New Encounters at Ware Ware! Korea Japan Film Festival

Tetsuaki Matsue

Film Director

The Japan Foundation hosted the Ware Ware! Korea Japan Film Festival, which was held from March 10 to March 16, 2011 as part of its project "The New Era: Japan-Korea Collaboration for the Future." The festival was divided into four sections: Premiere, Classic, Master (a collection of films directed by Yoichi Sai), and Rookie (a collection of films directed by Tetsuaki Matsue.) A total of 24 films were screened, featuring many Korean-Japan joint productions and starring actors from both countries.

Film Director Tetsuaki Matsue attended the festival as a guest, along with directors Yoichi Sai and Isao Yukisada, and actress/producer Kiki Sugino. Matsue spoke with the audience during question and answer sessions after the screenings and gave us this report on the festival.

Click here for the Korean version: 와레와레! 한일영화축제」는 멋진 만남을 일깨워 주었다

The festival staff showed so much respect for films and directors

I really felt the warmth and kindness of Korea on this trip.

I first visited Korea in 1988, right before the Seoul Olympics, and traveled back and forth between Japan and Korea twelve years ago during the production of Annyong Kimchi (1999). I've been there numerous times since then for TV interviews, film festivals, and sightseeing, but this was the first time I felt so much affection and sympathy. That was most likely due to the Ware Ware! Korea Japan Film Festival, which was featuring a collection of my films, and also because of the huge earthquake that struck Japan while I was in Korea.

You never know what a film festival is going to be like until you actually get there. I have been invited to a number of festivals over the years. At some of these events, the screens were bigger than I expected and there would be a few thousand people in the audience; other times, despite courteous e-mails beforehand, the festival itself was poorly organized and I hated having my films shown to an audience in those conditions.

A first-time festival, especially, is an unknown quantity. This was the first year for the Korea Japan film festival, so, to be honest, I did have my doubts. But my worries vanished with the opening screening. The festival staff showed so much respect for films and directors. The theater had over 100 seats, but it was set up so that the screen was easy to see from every angle. My films cover controversial topics, such as sex, virginity, and pornography, but the programmer still included them in the feature, and gave me an opportunity to talk with the Korean audience. I never thought the day would come when my films would be featured in Korea, but I heard that Lee Kwang-mo, director of Spring in My Hometown (1998), and representative of the BaekDu-DaeGan film center that organized the festival, decided to show a collection of my films, just by looking at my filmography.

Six films I directed over the past decade were screened

When Annyong Kimchi was first shown in Korea, it got a mixed reception - personally, I felt that the reviews were more negative than positive. Even in Japan, an elderly first-generation Korean woman said to me, "Your grandfather must have gone through a lot more. Why didn't you show that in your film?" I responded that the movie was more a record of my family than a film about Koreans living in Japan, but that was not understood at the time. On another occasion, the Korean audience encouraged me, saying, "You are a Korean. Be proud of it!" I wasn't quite sure what to think about that.

When Annyong Kimchi was first shown in Korea, it got a mixed reception - personally, I felt that the reviews were more negative than positive. Even in Japan, an elderly first-generation Korean woman said to me, "Your grandfather must have gone through a lot more. Why didn't you show that in your film?" I responded that the movie was more a record of my family than a film about Koreans living in Japan, but that was not understood at the time. On another occasion, the Korean audience encouraged me, saying, "You are a Korean. Be proud of it!" I wasn't quite sure what to think about that.

Every Japanese Woman Cooks Her Own Curry (2003) is a record of three nights and four days, during which I visited three different women, ate curry, slept over, and in the morning ate the leftover curry which had gotten even better overnight, before moving on to the next woman's place. I was amazed at how different the act of cooking curry was, just because it was performed by a different woman. I enjoyed myself during the shooting, and it became one of my favorite films.

Every Japanese Woman Cooks Her Own Curry (2003) is a record of three nights and four days, during which I visited three different women, ate curry, slept over, and in the morning ate the leftover curry which had gotten even better overnight, before moving on to the next woman's place. I was amazed at how different the act of cooking curry was, just because it was performed by a different woman. I enjoyed myself during the shooting, and it became one of my favorite films.

Seki-lala (2005) was originally produced as an adult video. It is a record of the identities of a third-generation Korean actress, a second-generation Korean actor, a Chinese actress, and myself. We travelled to the hometown of one of the actresses, and visited the house where the actor lived with his father, and filmed them having sex. It is a typical story for a porn film, but pretty exciting when you watch it as a documentary. I wanted to focus on the relaxed mood and conversation that occur in the intervals between sex. It didn't matter if they weren't saying what they really felt. The conversation was definitely something you wouldn't get in a formal interview.

