Falling for the Charms of Contemporary Cambodian Architecture

Hiroshi Matsukuma (Professor, Kyoto Institute of Technology)

Corresponding with the traveling exhibition "Parallel Nippon--Contemporary Japanese Architecture 1996-2006" held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, from January to February 2014, the Japan Foundation requested Hiroshi Matsukuma, an expert of contemporary Japanese architectural history, to conduct a lecture for the general public, students of architecture, and professionals in Phnom Penh. He also held a dialogue with the renowned Cambodian architect, Vann Molyvann, who names French master Le Corbusier as one of his influences. In this article, Professor Matsukuma reflects on the experience of conducting the lecture and on seeing Cambodian architecture in person

My Message in Cambodia

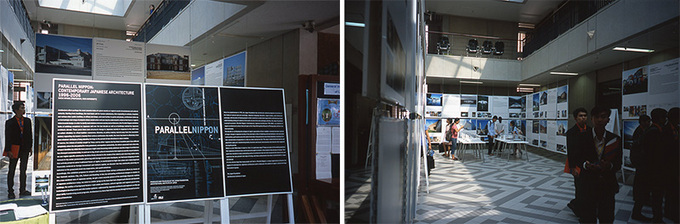

For four days from February 18 to 21, 2014, I visited the capital of Cambodia, Phnom Penh for the first time at the request of the Japan Foundation. My mission there was to give two lectures to Cambodian architects and students of architecture and civil engineering, corresponding with the "Parallel Nippon--Contemporary Japanese Architecture 1996-2006" exhibition that was being held at the Cambodia-Japan Cooperation Center (CJCC) . The objectives were to increase understanding and awareness of the culture of Japanese architecture, and to promote the exchange of specialized information through these lectures.

This exhibition had originally been planned by the Japan Foundation and the Architectural Institute of Japan as an exhibition that would travel across the globe for about 10 years. After being held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography in 2006, the exhibition travelled to various parts of the world, reaching Cambodia as well. The exhibition featured contemporary Japanese architecture in the 10-year period after Japan's economic bubble burst, and included a wide range of architectural creations from small houses to art museums, libraries, theaters, schools, stations, and airports, as well as buildings constructed overseas. The total number of structures introduced at the exhibition exceeded 100. Opening up the exhibition catalog, which was handed out to visitors beforehand, one might have assumed that the structures were built a long time ago, when in fact it was only eight years ago. Perhaps this impression reflected the reality faced by Japan, of having experienced a national crisis in the form of the Great East Japan Earthquake on 11 March 2011, as well as deepening confusion throughout the country. This might explain why the pictures of gorgeous contemporary architecture that decorated the pages of the catalog seemed strange.

With such doubts in my mind, I honestly felt very bewildered when considering what I could say in the lecture as an expert of contemporary architectural history. Nevertheless, although I had received the request in January right before departing to Cambodia in February, I had in fact long wanted to visit the country for the opportunity to meet Vann Molyvann (1926- ), a major architect leading the post-war contemporary architecture in Cambodia. Furthermore, I had also heard about his respect for the celebrated Japanese architect Kenzo Tange (1913-2005). By chance, 2013 was the 100th year of Tange's birth, and a large retrospective exhibition was held in the Kagawa Museum in Takamatsu City, where his representative work, the Kagawa City Hall (1958) was built. I was one of the minor members on the executive committee for this exhibition. This, I felt, was a sign of destiny

