A Revised Sketch of Postwar Art: Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Yuri Mitsuda

Art critic

Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde was presented at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, between November 18, 2012 and February 25, 2013, aiming to show the energy of the avant-garde art, generated when multiple media and people intersected in the city of Tokyo during the remarkable period of high economic growth. This was an ambitious exhibition, encompassing many mediums: architecture (Metabolism), music (graphic scores), performance, graphic design, photography, and film. The writer, who contributed an article entitled, Trauma and Deliverance: Portraits of Avant-Garde Artists in Japan for the exhibition catalogue, was present at the opening reception in New York.

An exhibition of postwar art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

In the exhibition, over 40 artists were represented, from Okamoto Tarō to Haraguchi Noriyuki--from the prewar generation to the postwar baby boomers. Three of the artists present at the opening, Shinohara Ushio, Iimura Takahiko and Lee Ufan, were eagerly sought for their comments. Other artists represented in the exhibition included Ikeda Tatsuo, Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, On Kawara, Nakamura Hiroshi, Nakanishi Natsuyuki, Akasegawa Genpei, Kikuhata Mokuma, Ay-O and Hosoe Eikō, all active from the 1950s to the present day.

By getting to know what these artists were doing now in their many spheres, I was able to feel that the 1950s were a radiant, familiar land. But in recent years, more and more of the art critics contemporary with the Japanese postwar art, and the artists presented in the exhibition, including those whom I was able to learn from directly, have now passed away and thereby a sense of gaining a first-hand understanding of the art must change.

More than half a century has passed since the beginning of the 15 years covered by the exhibition. It was when Japan faced the ignominy of unconditional surrender, and entered a lengthy era of conservative government (the so-called 1955 system), which soon turned into a period of high economic growth. This was also the time during which a war-torn nation had recovered and hosted the 1964 Summer Olympic Games in Tokyo and the 1970 World Expo in Osaka, and eventually gained a place in the world as an advanced economy. So it was all the more significant that the tense years of the Cold War, in between the Korean War and the Vietnam War, saw the emergence of anti-war protests against the two renewals of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty in 1960 and 1970. The 15 years encompassed almost all of the background on which the so-called "postwar art" emerged in Japan.

So this, of course, is not unrelated to Japan's postwar art. In my article for the exhibition catalogue, I maintained the view that the trauma of defeat became the driving force behind the postwar art, and I saw this as artistic action demonstrating the wish for social change. Even with only a slight difference in their ages, the artists had widely varying experiences and feelings towards defeat. I attempted to describe what the individual artists aimed for, as mentioning their relationships with society and the changes in artistic expressions and actions.

Similarities with American art of the same period

One point that should not be overlooked is the fact that the period when the American influence on Japanese art was growing strong coincided with the time American contemporary art began to gain critical acclaim in Europe. From 1965 to 1966, MoMA exhibition The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture toured throughout the United States, proving the contemporaneous nature of Japanese and American art. One after another, American curators and museum directors, as well as artists like Jasper Johns, visited to Japan, while Japanese art critics like Tōno Yoshiaki made frequent trips to the United States and wrote articles on American art for Japanese magazines. And many Japanese avant-garde artists managed to fulfill their dream of going to New York.

If a retrospective of postwar art were to be held in New York in 50 years' time, this fact of the merging interests would surely be one of the focal points. It has to be said, though, that in Tokyo 1955-1970 the representation of the postwar Japanese-American interchange was only limited to Shinohara Ushio's "Imitation Art" series, which was inspired by the Fluxus movement and Robert Rauschenberg. In addition, it did not mention about connections with China's woodblock printing of the mid-20th century, and the viewpoint of Korean artists like Cho Yan Gyu who lived and worked in Japan. MoMA's Associate Curator Doryun Chong (a Korean American), who was responsible for organizing this exhibition, said that the idea was to bring out the independent characteristics of the Japanese art, and to cover the 15 years in diagram form, dividing the exhibit area down the middle, and positioning the works to the right and left. By emphasizing the activities of artists' collectives in one section and by grouping together extant pieces, without focusing exclusively on the works of individual artists, the exhibition aimed to overview the transitions of the themes in postwar art. Details of an explanatory nature, such as written comments, period background and data on the artists, were allocated to the exhibition catalogue, and the actual exhibition areas were free of such annotations.

