Japanese Product Design and Design in Asia

From 2008 to 2011, the exhibition WA: The Spirit of Harmony and Japanese Design Today was launched at the Japan Cultural Institute in Paris, after which it was shown in six cities in five countries: Budapest (Hungary), Essen (Germany), Warsaw (Poland), Saint Etienne (France), and Seoul (Korea). The exhibition, a systematic introduction to Japanese product design and the traditional culture on which it is based, was met with an overwhelming response in each country. Japanese designs are often intended to elicit renewed interest in traditional and regional skills and crafts, and to encourage communication between the manufacturer and the consumer. They go beyond the simple pursuit of material goods and contain hints towards a new system of production and consumption. The homecoming exhibition was held at the Musashino Art University Museum. To mark the occasion, a talk event was held with three experts, Noriko Kawakami, one of the curators of the WA exhibition, designer Takashi Ashitomi, involved for many years in a project to revive local industries in Japan, and design producer Hoyumi Yuasa, who has worked with designers in Europe and Asia. They discussed the innovative efforts by Japanese and Asian designers and their perspectives on the future.

Japanese Design Created in Collaboration with Artisans

KAWAKAMI: The WA exhibition, which opened on June 24, has harmony as its keyword. The word emerged in a brainstorming session by the curator team consisting of Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Masafumi Fukagawa, Shu Hagiwara, and myself during the initial stages of planning. Japanese design is characterized by the integration and harmonization of elements that at first glance do not mesh with each other, such as traditional arts and crafts with cutting-edge technology or designs with Japanese and European cultural attributes. Although this Japanese trait has been influenced by recent trends, network development, and associations with other countries, it is the concept of WA, or the spirit of harmony, which acts as its catalyst; and that is the theme of this exhibition shown through the design of everyday products.

KAWAKAMI: The WA exhibition, which opened on June 24, has harmony as its keyword. The word emerged in a brainstorming session by the curator team consisting of Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Masafumi Fukagawa, Shu Hagiwara, and myself during the initial stages of planning. Japanese design is characterized by the integration and harmonization of elements that at first glance do not mesh with each other, such as traditional arts and crafts with cutting-edge technology or designs with Japanese and European cultural attributes. Although this Japanese trait has been influenced by recent trends, network development, and associations with other countries, it is the concept of WA, or the spirit of harmony, which acts as its catalyst; and that is the theme of this exhibition shown through the design of everyday products.

The overseas response to the exhibition was varied; for example, in Korea it attracted much interest because the two countries are close in both geography and culture. Mr. Ashitomi gave a special lecture on that occasion, a very meaningful talk on the future of Japanese design. Can you fill us in on the content of the lecture?

ASHITOMI: My talk focused for the most part on my participation in a project to promote local industry in Takaoka City, Toyama Prefecture. Lacquer and metal-casting are the major industries of Takaoka City, having many skilled craftsmen of Buddhist ritual articles and tea ceremony utensils. When I first visited the city in 1999, their industry was in decline, and of the 600 small and medium manufacturers and factories, it was said that "a local company goes out of business every day." They called me in the hope that something could be done about this.

ASHITOMI: My talk focused for the most part on my participation in a project to promote local industry in Takaoka City, Toyama Prefecture. Lacquer and metal-casting are the major industries of Takaoka City, having many skilled craftsmen of Buddhist ritual articles and tea ceremony utensils. When I first visited the city in 1999, their industry was in decline, and of the 600 small and medium manufacturers and factories, it was said that "a local company goes out of business every day." They called me in the hope that something could be done about this.

I have always been an advocate of "high-tech" (cutting-edge technology), and I think that from a certain point of view the highly skilled craftsmen of traditional arts can also be called "high-tech". In metal-casting, for instance, there are specialists for each stage of the metal-casting process, such as for casting the metal, polishing it, and applying color, with each stage requiring a highly developed level of skill. Therefore I hit upon the idea of transforming these skilled artisans into designers. Specifically, I asked the craftsmen to plan a project, draw up the designs, obtain the necessary materials, and arrange for marketing and distribution on their own. I reasoned that if craftsmen could work in a dual capacity as designers, they would be able to become self-sufficient and revitalize the industry in a real sense.

For the first five years we tried several experiments, and I renewed my appreciation of their unerring eye for quality. For example, I asked them to go to the river and find some stones from which wax moulds could be made and cast in metal to create dishes. Even though the craftsmen had no professional training in product design, they were such a good judge of shapes that they turned out beautifully formed vessels with great ease. With their discernment and experience, these craftsmen could create excellent designs without any difficulty.

