Interviews of Renowned Architects: Documentary Film shown at 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale

Norihito Nakatani (Architectural historian and Professor, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Waseda University)

Tomomi Ishiyama (Film director)

The Commissioner and the project members of the Japan Pavilion

In November 2014, when the curtains was about to fall to resounding applause for the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, the documentary film, Inside Architecture - A Challenge to Japanese Society, was shown and a talk session were held for in Tokyo. The film, directed by Tomomi Ishiyama and shown in a space on the stilted ground floor of the Japan Pavilion, had been produced exclusively for the Biennale.

At the Venice Architecture Biennale 2014, the national pavilions were curated under one theme of "Absorbing Modernity: 1914 - 2014" by the curator of the Biennale, Rem Koolhaas. Led by Commissioner and curator of architecture Kayoko Ota, the Japan Pavilion featured an exhibition in the style of a museum for architectural resources centered around the 1970s, in line with the theme "In the Real World: A Storehouse of Contemporary Architecture." While this "storehouse" of architecture made its appearance on the second floor of the Japan Pavilion, the movie directed by Tomomi Ishiyama was screened on the stilted ground floor during the exhibition period, at a somewhat more open space that faced the passers-by. This film is a bold venture comprising an 18-hour long interview shooting of many people from the field of architecture, including seven renowned architects such as Arata Isozaki and Charles Jencks. What were the intentions behind producing this full-length documentary that spans more than 50 minutes. We talked to the director of the Japan Pavilion Project Team as well as the producer of this film, Norihito Nakatani, and film director Tomomi Ishiyama, about production anecdotes and other aspects of this documentary film.

(From the special screening of the film and talk session at the JFIC Hall "Sakura," on the second floor of the Japan Foundation, on November 19, 2014)

The film, Inside Architecture - A Challenge to Japanese Society, discussed in this article, will be re-edited and screened in cinemas at the beginning of summer 2015.

The "storehouse" packed with all types of architectural resources from the 1970s and beyond

Nakatani: I am greatly honored to have the opportunity to present this film in Japan, as I had wished to show a part of what we had done at the exhibition in the faraway land of Venice, to the people of Japan.

We conceived of the Japan Pavilion as a "storehouse" that contained archives of architectural resources from the 1970s and beyond, and the exhibition was set up based on the concept that visitors would be able to enter the "storehouse" as it was. Many visitors stayed for nearly one hour and viewed the exhibits carefully, and I believe that the impact of the exhibits themselves made the exhibition an enjoyable experience for visitors ranging from children to researchers alike.

The overarching theme proposed by Rem Koolhaas was "Absorbing Modernity," which aimed to present the architectural aspects of various countries throughout the century-long span from 1914 to 2014. The Japan Pavilion focused particularly on the period of modern Japanese architecture from the 1970s and beyond, when the characteristics of contemporary Japanese architecture of today first emerged. At the same time, a 100-year exhibition that lends objectivity to the main exhibition was also held. For example, blueprints of the original architectural drawings of 50 renowned modern Japanese architectural works were bound and displayed for visitors to browse freely. Since it was not possible to bring the original drawings to the exhibition site, we considered the possibility of bringing blueprints instead. We found and purchased a blueprint machine that was about to be disposed of, and even did some printing at the venue itself. As blueprints provided a good sense of the actual drawings, the exhibit was well received. Visitors browsed through the blueprints carefully, and took pictures as well.

I think that the wealth of architecture media can be brought up as one of the factors contributing to the richness of Japanese architecture today. At the exhibition venue, we also provided displays of in-house newsletters and mimeographed zines from leading magazines, including those that have ceased publication, as well as unpublished drafts by the British architectural critic Chris Fawcett who had been active in Japan but had died early. These artifacts, which embodied the thick layers of Japan's architecture media, were also available to the visitors for free browsing. In addition, the TAU magazine published by SHOTENKENCHIKU-SHA Publishing, which was discontinued after the release of just four issues in 1972, was fully displayed across an entire wall surface. This expressed the rich fertility of a media that could pack such an extent of layout in a single magazine. Even visitors who could not understand the language were impressed by the editorial and layout of the magazine.

