Inspirations from the Exhibition "How Did Architects Respond Immediately after 3/11--The Great East Japan Earthquake"

Taro Igarashi Architectural Critic

Housing Facility with Tower and Murals © Taro Igarashi Laboratory (Tohoku University)

Housing Facility with Tower and Murals © Taro Igarashi Laboratory (Tohoku University)

The possibility of Phase Zero

At the request of the Japan Foundation, I organized the global traveling exhibition "How Did Architects Respond Immediately After 3/11--The Great East Japan Earthquake." As the title suggests, the exhibition introduces the activities of architects following the earthquake and tsunami of unprecedented scale in northeastern Japan. I divided the projects featured in it into three phases: one, emergency responses, in which survivors evacuate to gymnasiums and other facilities; two, temporary housing; and three, reconstruction projects. Apart from these phases, I included a section on proposals submitted by foreign architects as examples of international exchange in an emergency situation. Let's take a look at the exhibition through each of the three phases.

The first phase, emergency responses, deals with measures taken for people whose houses were destroyed by the earthquake and tsunami, or who otherwise could not return to their own homes afterward. These people were accepted into evacuation shelters, which were originally school gymnasiums or classrooms, or in some cases cultural facilities. The number-one priority in this phase is speed. There is really not much architects can do, as it's too late to start pondering after the disaster has occurred. And yet in the world of architecture, various organizations were formed right away after 3/11 toward relief efforts. The cardboard shelters by the Toshihiko Suzuki Laboratory (Kogakuin University) and the curtains by textile designer Yoko Ando, for instance, provided simple solutions to partitioning the shelters, affording privacy and improving the evacuees' lives.

Elementary school gymnasiums are often the site of choice for evacuation shelters. But I find it interesting that famous contemporary architecture can also be converted into shelters. The Ofunato Civic Cultural Center and Library, aka Rias Hall, designed by Chiaki Arai, for instance, comprised compact interior spaces inspired by ria coast inlets, each of which served as a separate unit and created a pleasant living environment for evacuees. This and other cultural facilities raised the question as to their true value when they departed from their original purpose and were converted instantly into condominiums for evacuees. Perhaps they have made an example of the requirements of architecture in the future, the redundancy that may come in useful in an emergency situation.

Some activities can be conducted swiftly and meticulously only by local professional organizations. One example is the early-stage recovery support provided by the Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) Tohoku Chapter. While many architects from regions other than Tohoku rushed to the disaster-hit areas after late March, when traffic had resumed, local architects had the advantage of getting involved straightaway. The JIA's home consultation services were covered nonstop by local TV stations and other mass media starting right after the disaster. Even though more popular media like magazines might spotlight only the efforts of star architects based in Tokyo, we must not forget the contribution of these local players. In the exhibition, I have tried as much as possible to feature the activities of local architects.

In 2008, Ryo Yamazaki held a workshop titled Shinsai seikatsu + dezain (Evacuation Life + Design), which studied the challenges of evacuating to a gymnasium. The following year, he published Shinsai no tame ni dezain wa nani ga kano ka (What Design Can Do for a Disaster). In other words, his workshop envisioned what I call Phase One, emergency responses. But in the sense that he approached design from the step before a disaster occurs, he had predicted that efforts were necessary before my three phases--that is, a Phase Zero.

A proliferation of projects

The second phase, temporary housing, involves providing the people who were displaced and living in evacuation shelters with a large number of short-term living quarters. After 3/11, more than 50,000 of these facilities were constructed. With prefabricated houses, though, the key often lies in the production system, and again there is a limit to what architects can do after the disaster has occurred. That is, even if they come up with a good design, by then it would never make it to production in time. This time, what they did instead was prepare manuals for the temporary houses, recommend their placement, supplement them with attached facilities, and customize the living spaces. I should also note that because the damage was so extensive, and the supply of prefabricated houses fell short of demand, architects also played a role in the development of a variety of wooden temporary houses across the stricken areas. Kibo no sato: kizuna (Town of Hope: Neighborly Bonding) in Tono City, Iwate, and the Temporary Housing Facility with Tower and Murals in Minami-Soma City, Fukushima, are but two examples.

How Did Architects Respond Immediately After 3/11 introduces well over 50 projects. I might say it was one of the largest exhibitions of its kind held in March 2012, a year after the disaster, like "Making as Living: The Exhibition of The Great East Japan Earthquake Regeneration Support Action Project" at 3331 Arts Chiyoda in Tokyo, and the "1.17 / 3.11 Architecture for Tomorrow" exhibition in the Kansai region of western Japan. This is because rather than narrowing down the projects, I actually sought to emphasize their sheer number. The Great East Japan Earthquake was in fact larger in scale than the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, and I wanted to demonstrate that an overwhelming number of projects has emerged accordingly.

