Erasing Borderlines with Music--The Tambuco Percussion Ensemble in Japan

Mari Ohashi

Music journalist

The four-member Tambuco Percussion Ensemble from Mexico has received the 2011 Japan Foundation Award for their major contribution to promoting the understanding of Japanese arts and culture around the world. The significance of this accomplishment is evident from the list of previous winners of the award, including musicians such as Seiji Ozawa, Yuriko Kuronuma, Toru Takemitsu, Midori, Ikuma Dan, Naoyuki Miura, and Toshiko Akiyoshi, as well as Wolfgang Sawallisch, Honorary Conductor Laureate of the NHK Symphony Orchestra, who was the only foreign-born winner of the prize since its founding in 1973.

Tambuco and Japan

Violinist Yuriko Kuronuma, who resides in Mexico and knows Tambuco well, spoke to us about their music at the award ceremony.

"Without any special commission, the group has been performing Japanese modern music on their own initiative at major concert halls around the world. Their superb artistry has added another dimension to the music, and has even helped us Japanese rediscover Japan. They are our musical ambassadors, even though they are not Japanese." (excerpt)

Although not yet well known in Japan, Tambuco is in fact one of the leading percussion ensembles in the world.

Their mission, they say, is to explore new horizons for percussion music, to share their performances with more and more people, and to make the percussion works of Latin American composers more widely known.

Guided by these three goals above, the group formed in 1993, and has countless percussion pieces in its repertoire. They are constantly commissioning new pieces from composers, in addition to which they receive pieces from musicians who voluntarily create works especially for Tambuco. New compositions arrive at the rate of about one per week. If you look at their repertoire, you will be amazed at its size, the variety of genres, and the internationality of the composers. Just looking through the list thrilled me, as a hitherto unknown world seemed to unfold before my eyes.

Tambuco has worked with many Japanese musicians. They have performed Mexican or Latin American premieres for sixteen pieces by ten different Japanese composers, and have played with seven Japanese artists, including specialists in both Japanese and Western music. One of the nine CDs that they have released features Japanese percussion music with Akira Nishimura, Jo Kondo, Takehito Shimazu, Toru Takemitsu, and Keiko Abe. (For details, please see Tambuco's Discography on their website.)

Although Tambuco has connections with music from all over the world, they are especially interested in Japanese music. Artistic director and member of the ensemble Ricardo Gallardo gave us his story.

Although Tambuco has connections with music from all over the world, they are especially interested in Japanese music. Artistic director and member of the ensemble Ricardo Gallardo gave us his story.

"I've felt close to Japan ever since I was a kid. Japanese cartoons like Ultraman were shown on Mexican TV, and my sister went to the YAMAHA Music School. But studying under Keiko Abe, a world class percussionist, brought me even closer. Akira Kurosawa's movie Dodes'ka-den was a big influence. I loved the music by Toru Takemitsu, and the title of the movie with its vibrating percussion-like sound. Japan is a mix of old and new, and that balance gives it a unique charm. And even the old things are amazingly modern. For example, Japanese traditional instruments have hardly changed at all over the years, and are still played today."

Ricardo is interested in what young people in Japan are thinking in this age of globalization, and wants to see how they will express the balance between the old and new in their music. He said he was eager to collaborate with young Japanese composers. At the concert held on October 7, 2011 at Toppan Hall in Tokyo to commemorate Tambuco's winning the Japan Foundation Award, the audience was instantly mesmerized by their music. Words cannot express the spellbinding power of the performance, but I will try to convey the feeling of the event, while referring readers to actual footage of the concert which can be seen on YouTube.

The Japan Foundation Awards Commemorative Concert by the Tambuco Percussion Ensemble

The sold-out concert started at 7:30 p.m. on October 7, 2011 at Toppan Hall. The first half of the program consisted mainly of works written for Tambuco by Central and South American composers.