The human figure in the 1950s

Since the gallery space was limited in relation to the expansive nature of the exhibits, the composition of the exhibits had been thoroughly considered and, as a result, kept compact.

Room 1 began with Okamoto Tarō's Law of the Jungle (Mori no okite), and 1950s works rendering the human figure. They represented efforts to grapple with reality, such as Hamada Chimei's Elegy for a New Conscript (Shonenhei aika), an etching series based on his experiences of the war; Ikeda Tatsuo's pen drawings depicting the changes wrought on people by defeat, the occupation and conflicts over the presence of U.S. military bases; Nakamura Hiroshi's trilogy that predicted, in tilting perspective, revolution. In contrast, the works of Nakanishi Natsuyuki and Maeda Jōsaku were more abstract, presenting human figures as proliferating substance. In the politically shaken 1950s, the population explosion and urban chaos became urgent problems. That was the theme put forward by Metabolism's A Plan for Tokyo that dominated the entrance to the exhibition.

Gutai and Jikken Kōbō/Experimental Workshop; and Hi Red Center and Anti-Art

Rooms 2 and 3 contained a digest of works by Gutai (Gutai art association, an avant-garde group of young artists formed under the leadership of Yoshihara Jirō) and Jikken Kōbō (an artists collective, founded by poet Takiguchi Shūzō). Works displaying the constructivist elements of the Jikken Kōbō members were arranged to contrast with the humorous experimental works of paintings, photographs, films and sculptures of the Gutai artists. And it may not have been obvious at a glance that Jikken Kōbō members derived much of their inspiration from the long hours spent at the occupation forces' CIE library to gain information on contemporary European and American art. A section was also devoted here to graphic scores and Yoko Ono's instruction art, from MoMA's substantial Silverman Fluxus Collection.

In Rooms 4 and 5, materials on the Hi Red Center (an avant-garde artists' group founded in 1963 by Takamatsu Jirō, Akasegawa Genpei and Nakanishi Natsuyuki) were arranged opposite the section on "Anti-Art". Tokyo 1955-1970 probably placed the greatest emphasis on the Hi Red Center which engaged in guerilla-type performances in Tokyo to "stir up" everyday life. Shigeko Kubota's links with Fluxus caused her to leave Tokyo and the Hi Red Center and go to New York, where a separate trade-mark banner was created, and re-enacted her stage performance. One of the main images of this exhibition was Shigeko Kubota's map in English of the Hi Red Center's activity locations in Tokyo. Arranged at the entrance, opposite A Plan for Tokyo, it showed the intent of avant-garde artists to revolutionize Tokyo from the inside, in contrast to the architects' bird's-eye view of reconstruction.

On the opposite side, the area was devoted to "Anti-Art" objects by Takamatsu Jirō, Arakawa Shūsaku and others. Due to the confined exhibiting space, however, only small pieces or incomplete parts were on display, so they had the effect of looking like mere samples of "Anti-Art", rather than the real thing. The highlighted works of this whole exhibition included Kudō Tetsumi's 1962 installation and Kikuhata Mokuma's Slave Genealogy, placed on the platform in the middle. Since most large, installation-type works from the sensational Yomiuri Indépendent exhibitions (an annual, non-juried salon) no longer exist, they can now only be witnessed in reconstruction like the Kikuhata work. Kudo's original installation does remain, and it now belongs to Doryun Chong's former workplace, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

The 1960s: Pop art paintings, and 3-dimensional spectacles that lead to Mono-ha (School of things)

The next two sections, Rooms 6 and 7, contained the mid-1960s pop art paintings of Tateishi Kōichi (Tiger Tateishi), Nakamura Hiroshi, Shinohara Ushio and others. They are followed by 3-dimensional works of the late-1960s leading to Mono-ha by Takamatsu Jirō, Lee Ufan and Narita Katsuhiko. The contrast between Mono-ha exhibits, which could be said to be deconstructional sculpture, and kitsch, pop paintings was treated in a fresh perspective that has not been presented before. However, we should not overlook the slight age difference between these artists: The fact that most of the 3-D works within the context of Mono-ha were produced by painters sees deconstruction of a genre as a development of another in a continual flow, rather than a comparison of opposites. If, after looking at the works of the "Anti-Art" group, you might view them as a comeback of paintings and 3-dimensional works, in other words, your interpretation would be displaced in the flow.

