Crossing Borders, Engaging in Exchanges and Harnessing the Power of Creation amid COVID-19

Interview and Contribution Series <5>

Sakoda Kumiko, Deputy Executive Director of Hiroshima University

March 10, 2021

[Special Feature 073]

In this fifth issue of our special feature "Crossing Borders, Engaging in Exchanges and Harnessing the Power of Creation amid COVID-19" (click here for a special feature overview), we welcome Sakoda Kumiko, Deputy Executive Director of Hiroshima University and Specially Appointed Professor of Morito Institute of Global Higher Education. She specializes in Japanese-language education and Japanese-language teaching methods and engages in Japanese-language education in Japan and overseas. We asked her to contribute her views on the current situation in the field of Japanese-language education. What challenges have emerged according to a survey of Japanese-language teachers in 17 countries and regions around the world? How are teachers coping with Japanese-language education amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

Pros (Okage) and Cons (Sei) of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Field of Japanese-Language Education

Sakoda Kumiko

Learning in the Gateway to Japan at the Centre for Foundation Studies in Science at the University of Malaya in Malaysia, where the Japan Foundation dispatches Japanese-language specialists

Learning in the Gateway to Japan at the Centre for Foundation Studies in Science at the University of Malaya in Malaysia, where the Japan Foundation dispatches Japanese-language specialistsAs people often say, "I didn't realize the importance of health until I became sick." there are many things that we do not realize until we lose them. We do not realize that our way of life may not last forever until we have encountered an incident that dramatically changes the situation we took for granted, such as our parents or the setting in our hometown.

In January 2020, a viral pneumonia of unknown cause was reported in the news in Wuhan, China, and the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) quickly spread around the world. Then, life as we knew it was no longer the same.

The same applied to the field of Japanese-language education. In-person classes were replaced by online learning at many universities in April. Although some universities have resumed in-person classes, most classes are still held remotely at many universities. I really miss these face-to-face classes.

Because I received a request for writing an article on how the field of Japanese-language education has changed amid the COVID-19 pandemic, I decided to send an email to 31 Japanese-language teachers, who are my friends, in 17 countries and regions around the world, including four in Japan, 12 in Asia, eight in Europe and Africa and seven in Oceania and North America, and asked for a field report. I then analyzed the pandemic's pros (okage) and cons (sei). Pros are used for good news, as in "the crops have grown well thanks to the rain," while cons are used for bad news, as in "a game was cancelled because of the rain." In this article, I will try to search for pros and cons caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

I asked the following five questions:

(1) Has your teaching style changed due to the pandemic?

(2) What are advantages and disadvantages of online classes?

(3) Is there educational inequality?

(4) Have you noticed any changes in students' motivation?

(5) What remains unchanged even after your teaching style has changed?

Among the 17 countries and regions from which I received replies, only Taiwan was able to maintain regular classes without making the shift to online lessons. In other countries and regions, almost all classes have been held online since spring 2020, and both students and teachers were deeply distressed. As of October 2020, educational institutions in some countries and regions, including France and New Zealand, are returning to in-person classes. In many countries, however, they are conducting either on-demand classes (teachers prepare e-learning content that students study whenever they want) or livestreamed classes (both teachers and students gather at the same time for class using the Internet), or hybrid classes which use both.

Advantages cited by Japanese-language teachers include:

●Saving time without commuting

●Being able to view materials as many times as desired, wherever students want

●Improving IT skills

Conversely, a great many disadvantageous examples were sent from teachers along with their grievances. Major examples include:

●Communication between students and the teacher and among students has become difficult compared with in-person classes.

●It is hard to see whether students are in fact viewing and understanding classes.

●Teaching and evaluating conversation, pronunciation and writing are difficult in a class with 30 or more students.

●Due to spotty online connections, students' concentration and learning efficiency decrease proportionately with repeated interruptions.

●It takes a lot of time for the teacher to prepare for an on-demand class and a hybrid class.

The list goes on and on.

In livestreamed classes, students' faces cannot be shown because of the unstable Internet connection. In such cases, the teacher is forced to give lessons to the list of student names displayed on a dark computer screen and feels isolated, without ever knowing if the students are really there, listening and understanding the lesson. One of the teachers said that some students participated in the class using a mobile phone while enjoying shopping or eating at a restaurant. There were also cases where students attended the lesson only at the beginning and the end. Teachers work out strategies to contend with such cases. They check the students' attendance by frequently asking them questions, checking their level of understanding by giving them assignments and trying to support students by communicating with them outside of class.

With regard to educational inequality, some universities have lent computers and tablets to students, provided subsidies and taken proactive measures. However, in many cases students are unable to take lessons on a stable basis due to problems with their Internet connection and household circumstances such as limited space or the presence of siblings.

Many responses attributed students' declining motivation to an inability to meet their classmates and a difficulty to maintain their concentration and a stable Internet connection. However, there were some pros, as seen in the active participation of students who were too shy to ask or answer questions due to fears about the reactions of classmates in an in-person class setting. Some also reported that tech-savvy students had no problem completing assignments and even kept on studying on their own.

On the other hand, students with low IT skills eventually faded out or lost interest in joining the classes in some cases. However, the responses suggest that teachers are making personal efforts by writing comments on students' homework and staying connected with them via instant messaging and by setting up office hours. Nevertheless, educational inequality and maintaining motivation do not concern only students; some responses showed cases in which teachers with low IT skills experienced setbacks because they were unable to master them even after receiving training and leaving their jobs. These reports break my heart.

