Japanese and Me

January 2019

Marei Mentlein

(German-Japanese translator, TV producer)

There's no single label that covers everything Marei Mentlein does. She employs her Japanese language skills in a variety of fields, appearing in German language programs produced by NHK TV, reviewing mystery novels and movies for the German Embassy in Japan's German lifestyle guide, and providing German-Japanese interpreting and translation for TV news programs. "I'm a German for a living," she explains. Ms. Mentlein tells us about her introduction to the Japanese language, her experience learning Japanese, and the career she's built using her language skills.

At the entrance to ZDF German Television's Tokyo bureau, where Ms. Mentlein serves as a producer.

It all started with "羊"

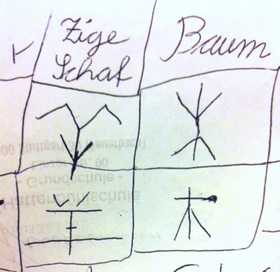

My first encounter with the Japanese language was when my aunt took me to a folk museum in Germany. I was about six years old. I'd fallen in love with Asian cultures from the pictures I'd seen in children's books, so my aunt took me to the Asia corner of the museum. As I looked at the exhibits, spellbound by the gorgeous kimonos and samurai swords, a hanging scroll caught my eye. On it was written "羊", and next to that was a caption along the lines of "This Chinese character (kanji) means 'sheep.'" I was fascinated: not only did the character look like a sheep, it was sleek and refined, using only a few lines. This culture of communicating using characters based on pictures, rather than letters, really appealed to me.

The characters "羊" (sheep) and "木" (tree), copied from the folk museum Ms. Mentlein visited as a child.

You can learn a lot from variety shows!

I developed a strong interest in Japan, and at the age of 15, I started studying Japanese in earnest. What I really liked at first was the existence of hiragana and katakana. They're so convenient - once you memorize them, you can start writing words in Japanese and using verbs! But there are so many of them, so I decided to make a kana memory game I could play by myself. I'd write a hiragana on one card, and on another card I'd write its equivalent in Roman letters. Then I'd try to find all the hiragana-letter pairs.

When I was 16, I traveled to Japan for a 10-month study abroad program. For about a year, I attended a public high school in Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture. Although I'd studied Japanese in Germany, it wasn't enough to get by. Back then, online and electronic dictionaries weren't yet widely available. So I had to listen to others speak and observe my surroundings. In the process, I discovered that as long as I had a rough idea of the topic, I could actually pick up a lot of what was being said from the atmosphere and the few words I could understand.

One thing that really helped my Japanese studies was TV. Especially variety shows. They use everyday Japanese, so (leaving grammatical correctness aside) I could learn how to speak naturally. It's a convenient way to pick up trendy Japanese words like ikumen (men who take an active role in child rearing), sabasaba-kei joshi (straightforward girls), JK (joshi kosei or female high school students), owacon (outdated), riaju (riaru ga jūjitsu - a person who leads a fulfilling life), and so on.

And, unlike German TV shows, Japanese shows of all kinds use captions to deliver information. When a variety show wants to highlight what one of the performers said for extra effect, they'll show part of it onscreen as a caption. This is actually great for learning! For example, when you've heard a word before but don't know the kanji characters for it, all you have to do is watch the captions and you'll learn them naturally.

Incidentally, another good trick is to turn on Japanese subtitles when you watch Japanese movies and TV shows on DVD. A lot of times the subtitles get shortened due to lack of space, though, so personally I recommend TV.

The words and characters Ms. Mentlein learns by watching TV help her in her translation work.

The challenge of leaving things unsaid

Sometimes, even if there are words to express something in Japanese, people leave them unspoken. It's what you'd call "reading between the lines." Japanese people send signals to the person they're talking to--"You understand without me saying, right?!"--and expect the other person to read between the lines to get their intent. German people generally like a clear "ja" (Yes) or "nein" (No). Using the Japanese equivalents "hai" and "iie" in the same sense as you would in German can make the other person feel uncomfortable. Japanese "iie" is about 100 times blunter than German "nein." If someone asked you, "Do you like sushi?", instead of "iie," you'd use a negative verb, like "I don't really like it" or "I don't eat it." Come to think of it, I haven't used "iie" in several years.

The difference between Japanese and German is clear in business negotiating style as well. In Japanese, it's standard etiquette to decline offers in a soft, gentle manner. Even when rejecting a proposal, you'd never say, "That's unacceptable!" You'd say, "We'll take that into consideration" or "That may be difficult."

When I'm speaking Japanese, I try to switch my brain to Japanese mode as much as possible rather than starting with German and trying to translate.

All the work I'm doing, I owe to the people I know

My first job in Japan was appearing on NHK's TV program for learning German, which I had to audition for. It was a job I could do even without much Japanese, but when rumors started spreading that there was a German who could read and write Japanese, soon enough I was asked to help out with translation. It was my first time doing translation. Since then I was often asked to do translation and interpreting. Because there are few people who know both German and Japanese, I've actually never had to look for work. There is a Japanese-German translation and intepreting industry, but all the experienced professionals are swamped with work, and when they can't take on a job, they ask other people they know. So there's no sense of hostile competition between us; everyone gets along really well.

As a German in Japan, when I do translation and interpreting, it's mostly from German into Japanese. But it's hard to produce elegant Japanese on the level of a native. That really used to bother me. Then again, there are nuances only a native German speaker can understand, so I've turned that into one of my strengths.

In the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake, I happened to meet a correspondent from a German TV station, who confided, "Our Tokyo bureau has reporters who only speak German and English and reporters who only speak Japanese and English. It's a problem because we have to translate Japanese interviews into English and then into German, and nuances inevitably get lost." I decided to be bold and said, "I can help with that!" And that's how I came to work in the bureau.

(L) Interpreting for an Austrian mystery novelist Andreas Gruber (center). Working as an interpreter lets Ms. Mentlein meet people and hear stories she wouldn't otherwise have a chance to.

(R) These days, Ms. Mentlein often appears on radio and TV to talk about Germany.

Some things, you can only do if you're not perfect

Japanese is a fascinating and profound language. I could study it my whole life and never get tired of it. Even with all the rapid advances in artificial intelligence and automated translation software, there are things you can't translate well unless you understand culture, customs, and human feelings. I'm sure there are still lots of chances for all you Japanese language learners out there to find success! You don't have to speak Japanese like a native. Just use it in your own unique ways and make the most of your diverse backgrounds, and fun things are bound to come your way!

Twitter (available in Japanese): https://twitter.com/marei_de_pon

Young Germany (mystery novel & film reviews, available in Japanese):

http://young-germany.jp/category/mareimystery/

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…