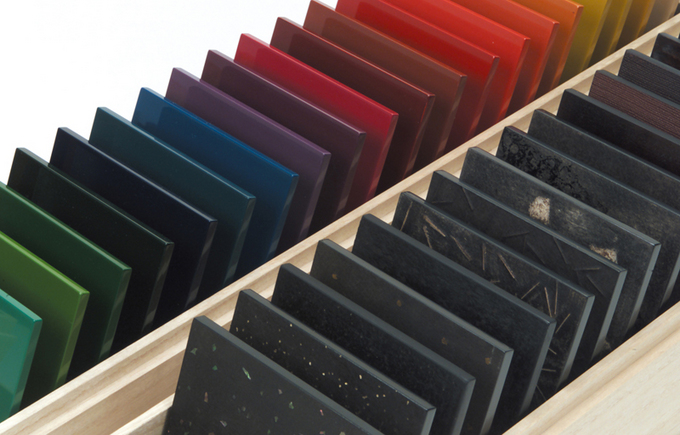

Such experiences were a testament to the high level of the artisans in Takaoka City. Therefore we felt we needed to promote this fact, and created a set of sample plates exhibiting the range of surface treatments which could be done in Takaoka City, ranging from lacquer to metals. We called them "material plates" and they became a useful resource to promote the skills and techniques of Takaoka's local industry.

This promotional tool attracted much attention from many industries with which they had had no previous dealings, such as automobile manufacturers, electric appliance makers, and architectural and interior design companies, both domestic and overseas. This is the gist of my talk in Korea.

KAWAKAMI: Your talk impressed the Korean audience very much and I remember that you were bombarded with questions. In Korea, the chief designer is given much authority and the workload is so full that often it is impossible to confer directly with workers and craftsmen. Of course, the product development process is different from that of Japan, but even so, Mr. Ashitomi's working style of associating closely with the craftsmen, even on minor details, seemed to be a revolutionary approach to the Koreans.

ASHITOMI: As far as I am concerned, what I have done for the local industry project is just the same as what I had been doing when I worked for Sony. I was with Sony from 1985 to 1991, and my boss was very strict and of the opinion that "the designer should always visit the work site." So my colleagues, including those more senior than I, traveled all over Japan, and of course I did so also, especially since I liked to interact with the workers. Sometimes I even paid travel costs out of my own pocket when the company would not permit the expenses.

CAD (Computer-aided design)*1 had not yet been developed, so we drew neat curves by hand with rulers in drawing up the plans for the designs. Based on those hand-drawn plans the craftsman would make a wooden mould, but the actual product would often be slightly different from what we wanted. When this happened I would say, "I'll just make some adjustments", and start to do the work myself. But then the craftsman would stop me: "No, no. That's not the way to do it. Let me do it." Having enjoyed such lively on-site exchanges with artisans throughout my career, I cultivated my relationship with the workers in Takaoka City along the same lines.

YUASA: That is what makes product development in Japan such a wonderful experience. It is the same in Italy. The designer and the artisan work closely together.

ASHITOMI: In those times I often spent the day at the production site conferring with workers and factory workers, returning to the company at night to draw up plans. This grueling schedule was repeated every day, but all the same I enjoyed it so much that I had no intention of letting up. Incidentally, do you know what a jigu *2 is?

KAWAKAMI: It is an adjustment part which improves efficiency in production lines and processing.

ASHITOMI: Machines don't work in the way they are intended when first installed. So we make minor adjustments on-site to correct any quirks the machine is seen to have. Moreover, workers sometimes even invent and construct their own tools to facilitate production. The jigu of each factory or workshop is a display of their ingenuity and initiative, and that is why they are so interesting.

YUASA: I see. I had thought that machines were all made to work exactly alike.

ASHITOMI: The machines only work well after the craftsmen make the necessary adjustments. Sometimes I would comment, "Well, this is an interesting jigu", and the craftsmen would be pleased, replying, "Oh, you've noticed, have you?" By becoming friendly with them through such conversation we get to know each other well, and they turn out work of good quality without my having to check minor details. Sometimes by the end of a project the artisan will have a better eye for the product than me, so that even when I am satisfied he might still find room for improvement, saying, "No, it's not good enough yet."

When this happens I am very pleased because it means that we are in tune with each other. Just handing over plans and drawings will not convey our feelings for the product. Using CAD is even worse. By meeting and talking with them directly, they will be able to understand what we want to convey. The work can proceed smoothly and new ideas will pop out. It is difficult to get to know each other at first, but much better in the long run.