We also brought a small number of original items to the exhibition. Amongst these was a chair made by Atelier Zo used by town councilors at Shinsyukan, which is the community center in Miyashiro, Saitama Prefecture. This chair was designed based on the same conceptual method as for architecture, and encompassed elements of architectural design. This was transported in its original form from Shinsyukan to the exhibition site and put on display. Many visitors sat in it at the exhibition, just as if it were a tribal chief's chair.

Today, I have introduced mostly the parts of the exhibition outside of the main exhibition, but there was a huge variety of exhibits.

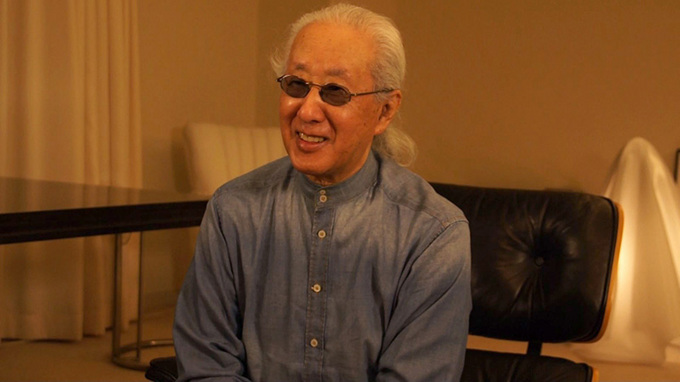

Arata Isozaki

©Tomomi ISHIYAMA

The film as a record of the moment when we realized that architecture was changing the world

Nakatani: While Japanese architecture is highly appraised around the world today, the film documents how this high appraisal had come about, by whom it was fostered, and how it had spread from the 1970s to the time of the bubble economy and, further, to the present day. At the same time, it traces the international context of how phenomena that was unique to Japan had been modified and placed in the context of other countries in the world. The film featured mainly Arata Isozaki, as well as Toshio Nakamura, Toyo Ito, Tadao Ando, Peter Eisenman, Charles Jencks, and Rem Koolhaas.

Left: Charles Jencks, Right: Peter Eisenman

©Tomomi ISHIYAMA

Rem Koolhaas

©Tomomi ISHIYAMA

Ishiyama: I was invited to direct this film at the stage when Nakatani-san had already made the decision to record and preserve the words of these people, and had selected the people he wanted to interview in the planning process for this film. As expected, Nakatani-san spoke to the architects in his position as a historian, so the interview continued in a calm way. I had to make that into a film. There was quite a bit of conflict during the production process, and Nakatani-san and I had many exchanges on our views. Rather than wishing to film a video of myself as a historian "asking" questions to star architects, I wanted to stand witness at a site where human beings were clashing with one another. That is why I drove Nakatani-san by saying, "I want you to fight properly. I want you to ask questions that even would incur anger." However, this was not an easy task. To be honest, at the stage when we were conducting the interviews, I did not have any sense of core in myself about making the film that felt like "this is it," and we finished the entire filming itinerary without having gained any sense of assurance on my part. Nevertheless, when I make a film, I believe that the editing process matters more than anything else. Even if the filming did not proceed on-site as intended, I think that the most important point in making this movie lay in my ability to draw out my own intentions through the editing process.

My greatest consideration when editing this film was who everyone's words had actually been directed at. Although all the characters had been interviewed individually at separate locations, I felt that it would be perfect if I could stage it such that they all appeared to be in discussion and making claims to one another in the film, as if they were playing catch-ball with words. I like productions with a good sense of tempo, so I took the bold step of not leaving much room for trailing emotions in any of the scenes. As a result, the film conveyed a busy atmosphere. While some viewers may feel that it is shifting to the next scene before they have really understood the first scene, I hope that they will watch the film over and over again if they have the chance to do so. I watched the interview clips several hundred times during the editing phase, and I found that when I listened to the interviews after gaining knowledge about the wonders of the architectural structures these people had built, as well as the historical significance of their work, each and every word gradually began to take on much greater weight. It is a film that shows people from older age groups speaking energetically, and I would definitely like young people to also watch this film.