Seki-lala (2005) was originally produced as an adult video. It is a record of the identities of a third-generation Korean actress, a second-generation Korean actor, a Chinese actress, and myself. We travelled to the hometown of one of the actresses, and visited the house where the actor lived with his father, and filmed them having sex. It is a typical story for a porn film, but pretty exciting when you watch it as a documentary. I wanted to focus on the relaxed mood and conversation that occur in the intervals between sex. It didn't matter if they weren't saying what they really felt. The conversation was definitely something you wouldn't get in a formal interview.

In The Virgin Wildsides (2007), I gave video cameras to two guys in their 20s who were still virgins, and asked them to record their everyday life, their thoughts, and scenes where they confessed their feelings to the girls they liked. Although it has not been released on DVD, it is still shown in theaters four years after its premiere. I think that is because the film establishes the problem of virginity as a universal issue that every man must face.

In The Virgin Wildsides (2007), I gave video cameras to two guys in their 20s who were still virgins, and asked them to record their everyday life, their thoughts, and scenes where they confessed their feelings to the girls they liked. Although it has not been released on DVD, it is still shown in theaters four years after its premiere. I think that is because the film establishes the problem of virginity as a universal issue that every man must face.

Annyong Yumika (2009) was inspired by a Korean porn film Junko: the Tokyo Housewife, starring the late Yumika Hayashi, a legendary actress in Japanese adult cinema. I began with the question "why did Yumika appear in this film?" Then, I examined the differences between Korean and Japanese pornography, the life of Yumika, and eventually filmed the last scene of Junko, which would not have gotten made if I hadn't made this movie. I was totally wrapped up in this production for three years.

Annyong Yumika (2009) was inspired by a Korean porn film Junko: the Tokyo Housewife, starring the late Yumika Hayashi, a legendary actress in Japanese adult cinema. I began with the question "why did Yumika appear in this film?" Then, I examined the differences between Korean and Japanese pornography, the life of Yumika, and eventually filmed the last scene of Junko, which would not have gotten made if I hadn't made this movie. I was totally wrapped up in this production for three years.

My latest work Live Tape (2009) is a music documentary shot in one single 74-minute take. It follows musician Kenta Maeno on January 1, 2009 as he wanders the streets of Tokyo's Kichijoji, the neighborhood where I grew up. In 2008, when I lost my father, my grandmother and a friend, I listened constantly to Maeno's songs. It was live music, rather than film, that gave me strength, and yet I still wanted to describe my determination to live in the world of cinema in a cinematic way. With the help of 20 staff and cast members, I was able to bring to life the idea I had at that time of what music and films should be like.

My latest work Live Tape (2009) is a music documentary shot in one single 74-minute take. It follows musician Kenta Maeno on January 1, 2009 as he wanders the streets of Tokyo's Kichijoji, the neighborhood where I grew up. In 2008, when I lost my father, my grandmother and a friend, I listened constantly to Maeno's songs. It was live music, rather than film, that gave me strength, and yet I still wanted to describe my determination to live in the world of cinema in a cinematic way. With the help of 20 staff and cast members, I was able to bring to life the idea I had at that time of what music and films should be like.

The Q&A session after Annyong Yumika was the most exciting

All of my six films were screened in one week at the festival, and we had a question and answer session after every screening. Some of them lasted for two and a half hours, even longer than the film itself, but every session was full of surprises and I really enjoyed being part of it.

After the screening of Annyong Kimchi, I was asked the question I get all the time: Can you eat kimchi now? After the series of sex scenes in Seki-lala, one person said Hanaoka, the porn star featured in the film, was cute; another perceptive questioner noticed things about the music that no one had pointed out before.

Although Every Japanese Woman Cooks Her Own Curry is the most subjective of my works, I left the direction very free, so I was interested to hear one woman say that she liked it the best. The Virgin Wildsides has a scene that always gets a lot of laughs in Japan, but the Korean audience seemed to be at a loss for words and couldn't hide their confusion. I felt a bit sorry for them.

I was really happy when people said that the English and Korean translation of Live Tape was wonderful. Both Maeno and I worked with a translator on the lyrics, and we felt as if we were creating a piece of work from scratch. The translator watched the film carefully before translating it into English. It seemed like our efforts had paid off and I relayed the comments to the translator right away by email.

The liveliest Q&A session was the one after Annyong Yumika. I tried my best to answer the wide range of questions about details that weren't covered in the film, about the Japanese view of pornography, and Yumika's life. When almost two hours had passed, one woman raised her hand and said, "It was very interesting. I would like to thank you on behalf of everyone here." She had waited through the endless questions to say that, which almost made me cry.

Annyong Yumika deals with pornography, a topic generally avoided in Korea. I realized how much of a taboo it was as I encountered repeated problems while interviewing for the film. In Japan, adult cinema and so-called "pink films" (softcore pornography) are considered to be part of the culture, which makes it quite easy to collect materials and data. In Korea, on the other hand, I had great difficulty researching Junko. Before the screening, I actually had to edit some scenes where one of the cast members appears, because acting in porn films is considered an absolute disgrace in Korea.