Based on the small amount of information about Molyvann that I could obtain, I decided the contents of my lectures. I would talk about attempts in outstanding contemporary Japanese architecture to harmonize Western concepts with Japanese climate, culture, and traditions, and introduce specific examples of these efforts aiming to present the message that in the modern era, in which the whole world is gradually experiencing the effects of globalization, it is only by maintaining deep roots in locality that we are able to create a better environment and gain universality of architecture with creativity. I introduced three Japanese architects: Kunio Maekawa (1905-1986), Junzo Sakakura (1901-1969), Takamasa Yoshizaka (1917-1980) who had studied under Le Corbusier (1887-1965), the French master architect and leader in contemporary architecture in the 20th century, in addition to Kenzo Tange. I also talked about the work and architectural concepts of the two contemporary architects whose works were on display in the "Parallel Nippon" exhibition - Yoshio Taniguchi (1937- ) and Hiroshi Naito (1950- ). Would I be able to communicate my intentions to the architects and students of Cambodia, and to Molyvann? On February 18, I travelled from Kyoto in the middle of winter, to tropical Cambodia with anxiety. I arrived at Phnom Penh International Airport in the evening of the same day, and headed for the hotel in the taxi that had been sent for me. The residents of Phnom Penh, a large city with a population of 1.5 million people, had finished their work for the day and were returning home. The roads were filled with cars, motorbikes, and the three-wheeled "tuk tuk." The streets were alive with energy. Even though this was my first visit, what came into my field of vision seemed somehow nostalgic.

Preserving Cambodian Traditions through Architecture

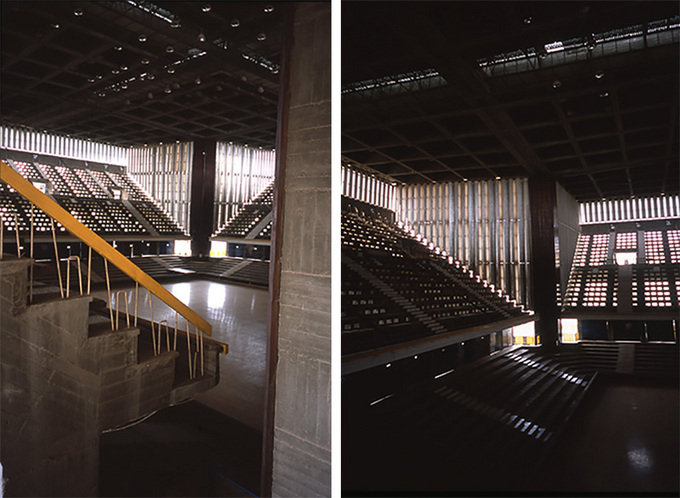

On the morning of February 19, the day after I arrived, I was immediately taken around Phnom Penh city to see the architecture, guided by my interpreter, Navi, who had previously studied at the National Institute of Technology, Tokuyama College. The first place where we headed was the Olympic Stadium (1964), one of the representative works of Molyvann. I was overwhelmed by the powerful concrete structure that was designed to withstand the harsh climate of Cambodia, with its heavy rains and strong sunshine. The spectator seats and walls in the stadium, which were not equipped with air-conditioning, were designed specially to increase ambient light exposure and air circulation. The interior of the stadium was filled with light, exuding the atmosphere of a magnificent church. The spacious landscape of the athletics grounds adjoining the stadium also left a deep impression on me.

Olympic Stadium

Exterior of the Olympic Stadium

Exterior of the Olympic Stadium

Interior of the Olympics Stadium

Interior of the Olympics Stadium

(Left) Main stands of the athletics grounds, (right) Olympic cauldron and spectator stands in the athletics grounds

(Left) Main stands of the athletics grounds, (right) Olympic cauldron and spectator stands in the athletics grounds

Next, we toured the Independence Monument (1958) and the Chaktomuk Conference Hall (1961). Both of these buildings were designed in solid forms that had inherited the traditions of Cambodia, with motifs based on the stone culture used on structures such as Angkor Wat, as well as the traditional wooden building structures that had existed during the Khmer dynasty. We also stopped by the Central Market (1937). This was not designed by Molyvann, but was built during the French colonial period. It is the largest market in the city, and many residents continue to visit this art décor building today. With assistance from France, this market was renovated in 2010. The interior space, with its dome made from reinforced concrete, is filled with a divine light. Various products were laid out under this light, ranging from daily necessities, electronic appliances, food products, used clothing, and souvenirs, to precious stones, creating quite a spectacle. We also visited the National Museum and the Royal Palace, giving me the chance to come into contact with another aspect of Khmer culture.

