New Trends in Japanese Cuisine Blossoming Overseas

Yumiko Sakuma

Let's take New York City as an example: before the unprecedented boom in Japanese cuisine sparked in 2004 by the launch of large upscale Japanese restaurants such as MEGU, Matsuri and EN Japanese Brasserie, about 85% of Japanese-style restaurants were sushi restaurants run by non-Japanese. Fast forward seven years, and today Japanese food is becoming even more popular overseas, with a constantly expanding array of choices ranging from soba and ramen noodles to deep-fried tempura, grilled yakiniku meat, yakitori (char-broiled chicken), kaiseki-ryori (traditional multi-course meal) and more. We asked professionals in the food business about the changes in Japanese cuisine abroad.

The first person we spoke to was Colman Andrews, a food critic and editorial director for the online food magazine The Daily Meal. He has never visited Japan, but the New York-based critic has sampled Japanese cuisine in various cities in the U.S. and Europe.

"The first sushi restaurant in New York City opened in the 1950s. The majority of Americans still equate Japanese cuisine with sushi, which has been widely accepted as a healthy, low-calorie food. But the variety of Japanese cuisine available to diners with discerning palates is growing."

"The first sushi restaurant in New York City opened in the 1950s. The majority of Americans still equate Japanese cuisine with sushi, which has been widely accepted as a healthy, low-calorie food. But the variety of Japanese cuisine available to diners with discerning palates is growing."

As mentioned earlier, 2004 saw the opening of a succession of large restaurants run by Japanese. Each offered dishes other than sushi on the menu, letting the public know that Japanese cuisine is not synonymous with sushi. Since then, a number of small, highly specialized restaurants serving yakitori, ramen, soba, kaiseki, robata-yaki (food cooked in an open hearth) or shojin-rori (Buddhist vegetarian cuisine) have opened, creating something of a washoku (Japanese cuisine) boom.

Andrews made an interesting point about the price range of Japanese cuisine. "It's normal to see packages of California rolls and other sushi rolls at supermarkets and delicatessens. But at the same time, in larger cities in the U.S. and Europe, Japanese restaurants are replacing the French as the most expensive restaurants in town."

In the 1990s, sushi spread from the U.S. across the world, riding the wave of the health-food boom. He noted that in the 2000s, Japanese cuisine came to be regarded as premium dining after a number of "authentic Japanese restaurants" were opened by Japanese chefs.

"What's interesting is that an increasing number of diners are willing to pay more for Japanese food, where fresh ingredients and chefs' finesse is vital, than for French cuisine that requires a long and complex cooking process."

EN Japanese Brasserie is one of the "authentic Japanese restaurants" that Andrews frequents in New York City. Owner Reika Alexander was prompted to open a restaurant when she visited New York in 2000, where she was shocked to see how fusion cuisine incorporating the essence of Japanese food went by the name "Japanese cuisine." She decided to open a restaurant that would be a sister operation to the chain run by her brother in Tokyo.

"At that time, there were no restaurants serving proper Japanese food to Americans. We want to give customers the feeling of dining out in Tokyo."

From the design of the restaurant to the menu, Alexander carefully avoided "catering to Americans." They made fresh tofu six times a night, with a note on the menu indicating what time it would be ready. In 2008 she was invited to appear on Martha Stewart's television show and demonstrated how to make fresh tofu.

"When we first opened, we were asked, 'Do you have spicy tuna roll?' or even asked for hot sake in the middle of hot summer. Now, more guests ask to be seated at the counter seats, which they used to avoid. I think the people's 'IQ level' on Japanese cuisine is increasing."

One of the reasons behind this is the rise in the number of people providing introductions to Japanese food culture, and an increase in resources such as recipe books. Harris Salat, who writes the blog The Japanese Food Report, has been offering guidance to Japanese food culture through magazines, books and the Internet. Salat, who worked as a cook in his 20s, later went into journalism but was inspired by the food culture when he visited Japan to learn about pottery. While writing about Japanese food for The New York Times and various gourmet magazines, he trained in the kitchen for about a year under Tadashi Ono, chef of Matsuri restaurant. Salat's blog, which he began writing to jot down all the things he learned about Japanese food, including recipes, receives about half a million hits a year.