So I feel a certain anxiety every time Annyong Yumika is shown in Korea. This festival, however, chose the title as its closing film, and the audience thanked me- but really, I was the one who wanted to thank them.

About a week after the earthquake, I recorded the streets of Seoul on video

The success of the sessions owed a lot to the audience and staff, but I personally think the interpreter, Park Min-woo, deserves much of the credit. Drawing on his background in theater, he was able to mimic even my speech habits and timing in his interpretation and helped bring excitement to the audience. The sessions went on for a long time, but he was kind enough to say that he didn't mind because the topic was interesting. I have attended many film festivals at home and abroad over the past 10 years, but have never seen an interpreter as outstanding as Park. It was the first time I'd met an interpreter who added dramatic flair to the job, and kept the audience entertained in that way.

My films tend to have a lot of information. In addition to the conversation between characters, they have captions and sometimes narration at the same time. As a result, it is impossible to convey every piece of information in the limited space available for English subtitles. For that reason, I'd always thought my works were not really suitable for overseas audiences. But I was wrong. With passionate festival staff, an excellent translator, and an audience in search of new experiences, new light could be shed on my works.

Director Tetsuaki Matsue and Interpreter Park Minwoo

The year 2011 marks the 10th year after Annyong Kimchi was released in theaters, and the new encounters I had at the festival in Korea this year meant a lot to me. I am determined to build an audience for my films abroad, but in order to do that I need to change my approach. Times are tough for small movie theaters or "mini-theaters" in both Japan and Korea, and it is difficult to get a showing unless you can promise a good profit. At the same time, I am convinced that independent theaters can overcome these limitations.

When I show my films in Japan, my approach is different from the normal distribution process. For example, in towns where there are no theaters, I use public halls or live music venues. As long as you have a screen, a player, and projector, you can screen a film. This is an unorthodox approach in a movie industry, but people who are eager to see a film don't care where it is shown. I don't turn down offers to show my work, no matter what the conditions, as long as there is an audience, and someone passionate about screening the film. This has worked for me to some extent in Japan. Now, I would like to try the same thing in Korea. Box office value and sales are important too, but new encounters are where it all begins. This is what the festival taught me.

At the Ware Ware! Korea Japan Film Festival, I met people who showed respect for film, were unfailingly polite, and expressed their appreciation, and, as I wrote at the beginning, I really felt Korea's warmth and kindness on this trip. After the earthquake on March 11, I saw many people collecting donations on the streets, and the festival staff showed concern for me when my flight back to Japan was significantly delayed.

About a week after the earthquake, I recorded on video what I saw, felt, and thought while wandering the streets of Seoul. My feelings weren't clear enough to put into words, so I used a song from my iPhone, Maeno's "New Morning" from the album Fuck Me, with the images I had recorded. After returning home, I edited and uploaded the video to the internet. I'm planning to put together my still-inchoate thoughts about Japan, sense of alienation, and my resolutions, and release the work within a year. It will definitely be built on the kindness that I felt in Korea.

Please watch for my next full-length film!

Tetsuaki Matsue

Tetsuaki Matsue

Graduated from Japan Academy of Moving Images. Matsue explored his Korean roots in the autobiographical documentary Annyong Kimchi, which won the prize for best director at the Korea-Japan Youth Film Festival and a New Asian Currents Awards Special Mention at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival. Inspired by adult videos, he shot Seki-lala, a documentary film on Korean porn stars living in Japan. Live Tape, a single-take documentary film starring Kenta Maeno, won the Japanese Eyes Best Picture Award at the 22nd Tokyo International Film Festival in 2009 and the Nippon Digital Award at the 10th Nippon Connection Film Festival (Frankfurt am Main, Germany) in 2010.

The video Matsue recorded in Korea can be seen on the HogaHolic website.

The video Matsue recorded in Korea can be seen on the HogaHolic website.

About the Ware Ware! Korea Japan Film Festival

Dates: March 10 to March 16, 2011

Hosted by: Japan Foundation, Korean Film Art Center BaekDu-DaeGan, Embassy of Japan in Korea

Location: Arthouse Momo in the ECC building of Ewha Women's University

Sponsored by: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Korea-Japan Cultural Exchange Council, Seoul Japan Club

* "Ware ware" is a play on the word for "us" in Japanese, and "Come, come!" (wara wara) in Korean

Arthouse MOMO, the location of the festival

Arthouse MOMO, the location of the festival

Directors Yoichi Sai and Lee Kwang-mo at the opening ceremony

Directors Yoichi Sai and Lee Kwang-mo at the opening ceremony

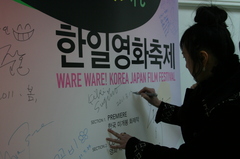

Kiki Sugino signing the banner of the festival. The banner was also signed by Isao Yukisada and Yang Ik-joon, director of Breathless.

Kiki Sugino signing the banner of the festival. The banner was also signed by Isao Yukisada and Yang Ik-joon, director of Breathless.

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…