KENCHIKU / Architecture from Japan

Makoto Shin Watanabe, Architect and professor at Hosei University

Pedro Gadanho, Curator of Contemporary Architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA)

Christian Teckert, Architect and curator, professor at Muthesius Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Germany

Hsieh Tsungche, Assistant professor at Asia University, Taiwan

Taro Igarashi, Artistic Director of the Aichi Triennale 2013, professor at Tohoku University Graduate School

The Japan Foundation and the Aichi Triennale 2013 co-organized an international architecture symposium titled "KENCHIKU / Architecture from Japan," and it was held on August 11, 2013, at Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya, Japan.

Today, Japanese architecture is receiving a great deal of attention abroad. These architects' work does not forcefully assert a Japanese style, but has instead prompted a rediscovery of familiar living spaces, and inspired new cultural exchanges. It is also notable that the work has been received in such a natural way. Given the recent popularity of Japanese architecture abroad, can the Japanese word "kenchiku" (architecture) come to be a universal term like "anime" and "otaku"?

To explore this question as well as the possibilities and challenges of contemporary kenchiku, the panelists engaged in a lively discussion at the symposium.

Relations between art and architecture

WATANABE: My name is Makoto Watanabe and I will be serving as the moderator today. I previously had the opportunity to work on the design of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles under Arata Isozaki and ever since, the relationship between art and architecture--one of the themes of the Aichi Triennale 2013--has been a topic of interest for me.

WATANABE: My name is Makoto Watanabe and I will be serving as the moderator today. I previously had the opportunity to work on the design of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles under Arata Isozaki and ever since, the relationship between art and architecture--one of the themes of the Aichi Triennale 2013--has been a topic of interest for me.

That's because in Japan, architecture is considered to be engineering and therefore is taught as an engineering discipline at universities, while in Europe and the United States it belongs to the fine arts department. The distinctive Japanese practice of emphasizing the engineering dimensions of architecture has been a familiar subject of discussion.

Regardless of the differences in definition, Japanese architecture has been receiving critical acclaim abroad. To illustrate, the recently completed Louvre-Lens, the Musée du Louvre's new annex, was designed by SANAA, a studio of the architectural duo Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, and Shigeru Ban was awarded the contract to design the Centre Pompidou-Metz. Clearly, despite its strong links with engineering, Japanese architecture has found international appreciation in artistic fields.

Today, we have invited three guests--an architect, a curator, and a scholar-- from the United States, Europe and Asia to discuss, based on the current state of Japanese architecture, its reception and recognition in each of their countries. Following the presentations the 2013 Aichi Triennale's artistic director Taro Igarashi will join us in a panel discussion to explore the future outlook of Japanese architecture and its possibilities and challenges in the artistic fields.

Would it be more fitting to call Japanese architecture Kenchiku?

WATANABE: Before starting with the presentations, let me first give an overview of the symposium's topic, "KENCHIKU / Architecture from Japan."

Celebrating the centennial of the birth of the architect Kenzo Tange, the Kagawa Museum presented a retrospective exhibition entitled "Kenzo Tange: Tradition and Creation--From Setouchi to the World" from July 20 to September 23, 2013. Recognizing Kenzo Tange to be the first Japanese architect who succeeded in gaining an international acclaim in the field, it is generally accepted that the succeeding generations of architects including Arata Isozaki, Tadao Ando and Toyo Ito have been following his footsteps and establishing Japanese architecture on the world map. At the same time, there may be an emerging alternative perception in the understanding of what Japanese architecture stands for and that is one of the topics for discussion today.

The term Kenchiku in the symposium title--written in katakana, which I guess strikes some people as strange-- arises from this newly formed perception. This view suggests that architecture may be experiencing the same phenomenon that has occurred with other aspects of Japanese culture such as manga, anime, and otaku. One could ironically ask, "What could be more suitable to house anime-crazed otakus than a piece of Kenchiku?" It may be mere speculation, but aren't we seeing an emergence of a Japanese architectural movement that is best called Kenchiku, a specialty entirely different from the discipline the English translation of which is "architecture?"

