People-to-People Exchanges and Empowerment in ASEAN <4>

Past, present and future of ASEAN-Japan relations: Centered around people-to-people exchanges

Sato Yuri

Executive Vice President, The Japan Foundation

2024.5.2

【Special Feature 081】

Special Feature: People-to-People Exchanges and Empowerment in ASEAN (for summary on special features, click here)

Dr. Sato Yuri, Executive Vice President of The Japan Foundation, has contributed this article on the theme of this special feature "People-to-People Exchanges and Empowerment in ASEAN-Japan," as someone who has long been involved in Southeast Asia-related research at the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE), particularly study of Indonesia, with a focus on economic, industrial, corporate, and political economy analysis.

Past, present and future of ASEAN-Japan relations: Centered around people-to-people exchanges

Sato Yuri, Executive Vice President, The Japan Foundation

The year 2023 was the 50th anniversary of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation. To commemorate this milestone, many ASEAN-Japan-related events were held throughout the year. In December, the ASEAN-Japan Commemorative Summit was held in Tokyo, at which the "Joint Vision Statement on ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation: Trusted Partners" was adopted. The statement set forth three pillars: 1) Heart-to-heart partners across generations, 2) Partners for co-creation of economy and society of the future, and 3) Partners for peace and stability. An implementation plan was also compiled that sets out actions for the next decade under each of these pillars.*1

Ten years earlier, in 2013, a similar vision statement had been adopted at the ASEAN-Japan Commemorative Summit Meeting on the 40th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation. The 2013 edition of the statement was comprised of four pillars: 1) Partners for peace and stability, 2) Partners for prosperity, 3) Partners for quality of life, and 4) Heart-to-heart partners.*2 By comparison, it can be interpreted that, 10 years later, in 2023, people-to-people exchanges, described as "heart-to-heart partners," has been brought to the forefront of the statement as the foundation of trust between ASEAN and Japan to creatively cope with common economic, social, and security challenges together.

Now that ASEAN-Japan relations have reached this historic half-century milestone, it would be meaningful to take a look back at the relationship to date and consider what kind of future should be shaped together. In this paper, I would like to discuss the past, present, and near future of ASEAN-Japan relations, bearing in mind the perspective of people-to-people exchanges.

1. The beginnings of ASEAN-Japan relations and people-to-people exchanges

Not many people could say for certain what happened in 1973, which is regarded as the starting point of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation. In actual fact, the idea of counting back to 1973 to celebrate milestone anniversaries only became apparent at the time of the 40th anniversary in 2013. In 2003, the first ASEAN-Japan Commemorative Summit was "commemorative" in the sense not that it marked the 30th anniversary of relations, but rather that all ASEAN leaders were meeting together outside of the ASEAN region for the first time. The Summit's outcome document described "the relations of amity and cooperation that Japan and ASEAN had been maintaining over a period of more than 30 years," indicating that the starting point of the relations was not clearly recognized.*3

What was happening between Japan and ASEAN in 1973 was trade friction. The rapid expansion of synthetic rubber exports from Japan posed a serious threat to ASEAN members, which are the world's leading exporters of natural rubber. Malaysian bureaucrats urged ASEAN to take collective action, and at the request of ASEAN an ASEAN-Japan ministerial meeting was held in Tokyo, at which it was decided to establish the ASEAN-Japan forum on synthetic rubber. It is this event that is today regarded as the starting point of the ASEAN-Japan relations. That working-level forum met twice in February and March 1974, and the Japanese side, which at first had been reluctant to engage, agreed to optimize synthetic rubber exports and cooperate in the utilization of natural rubber.*4 In reality, however, from the early 1970s broader economic and social frictions beyond trade had been occurring with various ASEAN countries. The frictions resulted in a boycott of Japanese goods in Thailand in 1972, and the eruption of anti-Japanese riots in Indonesia and Thailand at the visits of Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei in January 1974. Behind these tensions was the perception that the rapid expansion of Japanese exports, investment, and aid was seen as "economic invasion" (an expression by Thai student movement leader Thirayuth Boonmee) in place of "military invasion". The criticism of Japan had spread broadly to Malaysia, Singapore, South Vietnam, and other countries through the Asian Student Congress and the press.*5