In the evening, to my surprise and some bewilderment, a meeting had been planned for myself and a high-ranking government official in charge of architectural affairs. I spoke to him about the wonders of the contemporary architecture that I had seen so far, as well as my hopes that Cambodia's world-class cultural heritage would be well-preserved, and introduced DOCOMOMO, a global organization that propounds the preservation of contemporary architecture. The official informed me about the current situation whereby a building standards law had not yet been enacted despite the dramatic economic growth that the country was experiencing in recent years. I also received an abrupt request for recommendations and support toward the architects' society that had finally been established. Although I was taken aback by this unexpected conversation, I felt once again the weight of the expectations placed on the world of Japanese architecture.

(Left) Independence Monument, (right) Chaktomuk Conference Hall

(Left) Exterior of Central Market, (right) Interior of Central Market

(Left) National Museum, (right) Royal Palace

Vann Molyvann's Profound Thoughts on Architecture

On February 20, the next day, after I delivered the lecture I had prepared on contemporary Japanese architecture to students of Cambodian Mekong University in the morning, I visited Molyvann's residence (1966) in the afternoon. In the reception room, I gave to Molyvann a catalog of Kunio Maekawa's 100-year anniversary exhibition held in 2005, and talked with him for about an hour. From his talk, I learned that Molyvann had close relations with Maekawa and Tange, as well as architectural historian Hiroyuki Suzuki (1945-2014). He had also visited the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan (1961) designed by Maekawa during his visit to Japan, and had been impressed with it.

Vann Molyvann was born in 1926, and went to study in France in 1946. Although he first studied law at the Sorbonne (University of Paris), he switched to study architecture instead. From 1947 to 1956, he studied architecture at Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts). In 1956, after returning to Cambodia and having been strongly influenced by Le Corbusier, he was appointed State Architect at the young age of 30, under the patronage of King Sihanouk. He designed many of the state facilities in Cambodia, which had recently gained independence from France in 1953. Molyvann served as the Rector of the Royal University of Fine Arts in 1965 and the Minister for National Education and Fine Arts in 1967. However, during the Pol Pot regime which was begun with the military coup led by Marshal Lon Nol in 1970 and cast a shadow on Cambodia's modern history, Molyvann was forced to seek refuge in Switzerland. Thereafter, in the long period of his exile from Cambodia lasting 20 years from 1971 to 1991, he put much effort into the preservation and repair of Angkor Wat. Despite the short time I had on this trip, I was able to obtain a glimpse, for the first time, into his calm and frank personality, noble will, and profound thoughts on architecture. If there had been no political conflict in the 1970s I was certain that he would have designed many more buildings as the State Architect of Cambodia, rivaling even the creations of Alvar Aalto from Finland (1898-1976). Nevertheless, from 2009 to 2012, with cooperation from students of the local Royal University of Fine Arts, as well as Yale University in the United States and Moscow State Technical University in Russia, William Graves led efforts to recover the drawings that had been lost during Molyvann's exile from Cambodia through the Vann Molyvann Project, a non-profit undertaking that seeks to preserve the entire body of Molyvann's work for future generations. A collection of his works is scheduled to be published next year by a publishing arm of Princeton University. Molyvann's home, where I heard the details about his life, was also a wonderful space that was in harmony with Cambodia's climate, culture, and traditions.

(Left) Exterior of Molyvann's residence, (right) Molyvann and the author

After the meeting had ended and we had left his residence, I visited 100 blocks of low-cost detached housing groups (1965) built in the suburbs of Phnom Penh, guided by a young local architect who had also participated in the Vann Molyvann Project. Here, Molyvann employed a method that is believed to have been influenced by Le Corbusier's "Minimum House" concept, and attempted to create a unique structure inspired by traditional wooden residential houses that had existed during the Khmer period. The housing groups were structures with wooden roofs placed over frames with high floors, supported by fine concrete pillars, creating a settlement that exuded an atmosphere that was both new and nostalgic at the same time.