In part, this owes to the extent of the damaged areas and to the fact that these areas were close to Tokyo, where there are plenty of architects and educational institutions. Also, architects like Shigeru Ban and Tadashi Saito were quick to act, as this was not their first disaster but their second, following relief activities either in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake or abroad. Foreign architects submitted some notable proposals, too. A Belgian university launched the Ishinomaki Architecture Workshop (IAW) to help reconstruct the damaged city in Miyagi, and the African Republic of Cape Verde offered to accept a whole community of fishers in a Japanese Village Project. I have organized the exhibition so as to communicate this movement broadly to overseas audiences.

The exhibition kicked off on March 2, 2012, at Tohoku University in the stricken city of Sendai, Miyagi. The venue was a temporary annex constructed to replace the Laboratory Building of Architecture, which was badly damaged by the earthquake--and which was part of the exhibition. That is to say, the venue itself was a 1:1 scale exhibit. In addition to panels, the displays consist of maps that show the location of each project, videos and drawings, architectural models, and actual cardboard furniture and huts. At the entrance there is a raised relief map of the devastated Onagawa Town and Kesennuma City in Miyagi. This serves as a visual representation of the ria coast, which has become familiar to the Japanese but may not ring a bell with foreigners.

Exhibition at temporary annex building at Tohoku University, Sendai City, Miyagi

Exhibition at temporary annex building at Tohoku University, Sendai City, Miyagi

I arranged for the production of two sets of exhibit: one for the Sendai venue and the other for the exhibition starting March 6 on the first and basement floors of the Japan Cultural Institute in Paris. For two years afterward, the two sets are slated to travel the world--countries like Russia, Armenia, and South Korea, and cities like Cologne, Rome, and Beijing. This world tour as well as other events, like the exhibition "RESET 11.03.11#New Paradigms" on contemporary Japanese architecture in Barcelona, and the symposium "Ville et architecture après le 11 mars--Comment les architectes régénèrent-ils le local? (Architecture and Cities After 3/11--How Will Architects Regenerate the Region?)" in Paris, testify to the great interest in post-3/11 Japanese architecture.

The phase that tests the capacity of architects

I selected the projects featured in the exhibition in November 2011. As such, many examples of the second phase, temporary housing, had already become a reality, whereas most examples of the third phase, reconstruction projects, were still in the planning stage. One popular concept for this third stage was to move entire towns to high ground. But doing this across the board with every single devastated community does not quite solve the problem, as each community is different. The Yuriage Renaissance Project launched by Shoichi Haryu et al. thus seeks to create safe, secure living environments without changing geographical features or moving groups of people, but by restoring towns to their original, familiar landscape. Projects like this cannot be planned in the first or second stages, as they take time. But the third stage, reconstruction projects--this is the phase where the capacity of architects, their "space literacy" or ability to read between the lines of places, comes into full play.

The 3/11 disaster inspired many ideas in architects, from Home-for-All by Toyo Ito et al. slated for display in the Japan Pavilion of the 13th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice Biennale (starting August 2012), to the national land planning project by Ryuji Fujimura, to the ArchiAid network of architects to support reconstruction at the micro level. A series of workshops conducted by this ArchiAid at the Oshika Peninsula in Miyagi attracted members from 15 university laboratories to research and propose solutions for the diverse local features of fishing villages. ArchiAid focuses its attention even on small communities that might be neglected by consultants and general contractors, and offers ideas for reconstruction.

Japan will never be rid of earthquakes and tsunami. These disasters are bound to keep coming at regular intervals. And this is why it's important for reconstruction projects to embrace past experiences. Architects should not only document their memories on paper and in digital archives, but also, as in the projects by Katsuhiro Miyamoto and by Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and his lab at the Tokyo Institute of Technology and through the preservation of architectural relics, incorporate their memories at the physical level into developing new communities. Many such projects will become a reality only in and after 2012. A forerunner of these projects is the competition in autumn 2011 and early 2012 of proposals to build nurseries and schools in the town of Shichigahama, Miyagi, with support from ArchiAid. This is featured as the final project in Phase Three of the exhibition. Speaking of the exhibition, I included the word immediately in title so that in the course of its two-year tour the audiences wouldn't think the projects were out of date. That is, the title serves as a reminder that the aim of the exhibition is to introduce what was possible in the six months or so immediately following 3/11.