This trend of distrust of Japan clearly changed in 1977, the year of a historical epoch: At the second ASEAN Summit held in August 1977 in Malaysia, the leaders of Japan, Australia and New Zealand were invited, and Prime Minister Fukuda Takeo attended the summit, holding the first ASEAN-Japan summit meeting; the ASEAN-Japan Forum was also held in March and November 1977, before and after the summit; and in the Philippines, the last country of Prime Minister Fukuda's Southeast Asian tour, he announced Japan's basic policy on Southeast Asian diplomacy, which would later become known as the "Fukuda Doctrine." The basic policy has three key principles: First, Japan, a nation committed to peace, rejects the role of a military power and is resolved to contribute to the peace and prosperity of Southeast Asia, and of the world community; second, Japan will do its best for consolidating the relationship of mutual confidence and trust based on "heart-to-heart" understanding; third, Japan will be an equal partner of ASEAN and its member countries, and cooperate positively with them in their own efforts to strengthen their solidarity and resilience.*6 President Ferdinand Marcos, who waved off Prime Minister Fukuda on his return flight to Japan, stated that the prime minister's assurances about Japan's role in Southeast Asia dispelled all concerns about Japan's vision for the region.*7 On the ASEAN side, it had just set up a system that could serve as a diplomatic entity in 1976, by holding its leaders' summit for the first time in the ninth year since its establishment and opening its secretariat in Jakarta. On the Japanese side, as friction not only with the United States but also with Southeast Asia grew more serious, the 1974 Central Education Council Report "On International Exchanges in Education, Science, and Culture,"*8 for example, clearly stated that "Japan must deeply reflect on the fact that its international exchange activities to date have too often focused on political and economic exchanges," and it was based on this recognition that "the expansion of people-to-people exchanges" emerged as a core issue.

This was how people-to-people exchanges emerged as a critically important diplomatic theme, as a means to correct external distrust and friction arising from economic success of post-war Japan. The central stage was Southeast Asia, where ASEAN began to develop its diplomacy and Japan coined its key "heart-to-heart" phrase. People-to-people exchanges as the realization of such heart-to-heart relations thereafter grew to become a variety of programs, including "The Friendship Program for the 21st Century" proposed by the Nakasone administration in 1983 through which approximately 4,000 young people from ASEAN were invited to Japan, the "ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Exchange Program" proposed by the Takeshita administration in 1987, the "Peace, Friendship, and Exchange Initiative" of the Murayama administration in 1994, and the Japan-East Asia Network of Exchange for Students and Youths (JENESYS) that began in 2007.

2. The Japan Foundation's ASEAN projects

Throughout the history of people-to-people exchanges between Japan and ASEAN, The Japan Foundation (JF) has continued to play a distinct role as Japan's only public organization specializing in international cultural exchange. The establishment of JF in 1972 itself is closely related to the situation in Southeast Asia described above. The regional subcommittee of the preparatory committee for the JF (chaired by Nakayama Ichiro) noted that "projects that prioritize the United States and Southeast Asia should be proactively considered."*9 In actual fact, very soon after its inception, in 1974 the first JF offices in Asia were established in Bangkok and Jakarta.