Power of urban reproductive media

The last, darkened room was filled with urban chaos. Sketches by the Metabolists such as Kurokawa Kishō; the graphics and animation of Awazu Kiyoshi and Yokoo Tadanori; the illustrations of Nakamura Hiroshi and Katsuragawa Hiroshi; collages by Akasegawa Genpei; Matsumoto Toshio's films; a documentary of Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension) performances; and photographs of the Vivo and Provoke cooperatives.

Collaborations born of the extensive networks built up by the artists included printed matter, films, and various urban, reproductive media. Although there was a 10-year time lag between Vivo and Provoke, their masterpieces of postwar photography were grouped together anonymously, and so I felt reluctant to see them in that way. Still, since the other sections were so efficiently organized, perhaps this contrastive display exuded its own energy.

Reassessing the "postwar" period itself

Through the exhibition, we have come to realize that the Museum of Modern Art was in possession of such a substantial collection of postwar art. It bore witness to the history of mutual interactions between Japan and the United States and to the recent increase in the value given to postwar art.

This exhibition came almost 20 years after the Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky exhibition covering all areas of Japanese postwar art, which was held at the Guggenheim Museum and other venues around the United States. That exhibition catalyzed numerous other postwar art exhibitions around the world. The Gutai art association has given presentations in many countries and the Mono-ha is also attracting attention in recent years, with solo shows by Tanaka Atsuko and Lee Ufan, among others. The growing assessment of postwar Japanese art has been accompanied by the easier access to information. The culmination of this interest in knowing more about the artists and their works has been made manifest as a revised sketch of postwar art in this exhibition at MoMA, and I hope it will lead to gain even more interest.

Here in Japan, the difficult situation of a continuing recession and unstable political scene has been compounded by the nuclear accident that followed a devastating earthquake in March 2011. These issues in Japan have led to calls to rethink the country's nuclear policy and look once again at the meaning of the word "postwar" itself. In that sense, looking over "post-defeat art" will serve as an important link. So, the recently presented Experimental Ground 1950s, the second part of the exhibition titled Art Will Thrill You!: The Essence of Modern Japanese Art at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo was significant. I believe that we can reconsider what needs to be done for these contemporary matters by reexamining again and again the earnest message and philosophy towards reality, that underlie postwar art.

Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. (c) 2012 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

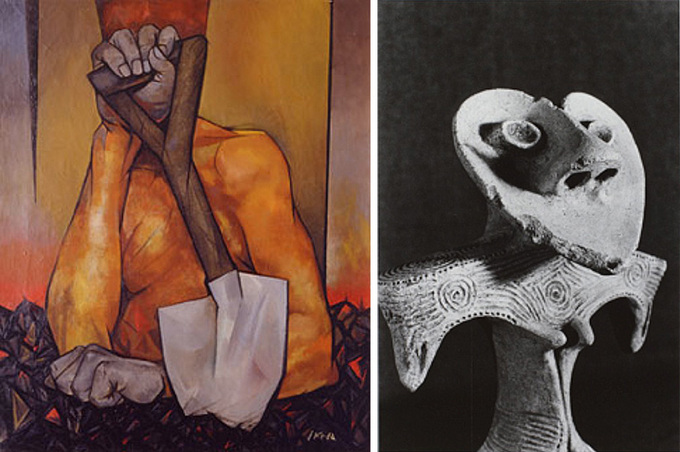

(Left) Ikeda Tatsuo Arm (Ude) 1953 Itabashi Art Museum, Tokyo

(Right) Okamoto Tarō Jōmon-period earthenware figurine 1956 Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki

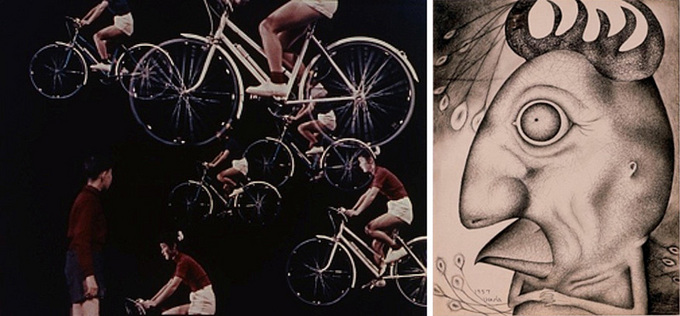

Ay-O Pastoral (Den'en) 1956 Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo

(Left) Matsumoto Toshio Bicycle in Dream (Ginrin) 1956 National Film Center, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo ©Tokuma Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd.