Many of Japan's post-war architectural projects centered on very small houses. Some examples include Makoto Masuzawa's minimum house in 1952 and Hitoshi Abe's 9-tsubo house in 2004. What's more, the 3D spatial and minimum houses introduced by Kiyoshi Ikebe in 1950 and, more recently, the 2011 Core House project of Atelier Bow-Wow. An attempt to compare and contrast the works of these architects who took an interest in and worked on compact homes may provide an insight into the development of an alternate form of Japanese architecture. I shall now give the floor to the first speaker.

Interest in Japanese architecture inspired by Kurosawa and Ozu

GADANHO: My name is Pedro Gadanho and I would like to first share with you my view on Japanese architecture. My interest in Japanese architecture started with Akira Kurosawa's film, Ran. I was drawn to the spatial use of and the relations between interior and exterior in the Japanese buildings. Set in the Warring States period of Japan, the film offers a striking view of castles in which the inside and the outside appear contiguous. It occurred to me that the distinctive characteristics of Japanese architecture are this lack of a clear boundary between interior and exterior and the sense that the interior is an integral part of the landscape.

GADANHO: My name is Pedro Gadanho and I would like to first share with you my view on Japanese architecture. My interest in Japanese architecture started with Akira Kurosawa's film, Ran. I was drawn to the spatial use of and the relations between interior and exterior in the Japanese buildings. Set in the Warring States period of Japan, the film offers a striking view of castles in which the inside and the outside appear contiguous. It occurred to me that the distinctive characteristics of Japanese architecture are this lack of a clear boundary between interior and exterior and the sense that the interior is an integral part of the landscape.

Another film director who had an impact on me was Yasujiro Ozu. His 1953 film, Tokyo Story, depicts Japan's post-war recovery and aspects of social relations and features some very unique camera angles and shots. When shooting the interior of a house, for instance, Ozu placed the camera in a very low position, connecting the interior to the outside world which had the effect of bringing into the screen the view of ever-changing modern cities. This connection also resonates with Junichiro Tanizaki's essay on Japanese aesthetics, Ineiraisan (In Praise of Shadows).

The interior-exterior relationship I just described can be found in Tadao Ando's Row House in Sumiyoshi. Almost three decades separate the society portrayed in Ozu's film and Ando's house, but the spatial feel is very similar. One unique aspect of Ando's style that Westerners often find puzzling is the inclusion of external natural elements such as climate in private quarters.

Innovations rooted in tradition

GADANHO: I believe the Metabolism movement has played a critical role in Japanese architecture. Metabolism, which sought to represent organic growth through architectural innovations, was the last avant-garde movement in the true sense.

The Metabolists were architects with traditional backgrounds. Regrettably, many of their designs could not leave the drawing board. All the same, attempts at innovation based on tradition are extremely important because they encourage the challenging of established architectural theories and ideas. This also relates to the philosophies of Zen.

You might say it is a personal defeat of Kisho Kurokawa that his Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo will have to be demolished. The underlying idea behind the project, of maintaining or renewing a structure by replacing its parts, is a significant form of protest against the wastefulness and destructiveness characteristic of capitalism. Kurokawa's philosophy calls to mind the renovation of Japanese shrines, which are restored to their precise original condition. It gives us much to think about that Kurokawa dared to offer a vision of transient, impermanent architecture at a time when appetite for urban development was much stronger than it is today.

International impact of Japanese architecture

GADANHO: Let me now talk about what I find interesting in contemporary Japanese architecture. Since last year I have been working at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), studying trends and developments of architecture abroad. With regards to Japan, I'd like to cast a spotlight on private houses.

There are many different types of homes, from Jun Igarashi's House M to Keiichi Hayashi's House in Osaka, and they all share a modern, experimental quality and the traditional Japanese ideas about space. At a glance, you see a nondescript exterior, just like an anonymous house in a cramped residential area. In contrast to the simple exterior that gives it the look of a minimal object, the interior is tremendously dense and complex. The design reconfigures the relations between the inside and the outside while at the same time providing new meanings in terms of the structure's relationship with the wider world. Creating as open a space as possible in crowded city dwellings is a universal concern of architects the world over and the examples I mentioned embody Japan's unique solutions to this problem.