The concept that underpins all of JF's ASEAN programs is to engage in two-way exchanges on an equal footing. The Japan Foundation Law of 1972, the legal basis for the establishment of the organization, was accompanied by the following supplemental resolution. "Particular attention should be paid to the fact that, as the basic stance of the Government of Japan on international cultural exchange, it is similarly of the utmost importance not only to deepen understanding of other countries about Japan, but also to deepen the understanding of our people about other countries."*10 It is recognized that this two-way reciprocal aspiration enshrined in the supplementary resolution was realized as the Japan Foundation ASEAN Culture Center, which was established within JF in 1990 in response to the above-mentioned "ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Exchange Program".*11 Even prior to 1990, JF had introduced Southeast Asian culture to Japan through various programs, including the Asian Traditional Performing Arts (ATPA) exchanges (1976-88), and the South Asian Film Festival (1982), which was the first initiative to introduce Southeast Asian films to Japan. The ASEAN Culture Center (1990-1995) provided a platform to enlarge and ensure the continuity of such two-way exchanges. Then the ASEAN Culture Center developed into the Asia Center (1995-2003) under the government's "Peace, Friendship, and Exchange Initiative", and its aim took a step forward from two-way cultural introductions to "dialogue," "collaboration," and "cooperation" between people. For example, "Lear," a two-year new production based on Shakespeare by theater artists from six countries including Japan, became a milestone in international co-productions, being performed in Japan, ASEAN countries, Europe and Australia. The Asia Leadership Fellow Program (ALFP) that was jointly organized by JF and the International House of Japan (I-House) invited mid-career leaders from ASEAN and other Asian countries to reside in Japan for two to three months, during which they discussed common challenges and made field visits with Japanese experts. Many participants of ALFP went on to become influential leaders in their own countries. The program also helped to form a trans-national human network across the region.*12

JF's renewed focus on ASEAN region began in 2014. At the ASEAN-Japan Summit in 2013 to commemorate the 40th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation, it was announced that JF would implement the "WA Project: Toward Interactive Asia through Fusion and Harmony," and the Asia Center of JF was reinstated in 2014 for this purpose. As Prime Minister Abe Shinzo had returned to power at the end of 2012 and selected Southeast Asia for his first overseas visit, his administration's emphasis on ASEAN gave impetus to the WA Project. Ten years later, in 2023, at the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Commemorative Summit, it was announced that JF would continue its work for the next decade under the "Partnership to Co-Create a Future with the Next Generation: WA Project 2.0." For this project, JF works on ASEAN-Japan exchange programs, not in a special department called the Asia Center, but across JF's three pillars, namely arts and culture, Japanese-language education, and Japanese studies and global partnership, in other words, as JF as a whole. While the philosophy of JF's ASEAN programs has consistently been to expand and deepen two-way exchanges, the emphasis has evolved to "collaboration" since 2014, and now to "co-creation."

JF's ASEAN programs from 2014 to the present and into the future consist of two main areas. One is cultural and people-to-people exchanges, and the other is the NIHONGO Partners. Cultural and people-to-people exchanges encompasses a broad range of contents. A type of activities in which members from ASEAN countries and Japan mix to work together covers such areas as sports, music, dance, performing arts, documentary films, and so on. For example, a football exchange program named ASIAN ELEVEN brought together more than 600 coaches, players, and league officials from ASEAN countries, Timor Leste, and Japan, and then the first official Southeast Asian selection team was formed, with Japan hosting an U-18 match in Fukushima and Thailand hosting an U-16 match. It proved to be highly popular in ASEAN, where there are many football lovers.*13

The "ASIAN ELEVEN" team, comprised of boys under 18 selected from 11 countries in Southeast Asia

There are also activities that address issues common to ASEAN and Japan, where members from each country gather to think and learn mutually. One example is the HANDs! (Hope and Dreams) Project for disaster prevention. Southeast Asia and Japan are regions that are susceptible to natural disasters, including earthquakes, tsunami, typhoons and volcanic eruptions. Through this project, approximately 100 people from the participating countries visited disaster-affected areas in ASEAN countries and Japan, and continued training activities with the aim of becoming young leaders in disaster prevention education. Next, they took the lead in developing disaster prevention activities in their countries, including evacuation drills at elementary and junior high schools, ultimately spreading learning opportunities to 90,000 people throughout the entire program.*14

