEMATSU: The first thing I thought was, "OK. That's the way she wants to get it done!" Having seen past Japanese Pavilion exhibitions, I was well aware of the difficulty of using that space. I was hugely impressed by her idea.

UEMATSU: The first thing I thought was, "OK. That's the way she wants to get it done!" Having seen past Japanese Pavilion exhibitions, I was well aware of the difficulty of using that space. I was hugely impressed by her idea.

At that time, I was involved in preparations for the Tabaimo: DANMEN exhibition at the National Museum of Art and I was watching a wonderful space design being created right before my eyes. So, I was really looking forward to finding out what sort of exhibition it was going to be in Venice, which is probably one of the great joys reserved for curators.

In 2007, Tabaimo's works were shown also in the Italian Pavilion in the Venice Biennale. So I thought a simple exhibition using one screen, just like in 2007, would be a possibility. Instead, she came up with a plan that would run straight into a daunting challenge?how to use the space at the Japanese Pavilion. I was also thrilled about the idea, "Is the world of a frog living in a well really so small?" I couldn't wait to see what sort of world was going to emerge.

AONO: I was enormously impressed. I almost sighed with admiration, finding how so beautifully the Japanese Pavilion was transformed. The hardship the two people went through is beyond all imagination. The exhibition is going to continue through November 27 of this year, and I imagine it's really hard to maintain the quality of your work. What do you think?

TABAIMO: Before dealing with the issue of space, I already knew I would use projectors. I also wanted to use the exterior of the building, so I was reasonably prepared to face maintenance trouble. Since exhibitions are usually held inside museums and art galleries, this was a problem on a slightly different level.

TABAIMO: Before dealing with the issue of space, I already knew I would use projectors. I also wanted to use the exterior of the building, so I was reasonably prepared to face maintenance trouble. Since exhibitions are usually held inside museums and art galleries, this was a problem on a slightly different level.

Quality maintenance is extremely difficult in overseas exhibitions. People rarely understand the level of maintenance we require. That makes it necessary for a curator to be aware of the importance of quality and also to make the technical staff understand it as well. Complete coordination among the staff is important. In that sense, the exhibition at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art was just perfect. That's the kind of quality I wanted to aim at this time around.

AONO: I hear you had a great staff this time. They are still managing the maintenance of your work in Venice?

TABAIMO: That's right. They understand the best condition for my work probably better than I do. They have been closely involved from the beginning of installation and they are ready to deal with any trouble perfectly.

At the beginning, I thought it would be enough to do maintenance once every two months. But the dust at the Giardini was worse than I had imagined. Even one or two people walking through the park kick up dust. That, of course, does considerable damage to the projectors installed outside, and even to those inside the pavilion. Now I am asking them to do maintenance once a week. I had no idea I would have to ask them to handle this sort of major work. I guess I didn't think about this problem seriously enough beforehand. I had held some exhibitions using projectors in the past, but the environment was surprisingly different this time. The projectors are easily broken when dust gets in, but museum staffs do a great job keeping them in shape. When an exhibition continues for a long time, we have to change the electric bulbs because the brightness of light from each projector becomes uneven. Even in those cases, however, I can comfortably depend on museum people.

But I had never experienced an exhibition that goes on for six months. When I heard "six months," I thought I would have to get all the projectors changed at least after the first three months. I knew that unexpected problems would also crop up along the way. But the projectors deteriorated faster than I had imagined.

AONO: You are using 18 of them, and you also have to worry about DVD players and speakers.

TABAIMO: We can do all right with the players and speakers. But more than anything else, it's a big headache to keep the projectors in good working order. It's necessary to adjust their positions to the accuracy of less than one millimeter, which greatly influences the quality of the images. So it's impossible to handle the maintenance work unless you have a complete grip on an installation.

Works that break with the mainstream create new concepts

AONO: The artistic director of the Venice Biennale this time is Switzerland's Bice Curiger. The title she proposed was ILLUMInations. This title has a double meaning?"illumination" that symbolizes "light" and "enlightenment," on one hand, and "illuminated nations" that stresses the element of "nation," on the other. I thought it's very interesting that, at the Japanese Pavilion, we are using "Galapagos Syndrome" faced by Japan today as the key word.

