The ASEAN-JAPAN "Drums & Voices" Concert Tour: A Unique Collaboration of Traditional Percussion and Vocal Music

Michiru Oshima, Composer

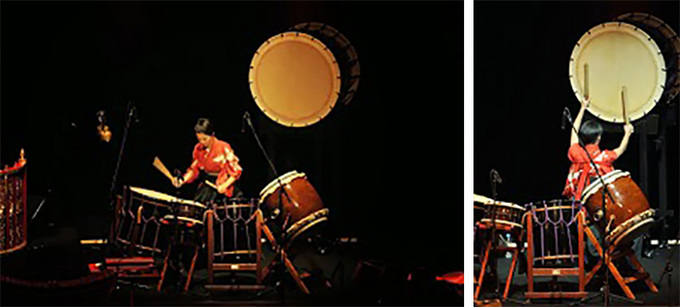

Tsubasa Hori, Wadaiko drummer

The "Drums & Voices" concert tour that traveled to six ASEAN countries and Japan concluded with a December 2013 finale in Tokyo, Japan. Presented in celebration of the 40th anniversary of ASEAN-Japan friendship and cooperation, "Drums & Voices" brought together 12 performers of traditional music from seven countries--Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Brunei, and Japan--to embark on a new challenge of composing and performing music, using just percussion instruments and vocals. The result was a series of stunning performances that brought out the best of each musician's talents and uniqueness. In the following interview, composer Michiru Oshima, who served as the project's music director, and wadaiko drummer Tsubasa Hori, who represented Japan in this multi-cultural ensemble, reflect back on and talk about the recently completed tour.

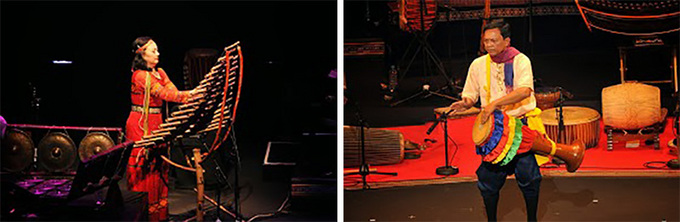

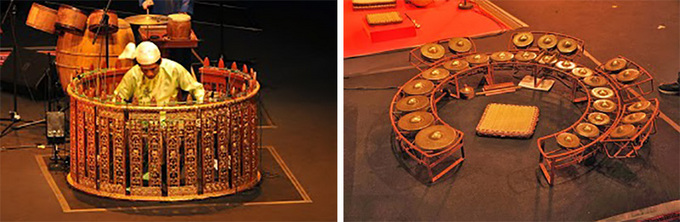

Some of the traditional percussion instruments on tour

(Left) T'rung (Vietnam), (Right) Chaiyam (Cambodia)

(Left) Hsaing Waing (Myanmar), (Right) Kyi Waing (Myanmar)

(Left) Maung Hsaing (Myanmar), (Right) Poengmang Khok (Thailand)

(Left) Kong Hang (Laos), (Right) Rebana (Brunei)

Michiru Oshima Interview

The first step was to get to know each other

──First, tell us how the tour was received.

OSHIMA: The concerts were a tremendous success with a huge turnout, and people really enjoyed themselves. We even had small children dancing to the music. The tour kicked off in Vietnam, where we were greeted with great enthusiasm and the reception was wonderful everywhere else, too, but Cambodia was by far the most responsive. People were fully engaged from the moment the show opened, dancing to the rhythm, clapping and cheering. The reception was exceptionally warm and supportive there. After the show, I was touched to hear someone saying, "I've never been to a concert like this before."

I was also surprised at the enthusiastic reaction of the Thai audience to Laotian songs. You would have thought everyone in the audience came from Laos, the way they broke out into a loud cheer when the Laotian musicians appeared. The overwhelming familiarity with Laotian music in Thailand was a little unexpected, even if Laos is their next-door neighbor. It all made sense when I later visited the history museum in Laos and learned the history and the relations between the two countries.