My analysis so far may give the impression that there are more cons than pros from the COVID-19 pandemic, but Japanese-language teachers demonstrated their ingenuity and came up with ideas to turn around the situation. There were positive comments in reports such as: "I was able to master IT skills for online classes," "I would like to think about education that will cultivate self-learning skills of students by utilizing IT," "We can apply IT skills for online classes to the education of children with disabilities," "I will learn video creation skills from popular YouTubers" and "I want to work with IT specialists and develop AI that can be used for language learning." Reading these comments, I felt guilty of blaming everything on the COVID-19 pandemic because I was desperately hoping to resume in-person classes based on my belief that the foundation of education is direct communication with students.

Seminar for Japanese-language teachers subsidized by the Japan Foundation (El Salvador, 2019)

Seminar for Japanese-language teachers subsidized by the Japan Foundation (El Salvador, 2019)The last question asked, "What remains unchanged even after your teaching style has changed?" There were many diverse responses, which made me realize that this question asked about the educational philosophy of individual teachers. I nodded in agreement with some replies and felt impressed by other perspectives. Although the replies were sent by e-mail, they were powerful and inspirational, with the voice and face of each respondent filling the screen as if we were video-chatting.

Because I cannot present all of the responses, I have taken the liberty of summarizing what these Japanese-language teachers value even after their teaching style has changed.

(1) Connecting with students through communication and feedback

(2) Learner-centered and learner-based education

(3) International and cross-cultural understanding

With regard to (1) Connecting with students through communication and feedback, there were opinions such as: "It is important not only for the teacher and students but also for students among themselves to learn from each other and teach each other through communication" and "Students associate with others and learn how to interact with others through classes, so it is important to respect diversity by working with people from different backgrounds." As for (2) "Learner-centered and learner-based education," there were many opinions such as: "The central player in education and classes is students" and "Autonomous learning will become more important, and the teacher will play the role of a facilitator." Regarding (3) International and cross-cultural understanding, I received the opinion, "The pandemic made me more aware of the importance of not only imparting knowledge but also of teaching international and cross-cultural understanding."

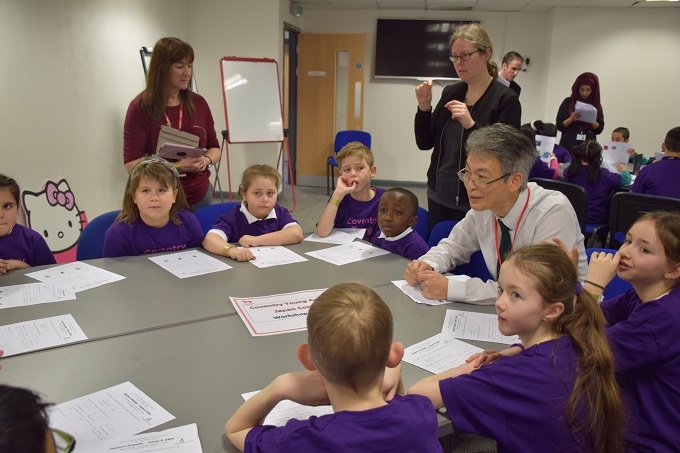

An "Experience Japan" event for elementary school children conducted by Japanese-language specialists from the Japan Foundation, with the aim of introducing Japanese-language education in primary education in the UK (2017)

An "Experience Japan" event for elementary school children conducted by Japanese-language specialists from the Japan Foundation, with the aim of introducing Japanese-language education in primary education in the UK (2017)I always thought the day would come when the use of ICT would be essential for the future of Japanese-language education, but the sudden and rapid spread of online classes have brought major changes in the awareness of both students and teachers who were caught unprepared. The forced shift in teaching style reminded me how strongly our daily in-person classes were based on the connection between students and teachers. While online classes are efficient and rational, there is a disadvantage in being unable to see, understand and connect with the students even if their faces are on screen. This, I feel, has an immense impact.

According to reports from teachers in the field, motivation is said to have declined for many students. It is not the fault of online classes per se. I think it was caused by the forced change in teaching methods without fully understanding the advantages and disadvantages of holding classes online. Students' motivation will rise even in online classes if a teacher with advanced ICT skills can take advantage of the technology for hybrid classes.

Even if the times have changed and the teaching style has changed, the teachers' spirit of wanting to build a relationship of trust with students through classes and cherish each learner will remain unchanged. The pandemic has created new challenges on how to establish connections and build a relationship of trust with students on the other side of the screen.

I had to agonize over what to write for this article for a while. On the other hand, thanks to this article I was able to feel encouraged and inspired by the attitudes of my friends who make their utmost efforts in Japanese-language education in different countries and regions while dealing with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. New challenges in online classes have also become evident. It is my fervent hope that we have the power to transform the current challenges from the pandemic (cons) into positive future results (pros).

Breakdown of respondents to the survey by country and region is as follows.

[Asia] 16 respondents

●4 from Japan

●2 from Taiwan

●2 from South Korea

●4 from China

●1 from Thailand

●2 from Indonesia

●1 from Hong Kong

[Europe and Africa] 8 respondents

●1 from France

●3 from Germany

●1 from Italy

●1 from Spain

●1 from Hungary

●1 from Egypt

[North America & Oceania] 7 respondents

●1 from Canada

●2 from U.S.A.

●2 from Australia

●2 from New Zealand

Contributed in November 2020

Related Articles

Back Issues

- 2025.7.31 HERALBONY's Bold Mis…

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…