"A U.S. Navy captain sent me an email that said, 'I really like your receipe.' It's not only urban gourmets who are interested in Japanese food."

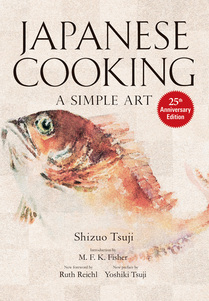

Asked what aspect of the Japanese cooking method appeals to Westerners, Salat cited Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, a cookbook published by Shizuo Tsuji in 1980 that is still widely read.

Asked what aspect of the Japanese cooking method appeals to Westerners, Salat cited Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, a cookbook published by Shizuo Tsuji in 1980 that is still widely read.

"Western-style cooking and Japanese cuisine have totally different approaches. Whereas Western cuisine creates taste by adding layers of flavor, Japanese cuisine takes a simple approach, using seasonings such as miso, mirin (sweet cooking sake) and soy sauce that already incorporate "umami" (savory taste), and finding a perfect point where they blend. This is why the cuisine appeals to a large number of people. Of course, people must train to acquire this simple approach."

When asked to comment on current trends in Japanese cuisine, Colman Andrews also pointed out the impact of the Japanese cuisine boom, referring to its influence on the styles of chefs of other cuisines.

"It's no longer unusual to use the more delicate yuzu juice instead of lemon in a sauce or to use soy sauce as a hidden flavor. An increasing number of Italian restaurants have a list of crudo, or raw fish, on their menu. Italian chef Moreno Cedroni was inspired by sushi and developed an Italian-style sushi he calls "Susci." Although raw fish is used, he added Italian twists such as cooking the rice into risotto. As a result of these developments, chefs around the world are now able to obtain much fresher fish. The Japanese cuisine's profound impact on the global food culture is unlimited."

David Bouley is one of the renowned chefs who were significantly influenced by Japanese cuisine. His encounter with Japanese food came in the 1980s when he began visiting a sushi restaurant that was open late at night, after his own place closed.

"Although many Western chefs incorporated wasabi and ponzu sauce in their recipes at that time, most of us had no understanding of the cultural background."

"Although many Western chefs incorporated wasabi and ponzu sauce in their recipes at that time, most of us had no understanding of the cultural background."

His visit to Japan in the late 1990s at the invitation of Yoshiki Tsuji of the Tsuji Culinary Institute Group led him to study Japanese cooking methods, history and philosophy.

"Japanese chefs know how to clean and fillet a fish without reducing its freshness. It's not about how good a certain seasoning is or how good the recipe is but rather, the strength of Japanese cuisine lies in the craftsmanship that enhances the essence of the ingredients and the surrounding food culture."

In April 2011, Bouley opened a kaiseki restaurant called Brushstroke in collaboration with Tsuji.

"I wanted to open a restaurant for those who like sushi and sashimi (raw fish) and who may know something about Japanese grilling methods, yet are not familiar with the refined expression of kaiseki-ryori."

Bouley has another reason for opening a kaiseki restaurant, namely the health aspect of the ingredients used. "I once prepared a dish using kudzu starch for a diabetic friend and learned that the friend's blood sugar level did not rise. About a quarter of the child population in the U.S. is diabetic. We have a lot to learn from Japanese cuisine."

Nowadays Alexander of EN Brasserie is using the restaurant as a base for a broader range of initiatives to introduce the culture of Japanese cuisine overseas, expanding the lineup of shochu distilled spirits for guests who are acquainted with sake, and holding cooking classes. At frequently held events, local specialties from Japan are presented by Japanese food experts who fly in for the occasion. Bouley has named one of his dining rooms "Chef's Pass," where producers of ingredients and seasonings from Japan and other countries describe the production process and healthful effects of various foods to diners via Skype. Salat is preparing to open his own restaurant while writing a book on Japanese cuisine.