YUASA: There is such depth of mutual trust there. Your comment lets us realize the importance of communication in the working environment. I showed your material plates, the sample plates made by the traditional craftsmen of Takaoka City, to my Italian designer colleagues and they were very impressed. They were amazed by the high level of quality achieved by Japanese artisans.

YUASA: There is such depth of mutual trust there. Your comment lets us realize the importance of communication in the working environment. I showed your material plates, the sample plates made by the traditional craftsmen of Takaoka City, to my Italian designer colleagues and they were very impressed. They were amazed by the high level of quality achieved by Japanese artisans.

You have pioneered the present Japanese movement to reach out to the world through the promotion of the value of our designs. All the same, aesthetics are not the only consideration in product design, since both long-range and short-to-middle-range business strategies must also be taken into account. Recently, however, there seems to be too much emphasis on left-brain strategies, such as design strategy and marketing, and too little time or energy left to focus on good quality or beauty of form.

ASHITOMI: You are right in saying that priority is placed on left-brain strategies. Of course it has its good points, but strategy is not everything.

In the Takaoka project I started by saying, "Let's make this a project with a 1000-year span." Everyone fell out of their seats! Their response was emphatic: "Somebody is going out of business every day. Don't be absurd." But there is something important that can only emerge through a long-range strategy. We talked about proposing ideas covering various time spans, from one year up to a thousand years in the future, after which we would determine whether each idea should be carried out as a long-term or short-term project. This is because in a business, most projects are short term to be carried out the following year.

YUASA: That is the nature of businesses, so it can't be helped. Unfortunately, when market conditions are difficult, it becomes an extremely short-term issue of whether or not the company can weather out the present term.

ASHITOMI: That is why it is necessary to engage not only in craftsmanship, but also in the research and practice of design philosophy and theory. Universities and colleges have previously served this purpose, but now the situation has changed so much. Too much attention is being paid to obtain employment for students and to achieve short-term results, an issue of utmost concern to me at present.

What Are Your Expectations for the Younger Generation?

KAWAKAMI: Although it is true that the youth of today live in a fast-paced world, don't you feel there are also many young people who resist this pace, conscious of the need to take more time in creating quality products? I believe it is partly due to the influence of Mr. Ashitomi's activities that many budding designers today actively visit manufacturing sites and do their own research. I think they hope to make new discoveries through their own initiative.

YUASA: I have received the same impression overseas as well. Recently I often engage in interchanges with young creators in China. While respecting Chinese tradition and customs, they want to modernize and create new styles. Like us, China is changing.

Admittedly there is such pressure to streamline the design process so that it has become more difficult to visit production localities, conduct in-depth research, or fiddle with mock-ups in recent years. A decline in quality as a result of such streamlining is of some concern.

On the other hand, with the growing number of projects in association with young Chinese designers, I notice that they also have a strong interest in preserving their tradition and culture. The approach which is gradually gaining strength is to carry on such tradition and modernizing it to create new designs.

ASHITOMI: Four or five years ago, many of the foreign students in Japan were interested in getting a job at one of the major Japanese companies or at a major corporation in their native country; but now a large number of them come because they are interested in Japanese traditional culture. I like to bait people so I tease them by saying: "China has a longer history, so why don't you go back and study in your own country?" They reply that China is so large that they can study more properly in Japan where culture is more compact.

YUASA: It is nice to hear praise for Japan. And the Japanese should engage in more worldwide activities, for instance, in integrating cutting-edge technology with the traditional arts of Asian countries such as China and Korea. For example, the Hermés company values its craftsmen based on the conviction that the company's worth as a brand depends on their outstanding craftsmanship. Therefore, the company was deeply concerned about how Chinese traditions and craft skills were on the verge of disappearing in the midst of recent economic progress. It was at this time that the CEO of Hermés happened to meet and develop a rapport with a woman who was a Chinese art director. Under the sponsorship of Hermés, a new brand called Shang Xia incorporating the traditional crafts of China and Asia was created in Shanghai in 2010. This brand is one of the directions that design will take in the future, in that it supplies the world with products of high quality craftsmanship in keeping with an Oriental philosophy and lifestyle.

YUASA: It is nice to hear praise for Japan. And the Japanese should engage in more worldwide activities, for instance, in integrating cutting-edge technology with the traditional arts of Asian countries such as China and Korea. For example, the Hermés company values its craftsmen based on the conviction that the company's worth as a brand depends on their outstanding craftsmanship. Therefore, the company was deeply concerned about how Chinese traditions and craft skills were on the verge of disappearing in the midst of recent economic progress. It was at this time that the CEO of Hermés happened to meet and develop a rapport with a woman who was a Chinese art director. Under the sponsorship of Hermés, a new brand called Shang Xia incorporating the traditional crafts of China and Asia was created in Shanghai in 2010. This brand is one of the directions that design will take in the future, in that it supplies the world with products of high quality craftsmanship in keeping with an Oriental philosophy and lifestyle.