The Japanese trend has had an influence on architects in other countries mainly through publications such as El Croquis, an international architecture magazine that featured Toyo Ito and Kazuyo Sejima in the past issues. The Portuguese architecture practice fala atelier, for example, appears to draw inspiration for their designs from Ryue Nishizawa's works.

The project designed by the Portuguese architecture practice fala atelier

©Alvenarida Modular Social Housing, Lisbon. fala atelier

One gets the impression that in Europe and the United States there is a prominent number of magazines articles or books on Japanese architecture being published. This rapid evolution of the media environment will also serve to amplify the international influence of Japanese architecture.

The hybrid blend of East and West, of the traditional and the modern

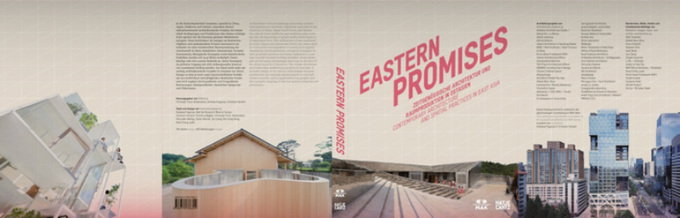

TECKERT:My name is Christian Teckert. This year I curated an exhibition titled "EASTERN PROMISES: Contemporary Architecture and Spatial Practices in East Asia" at the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art (MAK) in Vienna, Austria - in collaboration with the artist Andreas Fogarasi. Showcasing architectural projects from Korea, China, Taiwan, and Japan, the exhibition investigated the new social aesthetics emerging in East Asian contemporary architecture. A large part of the show was devoted to Japanese architecture. In recent years numerous books have been published on its concepts and theories and Japan plays a leading role in the region's architecture scene. Beginning with a discussion about the origins of modernist architecture, and you could say the intense dialogue on Japanese architecture has been going on for almost a century. Through these dialogues Japanese architecture has evolved into a hybrid combination of East and West, of the traditional and the modern, which is a truly unique situation.

TECKERT:My name is Christian Teckert. This year I curated an exhibition titled "EASTERN PROMISES: Contemporary Architecture and Spatial Practices in East Asia" at the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art (MAK) in Vienna, Austria - in collaboration with the artist Andreas Fogarasi. Showcasing architectural projects from Korea, China, Taiwan, and Japan, the exhibition investigated the new social aesthetics emerging in East Asian contemporary architecture. A large part of the show was devoted to Japanese architecture. In recent years numerous books have been published on its concepts and theories and Japan plays a leading role in the region's architecture scene. Beginning with a discussion about the origins of modernist architecture, and you could say the intense dialogue on Japanese architecture has been going on for almost a century. Through these dialogues Japanese architecture has evolved into a hybrid combination of East and West, of the traditional and the modern, which is a truly unique situation.

Exhibition views at "EASTERN PROMISES," Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art (MAK) in 2013. It showed projects by among many others SANAA, Kazunari Sakomoto, Riken Yamamoto as well as Shanghai-based design practice KUU (Satoko Saeki and Kok-Meng Tan) and highlighted the cross-cultural, cross-border potentials of Japanese architecture.

Let me now discuss the exhibition in more detail. The first thing we considered in planning this show was exhibition design--how can we effectively demonstrate the focus on contemporary East Asian architecture, Japanese architecture in particular? We ended up using free-standing displays, reminiscent of the traditional Japanese screens known as byobu, arranged in a grid based on the axonometric projection (a representation of a three-dimensional object placed at an angle to the plane of projection) which relate to painted folding-screens like the screen titled Rakuchu rakugai zu (Scenes in and around Kyoto). An axonometric perspective has no definite center so everything that appears in the drawing, from buildings and nature to people, is given equal significance. This non-hierarchical Japanese spatial practice, in stark opposition to western approaches, is common throughout East Asia. It can even be traced back to China 2,000 years ago.