"There's still a wide gap between Japanese cuisine and what the world knows about it. How can we bridge this gap?--that's our challenge."

David Bouley

David Bouley

Born in Connecticut. After stints at restaurants across the U.S., he worked under Paul Bocuse in France. He returned to the U.S. and worked at leading restaurants including Le Cirque before opening his own restaurant Bouley in 1987. While his restaurant was closed temporarily in the late 1990s, he met Yoshiki Tsuji of the Tsuji Culinary Institute Group and visited Japan where he became acquainted with Japanese cooking methods. He has made repeated visits to Japan and is studying the art and philosophy of Japanese cuisine. http://davidbouley.com/

Colman Andrews

Colman Andrews

Born in California. After working as an editor for a number of lifestyle magazines, he began freelancing, writing articles on food and wine for Food & Wine, Bon Appetit and many other magazines. In 1994, he launched the food magazine Saveur and moved to New York City. Currently he works as the editorial director of thedailymeal.com. He has written a number of recipe books and other books including Ferran: The Inside Story of El Bulli and the Man Who Reinvented Food, about the renowned Spanish chef Ferran Adrià. http://www.thedailymeal.com/

Reika Alexander

Reika Alexander

After returning from studies in London, she was asked in 2000 to check out the restaurant business in New York City for her elder brother, who operates a restaurant chain in Tokyo. She eventually decided to open a restaurant there serving authentic Japanese cuisine. In 2004, she opened EN Japanese Brasserie in Tribeca. In 2008, she appeared on Martha Stewart's talk show. She now runs the restaurant with her husband Jesse Alexander. Immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake hit Japan in March, she co-organized a charity event with Stewart. http://enjb.com/

Harris Salat

Harris Salat

Born in New York. After working as a cook and at other food-related jobs during his 20s, he turned to freelance journalism in 1991. His interest in pottery brought him to Hagi, Japan. The visit sparked a passion for Japanese food culture and he began writing articles on the subject for newspapers and magazines. At the same time, he spent about a year learning the art of Japanese cooking in the kitchen of Matsuri, Chef Tadashi Ono's restaurant in New York City. Salat co-wrote The Japanese Grill with Ono. http://www.japanesefoodreport.com/

Yumiko Sakuma

Sakuma is a New York-based writer. Born in 1973, she grew up in Tokyo. After graduating from Keio University, she earned a master's degree at Yale University. She has lived in New York since 1998. After jobs in publishing and news services, she started working independently in 2003 and now writes extensively on culture for various media. http://www.yumikosakuma.com

Photos of David Bouley and Colman Andrews by Shiori Kawasaki

Japan Foundation program to introduce Japanese cuisine overseas

Shojin-ryori from the Tohoku region and the Three Mountains of Dewa

Shojin-ryori from the Tohoku region and the Three Mountains of Dewa

Mountain priests wearing traditional costume marched in Paris while blowing on trumpet shells. They expressed gratitude for the support Japan has received from around the world, and offered prayers for the recovery of the areas affected by the earthquake.

Traditional Ryukyu cuisine from Okinawa presented in Paris, Sweden and Germany through lectures and demonstration

Traditional Ryukyu cuisine from Okinawa presented in Paris, Sweden and Germany through lectures and demonstration

The art of Japanese cooking demonstrated in Vietnam, Laos and Brunei, as well as Romania and Ukraine

The art of Japanese cooking demonstrated in Vietnam, Laos and Brunei, as well as Romania and Ukraine

Keywords

- Food Culture

- Cultural Diversity

- Japanese Studies

- Japan

- United States

- Japanese food

- Japanese cuisine

- Washoku

- New York

- MEGU

- Matsuri

- En Japanese Brasserie

- sushi

- Daily Meal

- Colman Andrews

- Reika Alexander

- Martha Stewart

- Harris Salat

- Tadashi Ono

- Shizuo Tsuji

- Moreno Cedroni

- David Bouley

- Yoshiki Tsuji

- Brushstroke

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…