AONO: The artistic director of the Venice Biennale this time is Switzerland's Bice Curiger. The title she proposed was ILLUMInations. This title has a double meaning?"illumination" that symbolizes "light" and "enlightenment," on one hand, and "illuminated nations" that stresses the element of "nation," on the other. I thought it's very interesting that, at the Japanese Pavilion, we are using "Galapagos Syndrome" faced by Japan today as the key word.

UEMATSU: The Japanese Pavilion announced details of its exhibition about two weeks before the biennale's title was made public, which was a strange coincidence. In the exhibition Curiger curated, the work of Venetian painter Tintoretto was playing a prominent role in the Italian Pavilion while that of James Turrell, known as the artist of light, was also on display. She was embracing history as well as light as a phenomenon.

The thing is that the expression "Beyond Galapagos" started coming out just about the time I was working on the concept of the exhibition. In press interviews, many people asked Tabaimo what exactly "Beyond Galapagos" means. But the title teleco-soup clearly defines her theme and work. We hit on that title while the two of us were tossing various ideas around.

AONO: teleco-soup has elements of word play and we can read many meanings into it. But wasn't it difficult to make Western people understand what such a uniquely Japanese expression means?

TABAIMO: teleco-soup and "telescope" sounds pretty much alike and I thought they would understand the connection between these two words.

I said before that it's important that tereco is a local word. I somehow can't bring myself to understand the artistic concepts of the West and create my works in accordance with them. I am well aware that Western concepts are important for contemporary art. Yet, I don't feel like adopting them as my own. This state of mind is also reflected on the word tereco. By moving in a "local" direction I wanted to express a world that inversely spreads outward.

I strongly felt in Venice that winning recognition for your work and Western artistic concepts are two different things. There is no doubt that modern art and Western concepts have progressed hand in hand. Critics have also created artistic ideas by studying Western works. But I think the creation of new concepts will become possible as the number of works that do not fit in with existing concepts continues to increase. The frog in the well doesn't always want to go see the ocean. There is also a possibility that this frog can continue digging in the ground at its feet, broaden its horizons and arrive at a universal concept.

AONO: What do you think, Ms. Uematsu?

AONO: What do you think, Ms. Uematsu?

UEMATSU: While I was talking with an English friend, he told me he knew that teleco-soup comes from the word telescope. I had a feeling that people understand such concepts as abekobe and ireko when they experience those art works. One of the characteristics of Tabaimo's works is that they have a persuasively convincing strength when we come face to face with them.

AONO: I hear Tabaimo visited Venice again at the end of July. What did you think this time, a while after the busy opening?

TABAIMO: Some people say there's nothing particularly unusual about this with the Venice biennale, but I was surprised to find that people think it's only natural that the conditions of the works on display begin deteriorating right from the time of vernissage (the opening period at the biennale when press representatives and people from the world of art gather).

At first, I thought the Swiss Pavilion was great, but then I found it left in a condition that would make it absolutely impossible to convey the intent of the artist. Only about a third of the entire Swiss exhibition was ready and the sort of images that held the key to the success of the whole show weren't on display. It would be very sad if the artist agreed to go ahead and open the exhibition in such a condition. In Part I, I talked about 50-50 responsibility. I consider viewers to be my important co-producers. For this very reason, I have to bring my works to the level which makes them want to maintain close relations with them when they see them. When you come right down to it, this is nothing but my own "local" rule. But if modern art itself abandoned the attempt to improve the quality of works, it would become nothing but a topic people bring up only when it's convenient.

Of course, there were pavilions that firmly continued to maintain the quality of works at the time of vernissage and went on with perfect exhibitions. But why is it that only one month makes such a difference? I think we have to consider the meaning of modern art and how it should be.

Condensed poison runs strong in the core of the trunk

AONO: At the end we'd like to take up some of the questions from the audience. Could you tell us if there were reactions to your work in Venice that still stick in your mind?