ASHITOMI: I hope this goal can be fulfilled in Japan as well, but many Japanese students are still immersed in the designs of Europe and the United States. I suppose that is partly the fault of our generation which was captivated by the West.

YUASA: All of us who were students in the 1980s studied European design, so we do tend to pass this mindset on to the younger generation. Actually, I studied design research, experience design, service design, and universal design at an early stage myself, all of which are necessary concepts for the future.

However, the market for designs and user expectations are both more intense in Asia. This year's Milano Salone, held in April, attracted a larger ratio of customers from Asia, especially China, Korea, and India. I think Japanese designers should also interest themselves more in our neighbors in Asia.

ASHITOMI: Students with such an interest are on the rise, although at a slow pace. A woman who finished graduate school this year comes to mind. She was a practitioner of Iai (the Japanese martial art of swordsmanship), and this must have been one background factor. Her research was based on an idea that there should be some features of traditional Japanese culture, such as tatami mats and ozen trays, which would have a universal appeal to countries all over the world. She was full of vitality and whenever I suggested: "Why don't you go to so-and-so a place? Don't you think it might be interesting?" she would waste no time in going there and talking with artisans and engaging in detailed research. Right now, she is working to fulfill her dream of starting a business with two of her former classmates who are Korean and Taiwanese. Between the three of them, they can cover the four languages of Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and English, which will permit them to do business in Europe and the United States as well as in Asia. I have great expectations for them.

YUASA: That's very promising!

ASHITOMI: They are an especially flamboyant case, but there are many other students who are interested in Japanese tradition, so it is probably a popular theme for this generation. There are many undergraduates as well who have selected Japanese culture as a research subject. On the other hand, probably less than 30 percent of the students have demonstrated an interest in electrical appliances and cars.

ASHITOMI: They are an especially flamboyant case, but there are many other students who are interested in Japanese tradition, so it is probably a popular theme for this generation. There are many undergraduates as well who have selected Japanese culture as a research subject. On the other hand, probably less than 30 percent of the students have demonstrated an interest in electrical appliances and cars.

And there are also a great number of students who are drawn to the life sciences or complex systems science through a fascination with fundamental themes such as the mystery of life and the origin of matter. Today there are very few young students who enter the study of design simply because it is in fashion or because it appears to be a lucrative profession.

Last year, I invited a friend, Hideki Sekine, a professor at Wako University, to give a talk in my class. Professor Sekine researches primitive lifestyles around the world, and is an expert in creating primitive tools and starting fires. He creates musical instruments from natural objects and conducts lectures for children with mental disabilities.

His talks are very popular with the students and I have received requests from the students to invite him again this year. Students can learn much from Professor Sekine. They realize that creating something is not an end in itself, and that much can be accomplished in everyday life through resourcefulness.

KAWAKAMI: Design is based on innovation and ingenuity. There are a growing number of young people who are interested in this aspect of design.

ASHITOMI: That's right. So I am optimistic about the future. Young people today are docile so they do not express their opinions in an aggressive manner, but they are very studious. They know many things that I do not know, and give serious thought to the important question of how people should live their lives.

KAWAKAMI: Recently, a subject that often comes up when speaking with overseas students and colleagues in the field of design is "guiltless production" and "guiltless consumption", that is, the manufacture and consumption of products in a manner which would minimize any negative impact on the environment and society. There are dedicated efforts to design products which can make everybody happy, and much research has been conducted on this topic. Such an issue may strike a chord in the hearts of students and young designers in Japan as well.

KAWAKAMI: Recently, a subject that often comes up when speaking with overseas students and colleagues in the field of design is "guiltless production" and "guiltless consumption", that is, the manufacture and consumption of products in a manner which would minimize any negative impact on the environment and society. There are dedicated efforts to design products which can make everybody happy, and much research has been conducted on this topic. Such an issue may strike a chord in the hearts of students and young designers in Japan as well.

Europe has also changed in the last 10 years. Use of the euro currency in the EU and development of the Internet, which started at about the same period, coincided with changes in their mental outlook. Conversely, closer relationships among countries prompted an interest in the differences in the cultures and traditional crafts of neighboring countries, something which had not been of much concern before. Along with an overall broadening of perspective, there is an increased awareness of the need to delve into the cultural background of each country.