Good audience reactions build confidence in musicians. Watching the final show in Tokyo in December 2013 I could feel how much each of the musicians matured musically over the course of the project. It had been a while since they had last played together, in October and November in Southeast Asia, but in Tokyo they performed so beautifully as a group that no one could have probably guessed the musicians came from different countries. The effort we had put into the one-month pre-tour workshop and the time spent together on the month-long tour clearly paid off.

──The 12 musicians from seven countries met each other for the first time at the June 2013 workshop in Thailand. Looking back, how would you describe the experience?

OSHIMA: It was tough. As performers of traditional music, they were not very familiar with creating music in collaboration with musicians who come from other countries and have very different backgrounds from their own. So we started off by trying to understand each other's music. In addition, as a music director I needed to get a sense of everyone's strengths and weaknesses. You can't produce a quality performance by giving the same instructions to all 12 musicians; you have to help them play to their strengths, emphasizing their individual advantages. Indeed, the workshop started from zero.

──Was it the first time for the musicians to touch the percussion instruments from other countries?

OSHIMA: Yes. It was the first time for me, too, to see any of the instruments except Japan's wadaiko. Unlike a well-known western musical instrument, say, the violin, you don't get a chance to see a traditional musical instrument unless you go to the country where it originated. All the instruments used in "Drums & Voices" come from Asia, so they have similarities, but at the same time there are many differences, in rhythm and in how they are played. The musicians had to grasp these differences. The hardest part was that the project didn't end with the workshop; we had to present our work to an audience in a concert, which, at first, felt like an enormously daunting task.

──Were the songs you performed written by combining various elements of traditional music?

OSHIMA: Some were written that way, and others we made from scratch. Of the 15 songs performed, half are arrangements of traditional materials and the rest are our originals. Some songs were written by the musicians, others I worked on by myself.

──Your music is marked by graceful melodies and grand scale. Writing songs for percussion instruments must have been a bit of a change for you.

OSHIMA: Yes, I would say so. If it's an orchestra, just have a violinist play a tune and you have music. That doesn't happen with percussion instruments, most of which only make short, bursting sounds. Some do play a melody but don't produce lingering sounds. On the other hand, these instruments generate a great variety of sounds. I discovered that depending on where or how you play it, a single instrument can sound so many different ways.

──What was the most challenging aspect of this project?

OSHIMA: It was communication. Many didn't speak English, so we had no common language among us. It was frustrating that we had to communicate through interpreters. And the musicians were very reserved, which was sometimes a good thing, but not always. They generally held back from speaking their minds. There were times when someone would bring up an issue from way earlier, for instance, about something that was said by somebody else days before. When you work with westerners, you can easily tell what they are thinking from their words or their facial expressions. Apparently, we Asians, the Japanese included, aren't so open. So once I understood that, I made a conscious effort to pay more attention to each member and ask from time to time if everything was all right, if there was anything he or she wanted to share with me. Normally, during studio sessions, which are the main part of my work, I just hand out music sheets and the musicians perform it. That's it. But it didn't work like that here; we had to take the extra step of getting to know each other as people first.

──The musicians must have had strong attachment to the music of their own country.

OSHIMA: They are all artists, which meant each person had his or her own distinct ideas about their music. I'm sure they didn't want to present their country's traditional music in any way that wouldn't satisfy their quality standards. Thus, they felt protective of their traditional music but at the same time wanted to reach beyond it and create something new. It took incredible patience to work and communicate effectively with people having such diverse objectives and views.

Appreciating the importance of dialogue

──In the end, you were able to develop a bond like family and the tour was a great success.

OSHIMA: Thank you. I am pleased to say we managed to reach the stage where we were able to entertain the audience and enjoy ourselves performing for them.

──It's important that the musicians enjoy themselves as much as the audience does, isn't it?

OSHIMA: Yes, because the musicians can't give a good performance if they aren't enjoying themselves. When I write songs, and I do this for all my work, I always ask myself, "Is this song enjoyable for the people who play it?" Musicians are very straightforward. If a songwriter puts a lot of effort into a work, they play it with all their heart. A song written half-heartedly gets played with the same level of detachment. The mind and the body are closely linked, and a musician's feelings are clearly reflected in the performance. So I make it a habit to watch carefully whether the musicians appear to be having fun performing. If there is any sign that they are not, I'll have to review the score.