UEMATSU: Those people who are well-acquainted with Tabaimo's creative activity often compared her installation at the biennale with her works in the past. On the other hand, those who saw her work for the first time asked, "What is Tabaimo? Is that the name of the artist?"

AONO: Yes, it's hard to figure out from the name if the artist is a man or a woman.

UEMATSU: But everybody had the same reaction when they stepped inside the pavilion. They were surprised. They often went "Ah!" Some were puzzled at the strange space. But they appreciated her work in entirely different ways depending on where they stood. Many didn't feel like leaving even after they completed their tour of the exhibition. Especially this time, the installation was designed in such a way that it was difficult to understand it unless they stopped and thought for a while. So they were enjoying her work in their own different ways, locked in their own thoughts.

AONO: How about you, Tabaimo?

TABAIMO: Many of those familiar with my works said, "There's no 'poison' this time around." In my past works, if I compare them to a tree, I created branches and leaves, scattering details that are the equivalent of leaves here and there, and then extending the branches. I think these parts contain the poison. This time, however, I wanted to draw the part of the trunk. That may have made it difficult for people to understand the detailed explanations about the poison, or the kind of poison that was used.

TABAIMO: Many of those familiar with my works said, "There's no 'poison' this time around." In my past works, if I compare them to a tree, I created branches and leaves, scattering details that are the equivalent of leaves here and there, and then extending the branches. I think these parts contain the poison. This time, however, I wanted to draw the part of the trunk. That may have made it difficult for people to understand the detailed explanations about the poison, or the kind of poison that was used.

Nevertheless, the poison runs deep and strong in condensed form in the core of the trunk. People may not be able to see it, but it's definitely there.

UEMATSU: In that sense, Japanese Kitchen and Japanese Commuter Train have a clear sequence and it's easy to figure out what the poison is.

This time, however, it's sprinkled around as various metaphors and it may be difficult at first glance to understand what they mean. Put in a different way, different viewers can read entirely different stories into them.

TABAIMO: In the past I was often asked, "What does this motif mean?" But what I'd like to do is not to solve a riddle but to have people see how me and my works are related. There were far fewer people this time around who came up and asked me about the motif. I had a feeling that they were relating my work to themselves and experiencing it in a straightforward way.

AONO: That also has something to do with your artistic stance that viewers should have a 50% responsibility.

TABAIMO: Viewers slip into the images through the repetition of them and their reflections in the mirrors and become part of the work or the whole of the work. That process goes on forever. I think many people this time experienced this feeling as their own.

If you are going to Venice in the future, you should be able to see my work in what I consider to be 100% condition. I have been in touch with the local staff and I am trying everyday to maintain that condition. I am happy if you can enjoy my exhibition.

Photo: Kenichi Aikawa

JFIC Library Venice Biennale Catalog Exhibition In commemoration of the 54th Venice Biennale, the catalogs of works by Japanese artists who participated in the Japanese Pavilion exhibitions?from Kishin Shinoyama in the 37th exhibition in 1976 to Miwa Yanagi in the 53rd exhibition in 2009?are on display in the JFIC Library. You can look through the catalogs or check them out.

Date: September 5 (Mon.) - September 16 (Fri.), 10:00 - 19:00

Place: Japan Foundation JFIC Library (Yotsuya, Tokyo)

Venice Biennale Japanese Pavilion Exhibition press conference

Click here for a video clip of the press conference held in July 2010 (in Japanese)

Takeshi Art Beat on NHK, October 12, 2011

A report on the Venice Biennale with an appearance by artist Tabaimo.

Related Articles

Related Events

Keywords

- Design

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- International Exhibition

- Japan

- Italy

- Venice Biennale

- Hara Museum of Contemporary Art

- Tabaimo

- Yuka Uematsu

- Kazuko Aono

- The Japan Foundation

- Hara Museum ARC

- Yokohama Museum of Art

- National Museum of Art Osaka

- Giardini

- Bice Curiger

- Galapagos Syndrome

- Tintoretto

- James Turrell

Back Issues

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…