A contemporary form of axonometric expression also can be found in Atelier Bow-Wow's drawings. This was a critical finding for us on the curatorial team because the complexity and the hybrid nature of design is represented in this unique drawing that is also a study of the issue of the limitation of space in Asia's highly dense megacities.

Research from this perspective has brought to light the complex interior-exterior relationship and the private-public dynamics that Pedro talked about earlier. This dichotomy is not so straightforward in Japanese architecture. In a private home, for example, the duality shifts and changes, functioning as a symbol of the outside world and at times a soft boundary. There are times when a house has intermediary space, a bridge between the work space and the living space. There is also the relationship between the traditional tatami room and engawa (the narrow verandah adjoining the tatami-room): This exterior platform is open, not only to interpretation but also in practical terms. This equivocal nature of architectural elements can be found in buildings in other East Asian countries as well as in Japan.

The close connection between architecture and society

The "EASTERN PROMISES" exhibition introduces around 70 architectural projects, over half of which has turned out to be Japanese. I'd like to discuss some of the works briefly.

Kazuyo Sejima's SHIBAURA HOUSE is one key project. In the West, works by Sejima and Nishizawa's SANAA are often described in association with hyper-aesthetics, minimalism, and diagrammatic abstraction. But what makes SHIBAURA HOUSE special in addition to all this is that it serves as a ground for a radical space-sharing experiment, it represents a new kind of public space in different graduations. The building that formerly housed a publishing firm was remodeled into an open, public workshop space designed to accommodate a variety of events and activities including dining and yoga.

A project having a similar direction to SHIBAURA HOUSE is Ryo Abe's Shima Kitchen located on Teshima, a rural island in western Japan. A low-budget renovation project, the open kitchen that was once an old house is canopied with a sloped roof and provides a welcoming venue for dining and conversation. Abe uses architecture as a means to create dialogue by moving away from its meticulousness and focusing instead on efficiency, social issues and community building. He invited local villagers to participate in the designing and the building processes, which he considered to be part of the project.

In addition to these, "EASTERN PROMISES" introduces crucial works on the urbanistic dimension of Japanese Architecture by Kazunari Sakamoto and Riken Yamamoto, among others.

Research on Japanese and Asian architecture has revealed the architects' interest in experimenting with new social structures and building a new type of community. In the East Asian context, architecture is intimately connected to society. Asian architecture is open and horizontal; it exemplifies a venue for social interactions and embodies new possibilities.

The impact of Japanese architects on Taiwan

HSIEH: My name is Hsieh Tsungche. Today I'd like to talk about the activities of Japanese architects in Taiwan. Currently, a number of new building projects designed by Japanese architects are under construction in Taipei and Taichung. The history of Taiwan-Japan relations in terms of architecture goes back almost 100 years to the Presidential Office Building designed by Uheiji Nagano during the period of Japanese rule of Taiwan. More recently, Kenzo Tange's office designed the Eslite Bookstore in the 1990s.

HSIEH: My name is Hsieh Tsungche. Today I'd like to talk about the activities of Japanese architects in Taiwan. Currently, a number of new building projects designed by Japanese architects are under construction in Taipei and Taichung. The history of Taiwan-Japan relations in terms of architecture goes back almost 100 years to the Presidential Office Building designed by Uheiji Nagano during the period of Japanese rule of Taiwan. More recently, Kenzo Tange's office designed the Eslite Bookstore in the 1990s.

The most prominent Japanese architect in Taiwan in the 21st century is Toyo Ito. His works include the Main Stadium for the World Games 2009 in Kaohsiung and Taichung Metropolitan Opera House now under construction. The latter, a progression of his signature work, sendai mediatheque, has a very complex structure that evokes an image of some animal's skeletal system, with a series of horizontal and vertical tubes penetrating the building. This structural system I believe is based on the traditional Japanese spatial strategy of connecting the inside and the outside that Pedro mentioned. The Opera House project has had a powerful impact on Taiwanese architectural firms, giving us much to learn from.

The construction site of Taichung Metropolitan Opera House designed by Toyo Ito

Toyo Ito has indeed been closely connected with Taiwan. The building of the National Taiwan University College of Social Sciences is yet another of his projects. The library area is especially striking with its fluid space created using an algorithm. The glass opening on the roof and other features are said to have presented considerable construction challenges, but the completed building holds the viewer in awe with its sheer beauty.