YUASA: Many of my clients are corporations with a worldwide market, and lately the word "global" crops up frequently during meetings. But Europeans shy away when we use this word too often. To them, the word "global" contains the meaning "to homogenize", setting off fears that globalization will rob their country of its individuality.

The fact that the Internet has enabled communication with other people around the world has brought up the issue of national identity, and young people have also been affected by the urgent need to discover more about themselves and their society.

Language and Design

ASHITOMI: Since last year I have stopped "teaching" design in my classes at the university. Instead of lecturing my students, I hold regular meetings with them. Once every week students report on the progress of their design projects and exchange comments freely without regard to seniority or teacher-student relationships. It is in fact a brainstorming session.

ASHITOMI: Since last year I have stopped "teaching" design in my classes at the university. Instead of lecturing my students, I hold regular meetings with them. Once every week students report on the progress of their design projects and exchange comments freely without regard to seniority or teacher-student relationships. It is in fact a brainstorming session.

Everyone gives a presentation and the other students ask questions or give comments or advice. But in the first one or two sessions, almost no one said anything. I had a lot of things to say but I held back. So the first two times, the class ended very quickly without anything happening. But the third time, some students who wanted to lighten the mood of the class began to speak up, giving suggestions for improvement on a project. Then other students also started to comment. On the fourth week, the meeting did not end on time. Creative ideas kept flowing from everyone in the class as well as specific advice on how to proceed. So, one or sometimes even two class hours were taken on each student's presentation. I kept this up for the whole year. When the students graduated they told me: "That was a wonderful class. We'd like to keep on taking it even after we graduate."

YUASA: It is important to verbalize your thoughts through the exchange of opinions. I think that their experience in your class will become an important asset in their lives. In our market studies we often come up against a lack of vocabulary; the Japanese in particular have difficulty putting their feelings into words. When we ask for the opinion of a product to women in their twenties, everyone just says "kawaii" (cute).

ASHITOMI: I agree. As you interact more with people of other countries, there is a need to develop a vocabulary which conveys your feelings. Words have a great influence on design, so much depends on how abundant a vocabulary you can possess. For instance, I can see uniquely Korean elements in a design created by a person who speaks the Korean language.

KAWAKAMI: I suppose the mindset is partly Korean in such a person.

ASHITOMI: When the language is English, an English influence can be seen in the design. Therefore I suppose there is also a design-style characteristic of the Japanese language. I think that discussion of language will become important in creating designs in the future. In Facebook and Twitter, everyone communicates in short, simple sentences. It is not enough just to say "kawaii," but if people can work on their language skills a little more and acquire the ability to express themselves concisely as in waka or haiku poems, that would be stimulating.

KAWAKAMI: Ms. Yuasa, you work with people from many different countries. Do you have anything to comment on the subject of language?

YUASA: Words are very important in design and research. It is not unusual for the same words to convey a completely different meaning or image (in different countries). To put it plainly, there are as many "kakkoii" (good-looking; stylish) as there are regions in the world.

Many times we get excited because we have discovered a new word during on-site interviews in other countries. For example, in India, Japan's image of being "precise and detailed" and "futuristic" is a positive one. When we conduct surveys on designers and other highly educated people we often hear the word "gadgety." The word seems to conjure images such as the instrument panel in the interior of Honda cars and Gundam robot figures.

At first, we were disappointed to hear this word used because it seemed to indicate that Japanese items were gimmicky and toylike, but as we soon realized, it was intended as praise of the highest kind. The word implied that the product was "high in performance and intellectually oriented." We have had many cases similar to this one. But actually, Korean products are more popular than Japanese-made items right now.

(Left) Motorcycles and scooters crowd the streets (Right) Jam-packed? Yet this bus has fewer passengers than usual

(Left) Motorcycles and scooters crowd the streets (Right) Jam-packed? Yet this bus has fewer passengers than usual

(Left) Visit to a middle-class family--Field work is a must (Right) A typical middle-class family in India

(Left) Visit to a middle-class family--Field work is a must (Right) A typical middle-class family in India

KAWAKAMI: What is the appeal of Korean products?

YUASA: It goes without saying that marketing is their strong point. Their design has a straightforward appearance and futuristic style which appeals to middle-class Indians, and their promotional efforts are at the grass-roots level and conducted on a large scale. The major recreations in India are cricket and the movies, and leading cricket players and movie stars have been employed continually in advertisements.