Nakatani: I showed this same film to my students at Waseda University today. After watching it, they were open-mouthed and looked blank. Students today have had no actual experience of the bubble economy. Of course, they also know nothing about the 1970s. It is not possible to make them understand how architecture has the power to accelerate a society, and to grasp a situation in which one could witness, with one's own eyes, that acceleration. I am a little troubled by this. What has become of our quarrels and hard work? Ishiyama-san and I were discussing this as we came here (laughs).

Ishiyama: I feel that the students would falter even with respect to the subject of postmodernism. It is very difficult for them to accept it as something that is their own. However, this film does not simply feature star architects talking in a world of a different dimension that is distanced from our own transient world. Rather, hints have been hidden everywhere in the film to help us perceive these ideas as individual and personal problems. For instance, in the film, Toyo Ito makes the following comment about creating architectural works in modern society: "There are some things that must be done through manipulation." Is this true? Can we not do it without manipulation? These are things that we have to consider for ourselves going forward. Everyone is free to take their own perspectives, but I hope in particular that the younger generation adopts a personal perspective toward these ideas, in the same way as I have just explained.

Nakatani: In the future, I think that the question of how we can convey Japanese modern architecture from the 1970s to the present day will become an extremely important issue. With respect to the exhibition contents that we have produced, I would like to direct an honest question to the many of our predecessors who are here today, and who have knowledge about that era. In the period from the 1970s to the economic bubble, and then further to the burst of the bubble, I think we had an impression that reality was being moved along by architecture. I believe this was particularly true for architectural works that were produced by Arata Isozaki. However, looking at the reactions of the students, I felt that they were wondering, "Does architecture move the world?" Did they respond immediately and with sympathy to such thoughts? No, they did not. Rather, there were people who experienced a sense of reality in episodes such as the trial and error that we went through for the exhibition contents, and in that sense, how is the architectural world of today positioned? I felt that there was a marked contrast.

Ishiyama: Previously, I had also shown this film to some architects at the university. I was told that it made them feel very depressed. I would like us all to consider if it is truly so. The 1970s, when Toyo Ito and Tadao Ando launched their careers, had been a very difficult time with the oil shock, economic recession, and the rise of general construction contractors. This was a time when there were hardly any projects for architects who worked from ateliers, and I think that they had to work really hard to produce their works. To me, these are stories that bring great hope--how did they confront society and develop to become the great architects who are still active today? If we were to consider the film from this perspective, I am sure it would not seem like a depressing film.

The prominent uniqueness of Arata Isozaki when we think about architecture in the 1970s

Nakatani: To me, this is a film about Arata Isozaki. A certain architecture magazine did a feature on the Venice Biennale, and in the discussion held for that feature, it was pointed out that, "You are focusing on the period after the 1970s. If so, why Arata Isozaki isn't here?" However, there was this film. Rather, I should say that I had felt that the presence of Isozaki was entirely different from all the other people, to the extent that if we did not seal it into the film and ensure that it did not become muddled with other things, the concept of this exhibition would have crumbled. In this sense, my interpretation is that we made good use of a two-layer structure in the Japan Pavilion, comprising the "storehouse" and the stilted floor.

The first title that we had come up with for the film had been "The Commissioners." Here, "commissioners" refers to the network, as well as the specific people, who had been movers and shakers of the architectural world in a global context, particularly from the 1970s to the 1990s. Ultimately, the title and the overall emphasis of the interviews were changed under Ishiyama's hands. This is a part of the job of a director, and I did not have any opinions about it at all.

Ishiyama: I had liked the title "The Commissioners" very much. However, while talking to the Japan Pavilion Commissioner Ota-san, and to Nakatani-san about who the actual commissioners were referring to, I felt that it was focusing too much on Arata Isozaki. Since this was not my original intention for the film, I had not wanted to make a film where Arata Isozaki had been the only lead character, even if Nakatani-san had captured this film in that way and many viewers had also probably felt the same way when they watched the film. The responses and reactions of those who had watched this film were very diverse; there were people for whom Jencks left a strong impression, and those for whom Toyo Ito had left an impression. Hence, I personally feel that I have produced a film that can be perceived in virtually any way.