In contrast, even in cases where there is no shared commonality within the region, this makes opportunities for mutual learning even more meaningful. For example, in terms of religion, specifically Islam, there is a great deal of difference within the ASEAN region, with the countries of Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei having majority Muslim societies, whereas Muslims are a minority in countries like the Philippines, Thailand and Cambodia. Islam is also not a particularly familiar presence in Japan. In the TAMU (Talk with Muslims) Project, Muslim youth from ASEAN countries came to Japan to talk with university students across the country. In so doing, the program provided an opportunity for Japanese participants to deepen understanding about Islam and also for Southeast Asian Muslims to gain many mutual insights.*15

Collaborative disaster education project "KIDSUP" led by young leaders in the "HANDs! Project" (in Indonesia)

The second of JF's programs is NIHONGO Partners, where ordinary Japanese people from university students through to post-retirement seniors spend about 10 months in an ASEAN country, in principle assigned to one local secondary school, and work as an assistant for local Japanese-language teachers, partnering with the students. In the 10 years since 2014, more than 3,000 people have participated in this program.*16 Although this program is not two-way in terms of the flows of people, its impact is certainly bidirectional. The local communities welcome a NIHONGO Partner, a precious native Japanese speaker. The NIHONGO Partner experiences life as the only Japanese in the local community. He or she gets into the local community, tells people about Japan, while at the same time, learns from them, and is helped by those around him or her. Many participants in this program report that after returning to Japan, their view of their own local multicultural society has changed.

A NIHONGO Partner who work as a partner of a local Japanese-language teacher and students in a secondary school.

The JF's WA Project generated more than seven million people exchanges between Japan and ASEAN countries, including cultural and people-to-people exchanges and NIHONGO Partners programs, in the ten years from 2014 to 2023, despite the period of over two years when the flow of people was interrupted by the COVID pandemic. The Partnership to Co-create a Future with the Next Generation that has just begun in 2024 aims to create exchanges more than 10 million people in the next ten years.

3. Message from ASEAN to Japan

In order to provide hints as to how we shape the future of ASEAN-Japan relations, I would like to share the messages of panelists from ASEAN countries at an international symposium organized by JF in March 2023. The symposium was titled, "International Symposium on the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation--Entering a New Stage toward a Global Partnership, next generation scholars discuss future prospects of ASEAN and Japan relations." One or two mid-career or young panelists from each ASEAN country and Japan took to the stage to engage in free discussions covering three areas; politics and security, economy and society, and cultural and people-to-people exchange.*17

ASEAN Indo-Pacific Outlook (AOIP) was a topic of discussion as panelists discussed their own perceptions of ASEAN's role in the region. The AOIP, which was adopted at the ASEAN Summit in 2019, is a vision to expand the space of peace, stability, and prosperity that ASEAN has nurtured to the Indo-Pacific region. At a time when major powers are jostling for supremacy, and major power-led visions for the Indo-Pacific region are emerging, the panelists had the following to say about the AOIP. The AOIP proposed by ASEAN ultimately represents an inclusive vision and inherent in it is a desire to find a means of breaking away from the containment concept espoused by major powers. The countries of ASEAN do not seek to take a values-based approach. AOIP is primarily concerned with economic development for all members of the region rather than security. AOIP can therefore likely transcend its focus on the Indo-Pacific region to become a global public good.

The panelists at one of the sessions, all born in the 1980s and currently in their 30s, appraised ASEAN-Japan relations from their own experiences, and shared the following candid view of Japan. The image of Japan in Southeast Asia may be stuck in the 1980s. It is therefore important to reintroduce the "Japan of today." It is perhaps time to reposition the image of Japan in the context of the long history of relations with Southeast Asia. We, the younger generation, are interested in taking ethical actions. In order to get to know more about the realities of modern Southeast Asia, we hope that Japanese people will make more visits to the region. Japan seems to be disinclined to actively explain and promote itself.