A warm round of applause greeted the four members of the group. They took their places on the left-hand side of the stage where four marimbas were placed. The show started off with a piece titled Prismas, written by the Columbian composer Claudia Calderson in 1999. This lively and energetic piece is written in the style of Afro-Colombian dance music from the Pacific coast of South America. I felt as though I were looking through a kaleidoscope of music, as each performer kept his own melody and rhythm, while the sounds wove around each other, expanding and shrinking on top of the two chords. Being surrounded by the endless repetition of the soothing sounds had a hypnotic effect. The subtle inconsistency of the rhythm and the occasional clash of dissonance added spice. The Tambuco marimba quartet seemed to dance together like a single organism. The impeccable technique and ensemble performance won the hearts of the audience from the first number.

Next was a piece called the Rhythmic Structure of the Wind I (2009) by Raúl Tudón, a member of the ensemble who is also a composer. The four moved to a table placed at the opposite end of the stage, and stood in pairs facing each other. An assortment of instruments that had been collected or made by the group formed a beautiful collage on the table, while more instruments stood next to the table or on the floor. Alfredo Bringas, the artisan member of the group, has a talent for making instruments. The display included a brand-new instrument he had created that day by piercing a small hole at the bottom of an instant noodle container and passing a string through the hole to make a frictional sound. (To me, it sounded like a dragon sighing.)

What if we could hear the wind as closely as we can see things through a microscope? That idea was the inspiration for this piece. The ensemble improvised and wove a fabric of sound while listening to computer music that had been previously laid down on CD. The music seemed to reflect the introspective character of the composer. It would have been even more interesting if we could have seen which instrument each player selected, maybe on a large screen, but that might be asking too much.

The third number was the 2005 version of Metro Chabacano composed by Javier Alvarez in 1991. The music was first performed in 1991 at Metro Chabacano, a subway station in Mexico City, at the opening of an installation by Marcos Limenese, a renowned Mexican contemporary artist. It was originally composed for string quartets and presented to the Latin American String Quartet, but was arranged as a piece for marimbas in 2005 for Tambuco. This short piece consists of only one movement with a repeated eight-note pattern that gives it a lively sound. The composition of the piece is actually quite complicated, with rhythm and melody woven in between the regular repetition of notes, resulting in complex accents that keep the listener's attention. It evokes the sort of urban scene found anywhere in the world, where busy people go to and fro. Tambuco's sharp, clear-cut rhythms and perfectly united ensemble playing brought out the full beauty of the work and left the audience enchanted.

The ensemble came to center stage for the first time and stood in a line to play the fourth number, Stone, Song, Stone Dance, composed in 2000 by British born Paul Barker, the only European composer on the program. With a stone in each hand (although I'm not sure stone is the appropriate word), three players stood with their hands at chest level, striking or rubbing the stones together, and swinging their arms up over their heads in wide arcs. While they made the stones sing, the fourth player accompanied the music with bells.

The next instant, the meditative, mystical atmosphere was transformed when all four members simultaneously broke into a furious rhythm, "the stone dance." Solo performances were interwoven into the flawless ensemble performance, displaying Tambuco's unbelievable precision, masterly technique, and flashes of humor (at one point, they even played Mozart on the stones!) Who could have imagined that such subtle and diverse sound could be produced from stones, and that it could even become music? The audience was astounded and delighted to have seen and heard something truly original.

The first half of the program ended, of course, with Organika, a marimba quartet piece composed in 2008 by Mara Granillo. It is part of a large-scale projected series on the theme of birth, growth, reproduction, multiplication, decline, and death of organisms, that is being created for Tambuco. They played the introduction to the work, Brotes, which uses a contrapuntal style to depict a cell filling up with energy, starting to divide, and then steadily multiplying, in the process of ceaseless growth and division through which complex organisms are created. Only a group like Tambuco, all four of whom are masters of the marimba, could handle a work this musically challenging.

After intermission, the audience, still exhilarated by the amazing discoveries of the first half, returned to their seats and waited for the program to resume. The second half included three pieces, two by Japanese composers, as well as Tambuco's signature number.