In fact, when I was having a discussion with the other panelists last evening, the phrase "kawaii (pretty) architecture" came up. This university building is clearly a good example of a kawaii architecture. If you study in such a building maybe your whole outlook on the world will be rosier--you never know.

The next work I'd like to discuss is Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport Terminal 1 designed by Norihiko Dan. It had its grand opening in July 2013, and was not built from scratch but remodeled using knowledge and technology of expansion from traditional Japanese architecture. The Sun Moon Lake Administration Office of Tourism Bureau is another of Dan's projects. Dissolving into a landscape characterized by striking slopes and curves, the buildings are in complete harmony with the environment.

Let us now turn to the next project, one of which I am a part, a resort hotel to be built on the Penghu Island located in the Taiwan Strait. A collaborative project of Norisada Maeda's firm, N Maeda Atelier, and my practice, Atelier SHARE, this endeavor is remarkable for its application of brainwave research findings in the designs. We are looking to create an organic interior landscape by simulating the brainwave pattern on the shape of the floor.

Another work by a Japanese architect is the Ando Art Museum located on the Asia University, Taiwan campus. Designed by Tadao Ando, the museum is set to open in October 2013.

The architectural model of a joint project by N Maeda Atelier and Atelier SHARE, now underway.

The final work I would like to talk about is Sou Fujimoto's winning proposal in the international competition for Taiwan Tower in 2011. The Eiffel Tower was the object that embodied the spirit of Paris, the world's cultural capital in the 20th century. In designing Taiwan Tower, Fujimoto emphasized the environment over the object. The tower's roof-top garden, suspended 300 meters above the ground supported by hundreds of steel beams, reminds us of the Legendary Island in the manga ONE PIECE. It remains to be seen how long the project will take to build, but the finished work will no doubt be a tower like no other.

The exhibits at the "Logia Architecture" exhibition curated by Hsieh Tsungche (KIANTIOK Museum, Tainan, 2012). The exhibition also featured works by the Tainan-based architectural firm Open United Studio, one of the exhibitors at the Aichi Triennale 2013.

Architecture beyond modernism

WATANABE: Thank you, gentlemen. Following the presentations by the three panelists I'd like Mr. Taro Igarashi to make some remarks.

IGARASHI: I would like to pick up on the issue of the Japanese term Kenchiku raised by Mr. Watanabe earlier. The term originated in the Meiji period, when historian and architect Chuta Ito translated the English word "architecture" into Japanese. Japan had of course experienced an influx of architectural culture since way before the modern era. The Japanese have for centuries absorbed the latest wooden building technologies from the Chinese continent and the Korean Peninsula, adapting and refining them to suit their own needs and interests.

IGARASHI: I would like to pick up on the issue of the Japanese term Kenchiku raised by Mr. Watanabe earlier. The term originated in the Meiji period, when historian and architect Chuta Ito translated the English word "architecture" into Japanese. Japan had of course experienced an influx of architectural culture since way before the modern era. The Japanese have for centuries absorbed the latest wooden building technologies from the Chinese continent and the Korean Peninsula, adapting and refining them to suit their own needs and interests.

In the meantime, we have a situation where the contemporary Japanese architecture that Mr. Watanabe called Kenchiku is making a strong presence in the international architectural scene. The Museum of Modern Art, New York selected Yoshio Taniguchi, for example, to expand and redesign its buildings. Also in New York are buildings designed by Jun Aoki and Junya Ishigami, whose works are featured in the Aichi Triennale 2013, and SANAA's involvement in New Museum of Contemporary Art is all too well known. Japan is now sending numerous architects abroad to work on projects all around the globe.

The presenters all cited the integration of inside and outside space and the diminished boundaries as characteristics of Japanese architecture. If I may add one more, it would be the aspiration for buildings of extreme thinness and slimness in spite of the country's earthquake-prone geology.