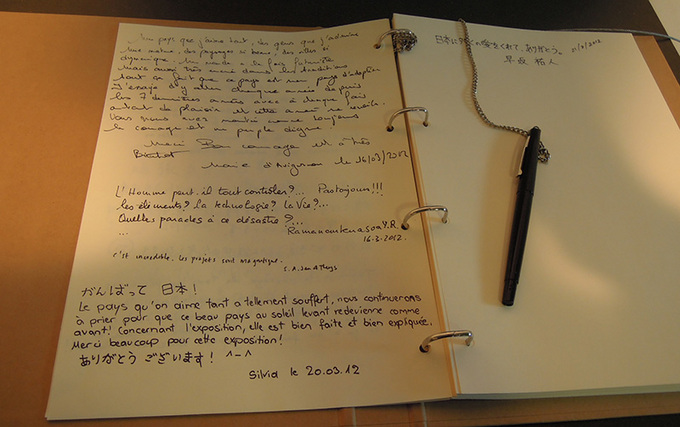

On my visit to the exhibition in Paris to deliver a lecture, I leafed through the guest book and was struck by the messages of encouragement for Japan and admiration for the number of projects that had emerged right after the disaster. In a different program organized by the Japan Foundation, in March I delivered a lecture on post-3/11 architecture in Vietnam, which is pressing ahead with nuclear power generation and where the audience's interest lay in its safety. Whereas earthquakes and tsunami are common in Japan, they do not happen in all regions of the world. France and Vietnam have no worries. And yet every country has its own unique natural disasters. France and Vietnam, for instance, do have floods and hurricanes. The nuclear accident in Japan has drawn much attention worldwide, and in fact many of the questions I received in both countries concerned this theme. I must admit it is difficult for architecture to respond to or propose solutions for a nuclear accident. But I believe the exhibition will deliver the message that Japanese architects are standing up to the recent disaster, and that it will encourage architects of other countries to think about the steps to take if their region is hit by a disaster--solid steps that start with Phase Zero.

Guest book from the exhibition in Paris

Guest book from the exhibition in Paris

Exhibition "How Did Architects Respond Immediately After 3/11--The Great East Japan Earthquake" https://www.jpf.go.jp/e/project/culture/exhibit/traveling/architecture_311.html http://www.mcjp.fr/francais/conferences-6/ville-et-architecture-apres-le-11-311/ville-et-architecture-apres-le-11 http://www.jpf.go.jp/overcoming/en/exhibition.html http://www.jpf.or.kr/column/news/200910/20091015000001.html

Taro Igarashi

Architectural historian and critic born 1967 in Paris, France. Igarashi completed a master's course at the University of Tokyo Graduate School in 1992. He is currently a professor at the Tohoku University School of Engineering. He serves as artistic director for Aichi Triennale 2013, and was the Japan Pavilion Exhibit Commissioner for the 11th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice Biennale (2008). Publications include Gendai Nihon kenchikuka retsuden (The Lives of Contemporary Japanese Architects; Kawade Shobo Shinsha Publishers) and Hisaichi wo arukinagara kangaeta koto (What I Thought About While Walking the Disaster-stricken Areas; Misuzu Shobo).

Taro Igarashi

Architectural historian and critic born 1967 in Paris, France. Igarashi completed a master's course at the University of Tokyo Graduate School in 1992. He is currently a professor at the Tohoku University School of Engineering. He serves as artistic director for Aichi Triennale 2013, and was the Japan Pavilion Exhibit Commissioner for the 11th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice Biennale (2008). Publications include Gendai Nihon kenchikuka retsuden (The Lives of Contemporary Japanese Architects; Kawade Shobo Shinsha Publishers) and Hisaichi wo arukinagara kangaeta koto (What I Thought About While Walking the Disaster-stricken Areas; Misuzu Shobo).

Related Events

Keywords

- Architecture

- Social Securities/Social Welfare

- Natural Environment

- International Exhibition

- Republic of Korea

- China

- Japan

- Viet Nam

- Italy

- Spain

- Germany

- France

- Armenia

- Russia

- Cape Verde

- Taro Igarashi

- 3.11

- Great East Japan Earthquake

- Earthquake

- Tsunami

- Temporary housing

- Reconstruction

- Kogakuin University

- Toshihiko Suzuki

- Yoko Ando

- Chiaki Arai

- Ofunato City

- Japan Institute of Architects

- JIA

- Ryo Yamazaki

- Tono City

- Minami-Soma City

- 3331 Arts Chiyoda

- Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake

- Shigeru Ban

- Tadashi Saito

- Ishinomaki Architecture Workshop

- IAW

- Republic of Cape Verde

- Sendai

- Tohoku University

- Onagawa

- Kesennuma

- The Japan Cultural Institute in Paris

- Shoichi Haryu

- Yuriage Renaissance Project

- Venice Biennale

- Toyo Ito

- Home-for-All

- Ryuji Fujimura

- ArchiAid

- Katsuhiro Miyamoto

- Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

- Cologne

- Rome

- Beijing

- Barcelona

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…