They also visit rural communities and talk with the local people to scout out the needs and expectations concerning the products they represent and also to imprint the company brand name in their minds. Their willingness to do legwork is something we should emulate. Perhaps Indians and Koreans have a similar mindset. They are both practical and sentimental at the same time.

ASHITOMI: I see.

YUASA: Moreover, Korean corporations are sponsors of many top universities in India. They conduct industry-university collaboration programs. Naturally, there is a strong feeling of loyalty to the company by students. After they graduate they become good consumers and patrons of the company. It is a clever long-term strategy.

KAWAKAMI: The Korea of today is full of energy and inquisitiveness. I traveled to Seoul for the preparation of this exhibit and to present a lecture, and I felt the vibrancy of the city. Their energetic music industry is well known in Japan, but the same can be said for the graphic and product design fields. Businesses are also gaining momentum. Those who attended the symposium all had a wide range of interests and many of the questions were specific and to the point.

ASHITOMI: A distinct Korean style is being cultivated. China will probably go through a similar process. They are also enthusiastic about educating designers.

YUASA: Living on the continent, they think in big terms and don't pay as much attention to details as we tend to do. But they are much speedier. We Japanese are often surprised by the speed at which they work. In Japan, the manufacturing process is planned in terms of a production line, so that we draw up plans, give interim reports, and make fine adjustments. We exercise our creativity within this process. We are successful in the quality of the finished product, but it is almost impossible to make major changes midway through the process.

But Korea and China have adopted the European style of authorizing the production manager to make all decisions concerning production; if the manager decided, for instance, that the color should be changed from red to black, then the decision would be passed down as an order without advance notice, and the workers in charge in production would stay up all night making the changes. It is physically grueling and fast-paced, as if participating in a sports meet. If we try to do things the Japanese way, we are soon left behind.

Is yutori (flexibility of spirit) the keyword for Japan?

KAWAKAMI: From these experiences we can see that there is a contrasting situation between Japan and other Asian countries. But at the same time, all of you have great expectations for young designers in Japan. What direction do you think Japan will take in the future?

ASHITOMI: Well, I think the Japanese give themselves leeway in both a good and bad sense. We are a people who take a lot of time to think. For instance, there are numerous traditional lacquer techniques involving bizarre ideas such as mixing in the droppings of a Japanese bush warbler or adding rice to create certain effects. It is difficult to come up with such ideas unless a craftsman has much time on his hands or is very mischievous. The Japanese sensibility is such that they will never miss viewing the cherry blossoms even when they are in dire straits. I feel this kind of yutori is a key concept in Japanese culture both past and present.

ASHITOMI: Well, I think the Japanese give themselves leeway in both a good and bad sense. We are a people who take a lot of time to think. For instance, there are numerous traditional lacquer techniques involving bizarre ideas such as mixing in the droppings of a Japanese bush warbler or adding rice to create certain effects. It is difficult to come up with such ideas unless a craftsman has much time on his hands or is very mischievous. The Japanese sensibility is such that they will never miss viewing the cherry blossoms even when they are in dire straits. I feel this kind of yutori is a key concept in Japanese culture both past and present.

KAWAKAMI: That's very interesting! And this part of the Japanese spirit which does not change, do you think that is a good thing?

ASHITOMI: Yes, I do. That is exactly what I think is uniquely Japanese. It might seem as if we are following in the footsteps of the Europeans, but in certain aspects we have our own unique style of which we are strangely confident.

YUASA: There is a type of creativity which is not swallowed up by speedy development, and there is a type of creativity that enhances the speed at which products are developed. It would be wonderful if these two approaches could be integrated.

ASHITOMI: Yes.

YUASA: The other day I was asked by an Indian designer why the Japanese select their field of study in college simply as a vague extension of their favorite subjects or hobbies. I was surprised at the question, but it seems that in India, they have a clear vision of what profession they will enter and what they want their life to be in the future, so that going to college is a means of fulfilling this vision. In Japan, young people start to look for what they want to do with their life after they enter college. In India, there are many designers in their thirties who have their own businesses, and they are very mature. I feel a difference in the speed at which they are living. Designers in Asian countries are all very mature. They are standing on their own feet.

ASHITOMI: I am an impatient person, so I often tell my students to "work faster", but they rarely do so. But they are active. Former classmates who have entered different professions will get together on weekends at a "secret base" where they study design on their own. There are several such groups and there is also much lateral communication between them. Sometimes I feel that they should join forces and create their own company.

The Future of Design

KAWAKAMI: It is not fair to force the demands of our generation upon young people, so as the last topic of our discussion, can you tell us about your future goals?