If you really think about it, however, the ideal of modernist architecture must have also been to depart from the masonry construction (the building structure of piled up stones and bricks) of the pre-modern era and create light, open space free of walls. Embracing, and going beyond the much-discussed similarities between traditional Japanese architecture and modernist architecture, one could argue that contemporary Japanese architecture has accomplished modernism's overarching goal in the most extreme sense. And I'd like to ask this question to the presenters--is this slim and light orientation perceived as a characteristic of Japanese architecture by overseas viewers?

GADANHO: American and European architecture has been influenced by the extreme transparency and lightness in Japanese architecture, so, yes; these qualities are recognized as its feature. There are two ways to interpret these extremities: the first is that they arise from economic needs and the second that they result from artistic experimentation. The socio-economic concerns run in parallel to the aesthetic pursuits, a phenomenon found throughout the world.

People often ask me to give an example of the most interesting modern architecture in the United States. But interesting in what sense, I wonder. Should a piece of architecture be assessed from the economic dimension or for its experimental and innovative character? The likely answer is "Both." The economic and the experimental reflect each other like images on a mirror; one influences the other and vice versa. And that is exactly the kind of environment that fosters innovative changes.

TECKERT: As Pedro just pointed out, there is a division between experimental art and commercial architecture. What is interesting in Japan is the area in between. On the one hand you have a radical approach that has the feel of a typology experiment or that takes minimal space to the extreme and on the other you have a more moderate approach. Sou Fujimoto is the prime example.

HSIEH: The acceptance of Japanese architects in Taiwan can be attributed partly to historical circumstances but also to the high quality guaranteed by the made-in-Japan brand and the sensitivity to natural environment. Elegant curves and the duality of approaches mentioned earlier strike a chord with the Taiwanese. You can say Japanese architects are fantasy makers.

Architecture of the tremulous land

WATANABE: Finally, I'd like to ask each presenter to give a brief comment. The Aichi Triennale 2013 chose natural disaster as its theme and was titled "Awakening--Where Are We Standing?--Earth, Memory and Resurrection." What are your thoughts on Japanese architecture in relation to the fact that, as Mr. Igarashi mentioned earlier, Japan is prone to natural disasters?

GADANHO: Frequent natural disasters have instilled such factors as the Zen philosophy, transience, and fluidity into Japanese architecture. It is divorced from the Western belief that buildings are meant to last. In the capitalist society we live in, many things are temporary. The temporary elements in Japanese architecture will become increasingly relevant.

TECKERT: In the course of our research our team spoke with dozens of Japanese architects and artists about the circumstances in Japan after the earthquake disaster. I was most impressed that almost all of them had been involved, one way or another, in reconstruction efforts or some type of project in the Tohoku region. Some had worked on a collaboration project with local artists; others had joined in the effort to re-make existing communities.

These developments represent architectural renaissance. A great opportunity presented itself in the aftermath of a crisis, and in the midst of it all architecture gets to re-create itself. And while it does so, we will see new ideas and new creativity emerging.

HSIEH: The theme "Awakening" reminds me of the 921 earthquake that hit Taiwan in 1999. I don't want this to be taken the wrong way, but I think of an earthquake as part of Mother Nature's metabolic process. It is important, and takes tremendous courage, to begin a new architectural thinking in the aftermath of the upheaval.

WATANABE: Thank you very much. Mr. Igarashi, would you like to make some comments?

IGARASHI: Mr. Watanabe opened the discussion by pointing out that one of the characteristics of Japanese architecture was its affiliation with the engineering discipline, and interestingly enough, the panel also noted the relations between engineering and design.

With more time I would have liked to explore the intriguing phrase "kawaii (pretty) architecture" which may relate to the term Kenchiku. The word kawaii stirred up debate in the Japanese architectural community several years ago when it became part of the architectural vocabulary, used as evaluation criteria. Given another opportunity I would certainly like to hear candid thoughts on this development from European and American perspectives.

It is my opinion that this sense of kawaii developed in the post-modernist period as a direct reflection on the modernist qualities that were unaccommodating, inimical to human beings. In other words, that is the way of thinking that buildings should be more pleasing and endearing to people. And in the Japanese context, it might be this idea that prompted the birth of kawaii architecture.