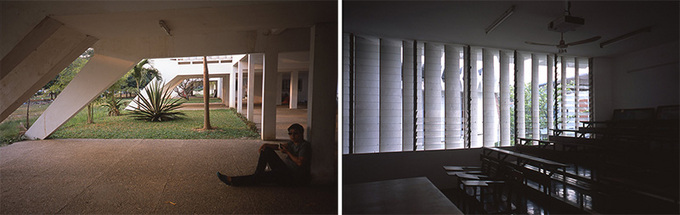

After that, we visited school buildings of the Institute of Technology of Cambodia that were designed by a Soviet design team led by a female architect (name not known). I was greeted by a scene that wove together a permeable structure that was filled with light and naturally ventilated, and students talking and laughing. I felt as if I had found the origins of architecture that contemporary Japanese architecture has lost--that of creating spaces that provide people with peace of mind.

Detached housing groups

Institute of Technology of Cambodia

Exterior of the Institute of Technology of Cambodia

(Left) Corridor on the first floor of the Institute, (right) Corridor on the second floor of the Institute

(Left) Exterior of the Institute, (right) Corridor of the Institute

Next, on February 21, the last day of my visit, I delivered once again my lecture on contemporary Japanese architecture to Molyvann, students and faculty of the Institute of Technology of Cambodia at CJCC where the "Parallel Nippon" exhibition as well as the Japan-Cambodia Kizuna Festival were being held. While it may have been somewhat presumptuous on my part, at the end of my lecture I told the students, "In an era of increasing globalization, it is more important than anything else to connect globally universal methods with locality. I hope that you never forget that Cambodia has a wonderful architect, Mr. Molyvann, who is a pioneer in achieving this." In response, Molyvann, who was sitting in the first row, rose and gave words of encouragement and inspiration to the students. The sight of the students looking at him with great respect and applauding loudly left a deep impression on me. After the lecture ended, I visited the Institute of Foreign Languages (1972) and the Main Hall of the Royal University of Phnom Penh (1968), both of which were designed by Molyvann. These were also vibrant architectural structures that seemed to embrace the students.

Venue of the "Parallel Nippon" exhibition

Institute of Foreign Languages

(Left) Exterior of Institute of Foreign Languages, (right) Exterior of classroom block of the Institute of Foreign Languages

(Left) Piloti space of classroom block of the Institute, (right) Interior of a classroom in the classroom block

(Left) Main Hall of the Royal University of Phnom Penh, (right) Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

Origins of Architecture: Lessons for Contemporary Japan

Having completed all the items on the itinerary without incident, the last place I visited before returning to Japan was the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. This had formerly been a high school, but was converted into a camp under the Pol Pot regime. Numerous people were tortured here, and the place was marked by the cruel past that had cast a dark shadow on Cambodia's modern history. On this day, the Museum was crowded with many foreign tourists, and I saw a small number of survivors who had lived on miraculously speaking to the tourists. However, in Cambodia today, there are children who do not know about the existence of this camp, and the facts are not recorded in textbooks. In what direction is Cambodia headed? In 1999, the country became a member of ASEAN, and welcomed a significant increase in overseas investment. It is entering the modern age at a sudden and rapid pace. Though I was not in Cambodia for long, these developments were evident in the construction sites I saw throughout my stay. According to the staff of the Japanese Embassy in Cambodia, all the aspiring architects in the country say they wish to build modern high-rise buildings in Cambodia. With economic development taking the highest priority, there are concerns that Molyvann's legacy of rooting architecture in Cambodia's tradition, climate, and culture, may be forgotten and not passed down. Nevertheless, having witnessed Cambodia's contemporary architecture up close, I was convinced that it was precisely the pursuit of universality rooted in locality that would become an immense driving force for architecture that provides peace of mind. I also felt that the scenes of happiness I had witnessed and had been produced by Molyvann's architectural works represented the origins of architecture that I hope contemporary Japan will also take to heart. During my stay in Phnom Penh, not only did I have the opportunity to meet with local university faculty members and those in the architectural field, but I also met Japanese architect Yoko Koide. She has continued to devote herself to providing support for the rural regions, including donating three hectors of her privately owned land to Siem Reap in October 2013, the tourist destination that is home to Angkor Wat, as well as designing public junior high schools with the help of construction subsidies. Little did I realize, it was I who had learned many lessons over the course of my stay and been exposed to new perspectives. Though I do not know how I may be able to work together with Cambodia in the future, I do hope to do what little I can to introduce Cambodia's contemporary architecture and its appeal to the world, and to help the people of Cambodia regain pride in their architectural culture and pave the way for the future with confidence.