"International Symposium on the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation--Entering a New Stage toward a Global Partnership, next generation scholars discuss future prospects of ASEAN and Japan relations"

A panelist described the 50-year relationship between Japan and ASEAN as having created a "safe space" and went on to call for expanding that space to a wider region. Another panelist noted as follows: The past 50 years of ASEAN-Japan history have been marked by the building of trust and now we have a surplus of trust; but this surplus is not something that you can just deposit somewhere and the interest will increase.

Listening to the views of young and mid-career experts from ASEAN countries, we are reminded that we must never rest on our laurels, taking a hard look at the progress that has been achieved in ASEAN-Japan relations to date, which succeeded in transforming distrust into trust over the course of 50 years. The societies of Southeast Asia are all making rapid and dynamic progress. However, in Japan we are left to ponder the reality of being told that "the image of Japan is stuck in the 1980s," notwithstanding the popularity of anime and Japanese cuisine. Given how Japan still tends to see Southeast Asia as a region that require assistance, the 30s generation of the region may indeed see the Japanese mindset as being "outdated." Without efforts the current trust surplus will not increase, but rather will diminish as the days go by.

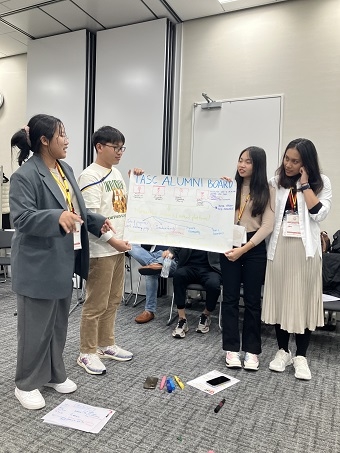

We Japanese must first get a better picture of the realities of ASEAN today. We must be able to appreciate their confidence when they talk about the AOIP. To pass the trust surplus on to future generations without letting it diminish, Japanese people need to update their perception of ASEAN. The keywords that will underpin people-to-people exchanges in ASEAN-Japan relations in the coming decade are "next-generation" and "co-creation." A forerunner for such actions was the ASEAN-Japan Youth Forum "Take Actions for Social Change (TASC)" organized jointly by JF, the Kamenori Foundation and the ASEAN University Network (AUN) in 2023.*18 A total of 30 university students from ASEAN countries and Japan, all around 20 years of age, split into three teams to consider social common challenges, namely "environment and disaster education," "diversity," and "aging society." The students spent four months engaging in field study and training relating to each topic, finally gathering in Japan to publicly present the solutions they had devised. Furthermore, all the participants spent time together looking back on and sharing their four-month experiences among the different teams, putting into their own words how the program had changed them, and declaring their own next steps towards the future in front of fellow members. The mixing of more young Japanese into this circle of bright smiling faces sharing and exchanging "profound and life-changing experiences" (words used by a participant) will undoubtedly be the most important foundation for ASEAN-Japan relations in the near future, and for Japan in Asia more broadly.

Final day of the TASC program, in which members are presenting their next steps in the future

- *1 English version of the Joint Statement on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website: https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100597190.pdf. This document was based on the report compiled by the Expert Panel for the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation established by the Government of Japan. In that report, the three pillars were set out in the reverse order to the statement, (3) (2) (1).

- *2 ASEAN Secretariat website.

https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/2013/resources/40thASEAN-Japan/finalvision%20statement.pdf - *3 Ministry of Foreign Affairs website.

https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/asean/year2003/summit/evaluation.html https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/kaidan/s_koi/asean_03/pdfs/tokyo_dec.pdf (in Japanese)