Nanae Yoshimura on the 20-string koto and Kifu Mitsuhashi on the shakuhachi (bamboo flute) appeared at center stage. Behind them, the ensemble stood in a semi-circle with their percussion instruments, conga, bongo, and bass drum. The first number was Sound Sound IV for Shakuhachi, 20-stringed Koto and Percussions composed by Masataka Matsuo. The piece was commissioned by the 2005 Festival Internacional Cervantino for Tambuco. Six years later, this concert was the first time it had been played by the original members in Japan.

Established in 1972, the Festival Internacional Cervantino is an international arts festival held in and around the historical city of Guanajuato, a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. Exhibitions of every form of art, including music, theater, dance, fine arts, film, and literature, attract thousands of artists and hundreds of thousands of visitors from all over the world, making this one of the world's leading festivals.

The composer Matsuo, who attended the Cervantino festival in 1993 for the International Society for Contemporary Music, told us that he had seen Tambuco perform there more than ten years before he was asked to write for them in 2005. Their versatile performance at the percussion instruments exhibition during the festival made a deep impression on him. He was convinced that Tambuco could play anything he wanted to write, and so was able to compose freely with no hesitation. Sound Sound IV is an exquisite piece with delightful harmonies, in which Japanese and percussion instruments resonate in a beautiful balance. The long climax was played by an ensemble of shakuhachi and percussion, with the 20-string koto taking the lead. The tetrachord motif was folded in here and there by the percussionists, who effectively used the technique of adding tension to the drum face with their elbows to intensify the tetrachords. It was interesting to hear that this technique was Tambuco's idea, not part of Matsuo's directions. Their creativity allows them to grasp the composer's intention, and to come up with innovative ways to express it while searching for new sounds. Many composers who have contributed works to the group comment on the originality of Tambuco's interpretations, both in the selection of instruments, and in the method of playing, so that even the writers themselves are surprised (and pleased.)

Once again, the members of Tambuco stood in a line at center stage. The piece was Hematofonía, written in 2008 by the Mexican composer Héctor Infanzón. According to artistic director Ricardo Gallardo, the title means "a tune that will give you bruises." They clap their hands and fingers, hit their knees, strike their chests and slap their cheeks; every part of their body becomes an instrument. Sometimes they almost knocked themselves down with the force of the blows. It certainly looked like they would be covered in bruises. It was a performance that only Tambuco could come up with.

In the middle of the piece, the members took turns improvising solos. These performances showed off the keen sense of humor and the unique personalities of the four players: sharp and mysterious Raúl, steady, unshakable Alfredo, the sincere perfectionist Miguel, and Ricardo, a superb leader who even conducted the audience's applause. He had them clap their fingers to produce a brilliant portrait in sound of a rainy day, moving from drizzle to downpour, then back to drizzle, interspersed with birdsong in a blue sky. It was a gorgeous moment, with the audience captivated by the magic of Tambuco.

Marimba Spiritual, composed by Minoru Miki in 1984, was the next number. Like many other percussionists, Tambuco selected this piece to end the concert. This famous work has been played more than ten thousand times throughout the world, and is a 20th century classic that every percussionist wants to perform at least once. This was the only piece in the program that was not written for Tambuco. Miki composed this music for Keiko Abe, a master marimba player who was also Ricardo's teacher. The first part is like a prayer, a requiem, and the second part, based on the lively music of Chichibu-yatai-bayasi (instrumental music played during the Chichibu-matsuri festival), portray the awakening of the spirit. The superb artistry of Tambuco drew gasps of amazement from the audience. Miguel, the youngest in the group, played the marimba solo, and the other three accompanied him. This is also considered a very "open" composition, in which the style of the performance and the instruments to be used are left for the artists to decide; the composer only specified that they use wood, metal and drum percussion instruments. The Tambuco version had an intriguing pre-Hispanic or Afro-Caribbean sound, which seemed to surround the stage like a halo.