Hiroshi Matsukuma

Hiroshi Matsukuma

Born in Hyogo Prefecture in 1957. After graduating from the Undergraduate School of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering of Kyoto University in 1980, he joined Mayekawa Associates, Architects and Engineers. In 2000, he became Assistant Professor at the Kyoto Institute of Technology, and Professor of the same university in 2008, where he still teaches today. Matsukuma holds a Ph.D. in Engineering (University of Tokyo). He has been a member of DOCOMOMO Japan since 2000, and representative of the organization since May 2013.

Significant works Matsukuma has authored include Louis Kahn (Maruzen); "Remembering Contemporary Architecture" (Kenchiku Shiryo Kenkyusha); "Who is Junzo Sakakura?" (Okokusha); and "Architecture that Should be Preserved" (Seibundo Shinkosha). He has also coauthored "Rereading: Japan's Modern Architecture" (Shokokusha); "A History of Japanese Architecture" (Bijutsu Shuppan-sha); "Reconsidering Kansai Modernism" (Shibunkaku); "Nuclear Power and Architects" (Gakugei Publishing); "Art Museums and Architecture" (Seigensha Art Publishing); "Kunio Maekawa--Dialogue with Modernity" (ed., Rikuyosha); "The Work of Kunio Maekawa, Architect" (Bijutsu Shuppan-sha); and "The Work of Masato Otaka, Architect" (X-Knowledge), etc.

In addition to serving as the Secretary-General of the Executive Committee for Kunio Maekawa's architecture exhibition to commemorate his 100th anniversary, held in 2005 to 2006, Matsukuma curated the "Modernism Architecture as Cultural Heritage" exhibitions - DOCOMOMO 20 Selections (Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura and Hayama, 2000) as well as DOCOMOMO 100 Selections (Shiodome Museum, 2005). Also he collaborated on numerous architectural exhibitions including Antonin Raymond, Junzo Sakakura, Charlotte Perriand, Seiichi Shirai, Kenzo Tange, and Togo Murano. He is a member of the Executive Committee for the 100th anniversary project for Kenzo Tange, and serves on the steering committee for the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs.

Profile photograph: Sadamu Saito

Keywords

- Architecture

- Japan

- Cambodia

- Switzerland

- Finland

- France

- Phnom Penh

- Le Corbusier

- Vann Molyvann

- Architecture Institute of Japan

- the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

- Great East Japan Earthquake

- Kenzo Tange

- Kagawa Museum

- Kunio Maekawa

- Junzo Sakakura

- Takamasa Yoshizaka

- Yoshio Taniguchi

- Hiroshi Naito

- Angkor Wat

- Khmer

- DOCOMOMO

- Cambodian Mekong University

- Hiroyuki Suzuki

- Tokyo Bunka Kaikan

- Sorbonne University

- Pol Pot

- Alvar Aalto

- William Graves

- Royal College of Art

- Yale University

- Moscow State Technical University

- Institute of Technology of Cambodia

- Cambodia-Japan Cooperation Center

- Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

- ASEAN

- Yoko Koide

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…