Oba Mie (2023) "Nichi-ASEAN 50 shuunen: Nihon ha Tounan Ajia to dou mukiatte kita no ka" ["Japan-ASEAN 50th Anniversary Year: How has Japan approached Southeast Asia?"], Kokusai Mondai (International Affairs), No. 713:53-64. - *4 Md Nasrudin Md Akhir (2023) "From Conflict to Cooperation: How the Synthetic Rubber was Instrumental in Culminating ASEAN-Japan Ties," The International Journal of East Asian Studies 12(2):23-40. doi.org/10.22452/IJEAS.vol12no2.3

- *5 See IDE (various years), Yearbook of Asian Affairs (in Japanese); chapter on Thailand in the 1973 edition, and chapters on Thailand and Indonesia in the 1974 edition.

https://ir.ide.go.jp/search?page=1&size=20&sort=custom_sort&search_type=2&q=4115 - *6 For an original English text of Fukuda's speech, see "The World and Japan" Database, https://worldjpn.net/documents/texts/docs/19770818.S1E.html. As literature about the Fukuda Doctrine specifically focusing on its "heart-to-heart" aspects, see Ihara Nobuhiro (2019) "Fukuda Takeo no Tounanajia seisaku ni okeru 'kokoro-to-kokoro no fureai'" ["'Heart-to-heart interactions' in Fukuda Takeo's Southeast Asia policy"], Global Governance, 5:83-97. doi.org/10.51054/sgg.2019.5_83

- *7 See IDE, Yearbook of Asian Affairs (in Japanese); 1978 edition concerning the situation in the Philippines, p. 342.

- *8 Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology website.

https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chuuou/toushin/740501.htm (in Japanese) - *9 The Japan Foundation (1990), Kokusai kouryuukikin 15 nen no ayumi [The 15-Year History of the Japan Foundation], p. 26.

- *10 Ibid., p.21.

- *11 Study Group on the Japan Foundation as a Special Corporation, "Proceedings of the Study Group on the Japan Foundation as a Special Corporation from 1972 to 2003," (Vol. 2), p. 42.

- *12 The Japan Foundation (2006), Kokusai kouryuukikin 30 nen no ayumi [The 30-Year History of the Japan Foundation], p. 249.

- *13 The Japan Foundation website.

https://asiawa.jpf.go.jp/culture/projects/asia_football/ - *14 Ibid. https://asiawa.jpf.go.jp/culture/projects/hands/

- *15 Ibid. https://asiawa.jpf.go.jp/culture/projects/exchange-with-southeast-asian-muslim-youth/

- *16 Ibid. https://asiawa.jpf.go.jp/partners/

- *17 Ibid. https://www.jpf.go.jp/j/project/intel/exchange/asean/symposium/2022/03-01.html

- *18 Ibid. https://www.jpf.go.jp/j/project/intel/exchange/youth-forum/2023/03-01.html /GiFT website. https://j-gift.org/37435/

Sato Yuri

Executive Vice President (EVP) of The Japan Foundation (JF). Upon graduating from the Faculty of Foreign Studies of Sophia University she joined the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE), engaging in Southeast Asia-related research, particularly about Indonesia, with a focus on economic, industrial, corporate, and political economy analysis. She served as an overseas research fellow in Indonesia (1985-88, 1996-99), as a special advisor for the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KADIN; 2008-10), and as executive vice president of IDE and the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO; 2015-2019), before assuming her current position in October 2021. As EVP of JETRO she was responsible for economic exchanges with Southeast Asia and Oceania, and as EVP of JF has engaged in initiatives to promote global partnership and Japan studies overseas. She served as president of the Japan Association for Asian Studies (JAAS), and currently serves as representative of the Colloquium on Indonesian Studies in Japan (Kapal), director of the Japan Indonesia Association Inc. (Japinda), and a lecturer at the University of Tokyo. She received her doctorate in economics from the University of Indonesia. She has authored and edited many papers and publications relating to Indonesia and Southeast Asia, and her work Keizai Taikoku Indonesia [Economic Giant Indonesia] won the 24th Grand Prix Asia Pacific Award and the 16th Okita Memorial Prize for International Development Research.

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…