──If professional musicians focus too much on pursuing music for their own enjoyment, the music can get very technical and not at all appealing to novices.

OSHIMA: It may be. In jazz, for example, a lot of improvisation could be exciting for the musicians but alienating for listeners. That can happen if you leave everything up to the performers. In my case, however, I often score for movies or television, so I have to write music that stirs emotions in the viewers when the music combines with the visual image. To do that, I have to get the musicians engaged as well. The same is true with concerts. I aim to write music that both the performers and the audience can enjoy.

──Now that it's over, what are your thoughts on the concert tour?

OSHIMA: This tour brought together people from different countries, different music, and different musical instruments. We succeeded in collaborating with each other to create new songs without anyone having to compromise. In a way, this is an ideal model of society. If we can do this in music--recognize each other, leverage everyone's strengths and minimize each other's weaknesses to create something new--then we can surely do the same in other areas or endeavors. This project convinced me of that.

──Would you say that was the essence of this project?

OSHIMA: Yes. It takes time to understand each other, but you just have to be patient and keep up the effort. Nelson Mandela, whose death in 2013 was met with an outpouring of grief from around the world, overcame hardships through long, continuous dialogue. We have words and we also have music to help us connect with one another. Mutual understanding can be achieved in various forms and contexts, and it will yield positive results.

──It sounds like the tour drove home the importance of dialogue.

OSHIMA: I believe the fact that we all used different languages amplified the importance of dialogue. When it's just us Japanese, we tend to take each other's understanding for granted and assume we can get our message across without actual words. When I am working in a studio and conducting, I try to observe the musicians playing music in front of me. If anyone looks ill or tired, for example, I suggest a break even if no one asks. But there are things you cannot tell from the outside. So, I now realize that, instead of just assuming how others feel, I should try to communicate more with people. The project also taught me that we should not spare time when making music. A good piece of music takes both time and hard work.

A group of highly distinctive artists colliding with one another!

Tsubasa Hori interview

Astounded by a radically different source of inspiration

──You represented Japan in this project and took on the challenge of making new songs with the musicians from six other countries. How did you like it?

HORI: The workshop in Thailand started with "It's nice to meet you." We all spent time together during the workshop like you do in a camp, eating meals together. That time we spent getting to know each other, right down to our day-to-day lifestyles, was extremely valuable. Usually, with a joint concert or other collaborative event there is very little time for rehearsals. We get three days or so of practice, then it's time to hit the stage. In contrast, in this international co-production the participants were given the time and opportunity to really dig deep into the activity of making music together and we got to know each other as people in the process. The experience was fun and it helped me grow.

──With participants coming from such diverse national backgrounds, did you experience culture shock?

HORI: I was stunned by the wide range of sounds the other musicians created with their instruments and also by the differences in images that gave them musical inspiration. For instance, the musician from Myanmar pictures in his mind a bunch of ripe bananas being hung from a tree or fish jumping up from the sea and translates the scene into music. I guess it is only natural that each of us are inspired by different things, given we come from different cultures, but I found it remarkable all the same.

Another thing that impressed me was, because most of the traditional musical instruments are made from natural materials, the musicians tuned and maintained them on their own, scraping or moistening them. And the simplicity of the instruments meant they could make minor repairs themselves. I was amazed. With wadaiko, it's impossible to replace the leather by myself because it is so big, but still, I learned a lot from their attitude toward their instrument.

──Was it challenging for you to perform with the percussion instruments from other countries?

HORI: It was probably harder for Ms. Oshima, who oversaw this project as the musical director, than it was for us. Different instruments have different characteristics in rhythm, sounds, volume, and etc. It must have been a struggle to achieve the right balance, combining the sounds of multiple instruments without losing their distinct features.

──The concert toured six ASEAN countries. Which country was the most memorable for you?

HORI: Cambodia. At the opening, when each performer introduced his or her country's music using the instruments and songs, the Cambodian audience was clapping their hands as soon as they heard a beat. Everyone was very excited and enthusiastic.

──Ms. Oshima said the same thing, that she was struck by the enthusiasm in Cambodia.