Nakatani: For example, it is true that Jencks had a very attractive personality even though this was the first time I had met him. We could also describe Toyo Ito, and of course, Rem Koolhaas and Peter Eisenman as commissioners, but I think that Arata Isozaki is still in a league of his own. One of these signs is the fact that the other architects often talked about themselves in distancing themselves from Isozaki. Another sign is that commissioners typically have a clear purpose for the project, and make use of various forms of media to educate the general public on their purpose. However, in the case of Arata Isozaki, the destinations of his plans were very deep, and would suddenly no longer be visible to me at times. I listened very carefully with regard to this aspect. That scene is one that Director Ishiyama described as one with "trailing emotions" and therefore did not turn up in the final film. However, I think that the director had been discerning to keep it out of the film. I think it had been well worth it to ask Tomomi Ishiyama to direct this film.

Today, Ishiyama-san asked me if I had a "father complex" toward Arata Isozaki (laughs). For my generation, particularly, it would be possible to develop a "father complex" toward Arata Isozaki. Having admitted that, and having had Ishiyama-san provide a re-interpretation from a different position from mine, I think that there is a strong possibility that we could have produced a film that comes with many different facets of meaning.

(Editor: Ayako Tomokawa)

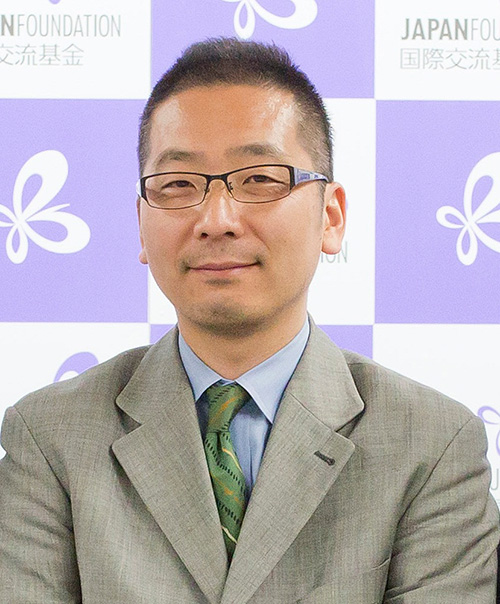

Norihito Nakatani

Norihito Nakatani

Architectural historian and Professor, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Waseda University. Nakatani began with research on writings on carpentry of the early modern era, and continued with research on the continuity of land characteristics and its impact on the present day (theory of pre-existing characteristics), and led a project that documented changes by revisiting the civilian homes that Wajiro Kon had visited. Most recently, he has also been conducting research on villages that have existed for a thousand years. His publications include Kon Wajiro "Nihon no Minka" Saiho (Revisit of "Private House in Japan" Wajiro Kon visited; as a member of the Rekiseikai Group, Heibonsha, 2012), Seberarunesu + Jibutsu Rensa to Toshi, Kenchiku, Ningen (Severalness + Chain of Things and City, Architecture, and Human; Kajima Institute Publishing, 2011), and Kokugaku, Meiji, Kenchikuka (National Learning, Meiji and Architects; Ikki Publishing, 1993). In 2013, Nakatani received the Kon Wajiro Award presented by the Japan Society of Lifology (as a member of the Rekiseikai Group), and the Writer's Award presented by the Architectural Institute of Japan.

![]()

Tomomi Ishiyama

Tomomi Ishiyama

Film director, born in Tokyo. Ishiyama is a graduate of the Department of Housing and Architecture, Faculty of Human Sciences and Design, Japan Women's University. She is a recipient of the Fulbright Scholarship, and completed her Master's studies in Urban Design at the City University of New York. While studying in the United States, she developed an interest in film-making, and began to train under Director Isao Okishima upon her return to Japan. She appeared in Okoru Saigyo (A2009) directed by Okishima. Her first full-length movie, Last Days of Summer, was presented in the Japanese Eyes category of the 25th Tokyo International Film Festival, and became a hit.

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…