(Right) Ikeda Tatsuo Boss Bird (Bosu dori), from the series Chronicle of Birds and Beasts (Kinjūki) 1957 The Miyagi Museum of Art, Sendai

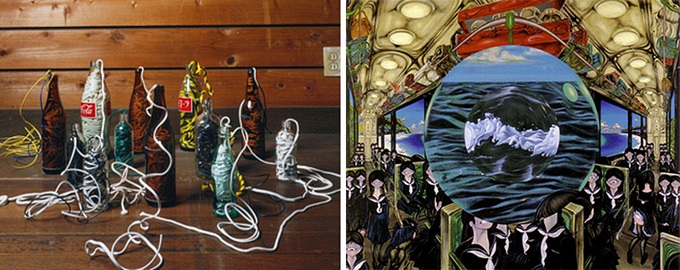

(Left) Takamatsu Jirō Strings in Bottles (Bin no himo) 1963 Private collection Photo: Tadasu Yamamoto

©The Estate of Jiro Takamatsu, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates

(Right) Nakamura Hiroshi Circular Train A (Telescope Train) (Enkan ressha A [Bōenkyō ressha]) 1968 Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo

Yuri Mitsuda

Art critic, curator of the Shoto Museum of Art. Mitsuda is a graduate of Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University, and is an expert on the history of modern and contemporary art and photography. Among her critical works are Words and Things: Jiro Takamatsu and Japanese Art 1961-72 (Daiwa Press, 2012), and Shashin, geijutsu to no kaimen ni: Shashin-shi 1910s-1970s (A history of photography from 1910s-1970s, (Seikyusha, 2006), for which she won the Photographic Society of Japan Award for Scholastic Achievement in 2007.

Keywords

- Design

- Photo

- Architecture

- Film

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- Music

- Politics

- Economics/Industry

- History

- International Exhibition

- Japan

- United States

- Museum of Modern Art New York

- Tokyo

- New York

- Taro Okamoto

- Noriyuki Haraguchi

- Ushio Shinohara

- Takahiko Iimura

- Lee Ufan

- Tatsuo Ikeda

- Katsuhiro Yamaguchi

- On Kawara

- Hiroshi Nakamura

- Natsuyuki Nakanishi

- Genpei Akasegawa

- Mokuma Kikuhata

- Ay-O

- Eiko Hosoe

- World War ll

- High economic growth

- Tokyo Summer Olympics

- EXPO'70

- Yoshie Yoshida

- Korean War

- Vietnam War

- Nagasaki

- Hiroshima

- Atomic bomb

- Okinawa

- Japan-U.S. Security Treaty

- Jasper Johns

- Yoshiaki Tono

- Fluxus

- Rauschenberg

- Woodblock printing movement

- Cho Yan Gyu

- Doryun Chong

- Chimei Hamada

- Josaku Maeda

- Metabolism

- Gutai art association

- Jiro Yoshihara

- Jikken Kobo

- Experimental Workshop

- Takiguchi Shuzo

- Yoko Ono

- CIE library

- Hi Red Center

- Jiro Takamatsu

- Shigeko Kubota

- Shusaku Arakawa

- Tetsumi Kudo

- Indépendent

- The Yomiuri Shimbun

- Walker Art Center

- Koichi Tateishi

- Katsuhiko Narita

- Kisho Kurokawa

- Kiyoshi Awazu

- Tadanori Yokoo

- Hiroshi Katsuragawa

- Toshio Matsumoto

- Zero Dimension

- VIVO

- Provoke

- Guggenheim Museum

- Atsuko Tanaka

- National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…