YUASA: Certainly. Up until now my work has been passing on the latest European design methods and theories to in-house designers at Japanese corporations, thereby assisting them in creating the products which have enabled them to establish a position of global superiority. But from now on, I would like to make use of my past experience to help fulfill the desires and needs of the users, which have not really been verbalized or expressed. Specifically, this would involve the creation of a scenario based on research on kansei (emotional or aesthetic) related fields. As businesses in Japan and other countries embark on a global strategy I would like to be the spokesperson of the users in each local region, communicating their expectations for design. I would be a translator or communicator of design, so to speak.

YUASA: Certainly. Up until now my work has been passing on the latest European design methods and theories to in-house designers at Japanese corporations, thereby assisting them in creating the products which have enabled them to establish a position of global superiority. But from now on, I would like to make use of my past experience to help fulfill the desires and needs of the users, which have not really been verbalized or expressed. Specifically, this would involve the creation of a scenario based on research on kansei (emotional or aesthetic) related fields. As businesses in Japan and other countries embark on a global strategy I would like to be the spokesperson of the users in each local region, communicating their expectations for design. I would be a translator or communicator of design, so to speak.

KAWAKAMI: That's a very worthwhile goal.

YUASA: An important role of design is to put a shape to ideas, so I intend to make this my personal mission.

ASHITOMI: Recently I have come to feel that "selection" takes priority over "creation." Choice is more important than invention. Even primary school students and kindergartners can create and come up with ideas. However, it is the selection of the idea or design that determines the result.

KAWAKAMI: Selecting a design also means that you must part with the ones you didn't select.

ASHITOMI: That's right. My previous statement can be rephrased to say that it is important to choose what to throw away. If we choose everything that we think is interesting, the result would be chaotic. In the case of the Takaoka project I talked about, we had the craftsmen create many designs on their own and everybody cast votes on which items to market. It was very interesting because although they grumbled that they were not used to creating or designing, they had an eye for good quality and could be relied upon to choose well. So I feel that proper selection will become more important in the future, and I would like to cultivate my ability to discern and make appropriate choices.

KAWAKAMI: Perhaps my approach is similar to both of yours. I have worked as editor of a magazine on design, and came to this job motivated simply by my desire to promote the designs which inspired and amazed me to the public. Now that it has become possible for individuals to disseminate information directly by a wide range of methods, I have begun to think about whether I can express my views on design through other channels.

KAWAKAMI: Perhaps my approach is similar to both of yours. I have worked as editor of a magazine on design, and came to this job motivated simply by my desire to promote the designs which inspired and amazed me to the public. Now that it has become possible for individuals to disseminate information directly by a wide range of methods, I have begun to think about whether I can express my views on design through other channels.

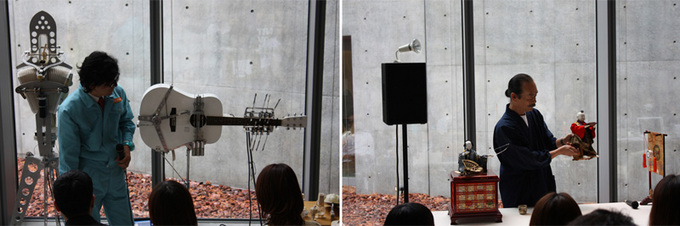

My desire is to arrange opportunities for dynamic discussions and talks. Although design would be the initial topic, I hope to exchange opinions on major issues, such as what we can do for future society, with professionals from many different genres. At 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, where I am an associate director, we are actively engaged in creating opportunities for collaborative projects with people outside of the world of design, such as engineers and scientists. We also extend invitations for such people to participate in our talk shows, and in the exhibit water (2007) directed by Taku Sato, we invited experts such as a researcher of paramecium (an aquatic single-cell organism) and a deep-sea diver. In the bone exhibit (2010) directed by Shunji Yamanaka, a karakuri (automata) master participated in a talk show with the art troupe Maywa Denki. I would like to set the stage for further interchanges between more people, people from different cultures, and people of different generations.

water (2007). The exhibition was a collaborative effort by experts from a wide range of professions, including a cultural anthropologist, design engineer, an authority on the utilization of rainwater, an authority on global hydrologic cycle systems, and a researcher of aquatic life forms. Photo: Masaya Yoshimura/ Nacasa & Partners Inc. Courtesy of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

water (2007). The exhibition was a collaborative effort by experts from a wide range of professions, including a cultural anthropologist, design engineer, an authority on the utilization of rainwater, an authority on global hydrologic cycle systems, and a researcher of aquatic life forms. Photo: Masaya Yoshimura/ Nacasa & Partners Inc. Courtesy of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

bones (2010). Talk event photo: Shunji Yamanaka, Shobei Tamaya (automata master), and Maywa Denki (art troupe) Courtesy of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

bones (2010). Talk event photo: Shunji Yamanaka, Shobei Tamaya (automata master), and Maywa Denki (art troupe) Courtesy of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