HORI: I have the impression that compared to Japan, people in Cambodia are more connected to traditional music and traditional musical instruments. These things are still an important part of their lives.

──Wadaiko is also a relatively familiar musical instrument for Japanese. Even though they may not have played koto or shamisen, most of them have beaten a taiko drum, I think.

HORI: That's true. Knowing that Japanese people are generally aware of what wadaiko sounds like and how it is played, I was more nervous performing in Tokyo than I was during overseas performances, especially because I am now based outside of Japan.

──In the wadaiko-based song "Yukiusagi," it looked as if you were dancing as you were performing, which added a feminine quality to the powerful taiko sounds. You made a strong impression with the performance. And one can't imagine just how someone of your petite frame could produce such strong drum sounds.

HORI: I get that comment all the time. I started playing wadaiko when I was little, but actually, I'd been more focused on studying western percussion instruments. I am not a practitioner of traditional music that has been handed down through generations. Although I was with the drum group Kodo for 14 years, from 1996 to 2010, I am now based in Belgium, working with artists from a broad range of genres. And I wanted to bring to this tour all that I could offer now, as an internationally-based artist.

Mutual understanding transcends borders!

──Did you personally find the concert tour to be a meaningful experience?

HORI: Very much so. Touring these countries and meeting so many people made me appreciate that, although we come from different countries, we can understand each other and we have many things in common. Those were valuable insights to take home. I found my ASEAN colleagues to be very cooperative; they would always put the group's interest before personal desires. With no clash of egos, everyone got along really well from the beginning to the end. Another big reward of the tour was that I was able to reaffirm my perspective about the role of percussion instruments in folk performing art.

──What do you mean by the role of percussion instruments?

HORI: Percussion instruments provide the rhythm, so I have come to believe their true role is to support other musical instruments. One reason this ensemble worked so well as a group, in my opinion, was that we were all percussionists whose job is to support others. Of all the percussion instruments, wadaiko might in fact be the least inclined to take this supportive role, seeing as how it has established itself as an independent form of entertainment in Japan. I think wadaiko underwent its own evolution in Japan.

──Do you think the experience of the tour will help you in your future career?

HORI: Since I moved to Belgium four years ago I haven't had the opportunity to play with a full set of taiko drums, so this was a very precious experience. From now on, I hope to play wadaiko as often as I can. After all these years I still find percussion instruments very intriguing.

(Interviewer and editor: Keiko Tsuji, article photos: Masayuki Noda)

Michiru Oshima

Michiru Oshima

Composer

Graduated from Kunitachi College of Music, majoring in music composition. Started her musical career as a composer and arranger while still a student, and continues to be involved in a wide range of musical projects, including films, television commercials and programs, animated features, and ambient music. Received the 52nd and 67th Mainichi Film Award for Best Film Score, and the 21st, 24th, 26th, 27th, 29th, and 30th Japan Academy Prize for Outstanding Achievement in Music. Also won the Animation of the Year music award in 2006, and several other prizes, such as the Best Composer Award at the Jackson Hole Film Festival in the United States.

Her CD For The East is currently on sale in France and Japan. Also wrote the musical score for Sayuri Yoshinaga's atomic bomb poetry recitals. Her major works include NHK Taiga Drama Tenchijin, movies Gozilla vs. Megaguirus and Memories of Tomorrow, and anime Fullmetal Alchemist.

Official website: http://michiru-oshima.net/

Tsubasa Hori

Tsubasa Hori

Wadaiko drummer

Born in Kyoto, Japan, Hori started playing wadaiko drums at age 11 and studied western percussion and music theory at Kyoto Horikawa Senior High School of Music. In high school, she was also a drummer in a rock band. After a 14-year stint as a member of the wadaiko drum group Kodo, from 1996-2010, Hori has shifted base to Antwerp, Belgium, where she works on collaborative projects with artists from various genres. Her original music that draws on Japanese rhythm and songs is widely acclaimed in Japan and abroad.

(Photo: Kotori Kawashima)

Back Issues

- 2025.7.31 HERALBONY's Bold Mis…

- 2024.10.25 From Study Abroad in…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…