*This article is composed of edited excerpts from the symposium transcripts.

(Symposium photos: Ikumasa Hayashi, Editor: Taisuke Shimanuki)

Makoto Shin Watanabe

Makoto Shin Watanabe

Architect, professor of the Hosei University, Faculty of Engineering and Design

He established ADH Architects with Yoko Kinoshita in 1987. He worked at the Arata Isozaki & Associates from 1981 to 1995, and he involved in the design of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the Brooklyn Museum in New York City. He is a recipient of the Prize of the Architectural Institute of Japan in 2012.

Pedro Gadanho

Pedro Gadanho

Curator of Contemporary Architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA)

Since assuming his position as curator at the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, he curated the exhibition "9+1 Ways of Being Political" and has been responsible for the Young Architects Program. He is the author of Arquitetura em Público, a recipient of the FAD Prize for Thought and Criticism in 2012.

Christian Teckert

Christian Teckert

Vienna-based architect, curator, lecturer, writer in the realm of architecture, urbanism and spatial theories

In 1999, he established the Office for Cognitive Urbanism with one partner in 1999 and as-if berlin wien with two partners in 2001. Since 2006 he is a professor for Spatial Strategies at the Muthesius Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Kiel/Germany. He co-edited the book Negotiating Spaces in 2010 and Eastern Promises in 2013.

Hsieh Tsungche

Hsieh Tsungche

Assistant professor of Interior Architecture department, Creative Design College of Asia University, Taiwan

In 2010, He formed the LPA (Little People Architects) architecture federation. He is also the director of Atelier SHARE. In 2012, he curated the exhibition "Logia Architecture," KIANTIOK Museum, Tainan. In 2010, he published Pioneer Forever: The Great Architect Toyo Ito.

Taro Igarashi

Taro Igarashi

Artistic Director of the Aichi Triennale 2013, professor of Architecture and Building Science, Tohoku University Graduate School of Engineering

From 2007 to 2009 he was a member of the Arts Encouragement (Fine Arts Division) Recommendation Committee of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and was Commissioner of the Japan Pavilion at the International Architecture Exhibition, the Venice Biennale in 2008.

Keywords

- Anime/Manga

- Architecture

- Economics/Industry

- Natural Environment

- International Exhibition

- Taiwan

- China

- Japan

- United States

- Portugal

- Hosei University

- Museum of Modern Art New York

- MoMA

- Asia University Taiwan

- Aichi Triennale 2013

- Tohoku University

- Aichi Arts Center

- Arata Isozaki

- Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles

- Kazuyo Sejima

- Ryue Nishizawa

- SANAA

- Musée du Louvre

- Shigeru Ban

- Pompidou Centre

- Kenzo Tange

- Kagawa Museum

- Tadao Ando

- Toyo Ito

- otaku

- Makoto Masuzawa

- Hitoshi Abe

- Kiyoshi Ikebe

- Atelier Bow-Wow

- Akira Kurosawa

- Yasujiro Ozu

- Junichiro Tanizaki

- Metabolism

- Kisho Kurokawa

- Jun Igarashi淳

- Keiichi Hayashi

- fala atelier

- Ryue Nishizawa

- Austrian Museum of Applied Arts/Contemporary Art

- MAK

- Kyoto

- Scenes in and around Kyoto

- Axonometricク

- Ryo Abe

- Kazunari Sakamoto

- Riken Yamamoto

- Uheiji Nagano

- Taichung Metropolitan Opera House

- sendai mediatheque

- National Taiwan University

- Norihiko Dan

- Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport

- Sun Moon Lake

- Sun Moon Lake Administration Office of Tourism Bureau

- Norisada Maeda

- N Maeda Atelier

- Atelier SHARE

- Ando Art Museum

- Asia University Taiwan

- Sou Fujimoto

- Taiwan Tower

- Paris

- Eiffel Tower

- ONE PIECE

- Chuta Ito

- Yoshio Taniguchi

- Jun Aoki

- Junya Ishigami

- Capitalism

- Great East Japan Earthquake

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…