ASHITOMI: Each area of specialization has an extremely different vocabulary. I like to talk with medical doctors and scuba divers, but we sometimes find it difficult to understand each other's technical jargon. In such cases, it is reassuring to know that we can depend on Ms. Yuasa and Ms. Kawakami to assist us by acting as interpreters.

KAWAKAMI: How a person views the world differs according to perspectives and specializations, but I hope to pick out elements that are universal and go to the next step up in mutual understanding. Perhaps this movement is in itself a new design in a wide sense. Through our talk I feel we were able to find many ideas that we have in common with each other. Thank you for your time.

Yasuji Ashitomi

President of Saat Design Inc, professor at Tama Art University, and product designer. Ashitomi graduated from Tama Art University in product design in 1985, after which he entered Sony Design Center. He established Saat Design in 1991. Ashitomi is currently engaged in a generalized approach to design which includes product design, development of local industries, and design education.

http://www.saat-design.com

Hoyumi Yuasa

Chief operating officer and design producer of Trinity Co, Ltd. Yuasa began her career in product development and public relations operations at an Italian furniture company. In 1991, she helped start the Domus Design Agency, which was jointly established by Domus Academy (a postgraduate school of design in Milan, Italy), Mitsubishi Corporation, and Uchida Yoko Co., Ltd. She set up her own business in 1997. Her company has undertaken projects in mobile phones, qualitative and quantitative research on automobiles, overseas field research, design trend surveys, and planning of design concepts.

www.trinitydesign.jp

Noriko Kawakami

Journalist. After working as an editor at AXIS (1986-1994) Kawakami became a freelance design journalist. She has also participated in design projects such as the joint Japan-Italy project (1994-1996) of the Domus Design Academy Research Center. Kawakami is also an associate director of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, which is a facility dedicated to a broad exploration of the relationship between people and design. She has authored Realising Design (TOTO Shuppan) and other books, as well as numerous contributions to books about designers in Japan and overseas.

http://www005.upp.so-net.ne.jp/noriko-k/

http://www.2121designsight.jp/en/

*1 A computer-assisted drafting system. It is often used in the fields of product design and architecture because it can draw curved and irregular lines and three-dimensional figures, which are difficult to draw by hand.

*2 A tool which makes it possible to align the position of attachment parts and tools without marking the product with lines or holes in the manufacturing process.

WA: The Spirit of Harmony and Japanese Design Today Exhibition

Tokyo (Japan)

WA: The Spirit of Harmony and Japanese Design Today

Acquainting the world with Japanese products--Paris, Budapest, Essen, Warsaw, Saint-Etienne, Seoul, Tokyo

Exhibition period: June 24 - July 30, 2011. Open on July 18 (holiday) (10:00-17:00)

Venue: Musashino Art University Museum Exhibition Hall 2, 4, 5

Photo:Yuichiro Tanaka

Seoul (Korea)

일본 현대디자인과 조화의 정신

Exhibition period: February 12 - March 19, 2011

Venue: Korea Foundation Culture Center

Saint Etienne (France)

WA: l'harmonie au quotidien - Design japonais d'aujourd'hui

(Saint Etienne World Design Biennale 2010)

Exhibition period: November 20 - December 5, 2010

Venue: La Cité du Design, BIENNALE INTERNATIONALE DESIGN (2010)

Warsaw (Poland)

WA: Harmonia, Japoń ski design dziś

Exhibition period: January 14 - March 28, 2010

Venue: Institute of Industrial Design

Photo:Pawel Wygoda

Essen (Germany)

Wa: The Spirit of Harmony - Japanisches Design heute

Exhibition period: August 20 - September 20, 2009

Venue: red dot design museum

Budapest (Hungary)

Wa: a mindennapok harmóniája - Kortárs japán design

Exhibition period: April 9 - May 31, 2009

Venue: Budapest Museum of Applied Arts

Paris (France)

WA: l'harmonie au quotidien - Design japonais d'aujourd'hui

Exhibition period: October 22, 2008 - January 31, 2009

Venue: Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris

Photo:C.-O.Meylan

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.8.12 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.3.31 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.29 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.11.29 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.13 Crossing Borders, En…