They played two numbers as an encore. The first was ¿Sábe cómo e'?("Did you understand?") by the Mexican composer Leopoldo Novoa, played on a type of guiro called a guacharaca. This broomstick-like instrument, about the size of a child's violin, has ridges carved into the outer surface and is played by scraping it with a stick. On the stage, the players looked as if they were violinists in a string quartet. Although the piece is a comical parody, the music itself explores a world of delicate sound. This number was also performed at the presentation ceremony for the Japan Foundation Awards.

The second encore number was Tambuco por Brelias, a flamenco dance music arranged by Miguel González. The instrument was called a cajón, a wooden box with a hole on the side. Each player sat astride one of these boxes, pounding it wildly, bringing the show to a festive finale.

Tambuco's Beginnings

Many people probably think that the name "Tambuco" has some connection with the word tambor, meaning "drum," but that is not the case.

"There were several reasons for naming the group 'Tambuco.' It was actually the title of a piece for six percussionists written in 1964 by the great composer Carlos Chávez (1899-1978), one of the top Mexican musicians of 20th century. Chávez left numerous works of great value to the history of percussion music, and we took the name to show our respect for him. The word itself has no meaning, and we do not know why the composer chose it as his title--probably because the word has a clear and crisp sound, like percussion instruments: tam-bu-co. We also liked the sound of the word ourselves, and the fact that it is easy to pronounce in any language."

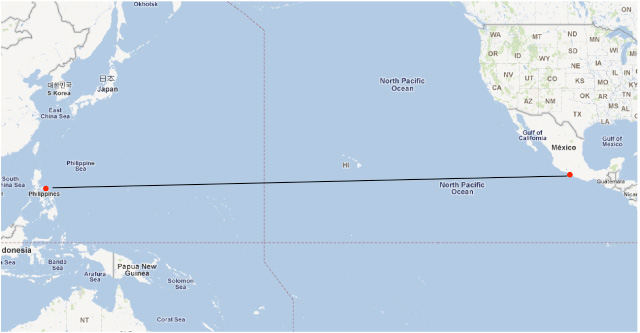

I did some research on the word "tambuco", and found that there was a seaside town of that name near Acapulco in Mexico. Furthermore, the island of Julita in the Philippines was formerly known as Tambuco. Both countries were Spanish colonies so there may have been a regular trade route connecting the two towns. Perhaps the town of Tambuco in Mexico was the destination for merchant ships from the other Tambuco, and came to be known by the same name. I also found out recently that the word can mean "platform" or "beginning."

As you can see, the name is certainly appropriate for a music group who consider performance as a kind of exchange with the audience, and who are always setting out towards new horizons of percussion music.

They said to me, "Now that Tambuco has performed in Japan, we are a Japanese ensemble. Music can erase national borders and reconnect people. What happens here will be answered there. Music shows people in the real world a way to bond together."

What can music do?

At the presentation ceremony for the Japan Foundation Awards, a commemorative symposium titled "Teachings of the Japanese Milieu--From the Rice Fields of Hokkaido to the Theories of Evolution" was held prior to the concert, with prizewinners in the Japanese Studies and Intellectual Exchange Division as panelists. After the symposium, I asked Ricardo, who was also in the audience, how music can help revitalize the areas devastated by the earthquake and tsunami in March.

"There is a piece called Síppal, dobbal, nádihegedűvel or flute, drum, fiddle, by the Hungarian composer György Ligeti (1923-2006). It's a collection of seven songs made by setting to music short poems written by Sándor Veress (1913-1989), a very popular poet in Hungary. The pieces were written for a mezzo-soprano and four percussionists. The poems are sometimes fable-like, and sometimes made up of nonsense words that are merely there to keep the rhythm. So I found it hard to see a connection between the words and the title. We invited the very talented singer Katalin Karolyi, for whom Ligeti had written the collection, to premiere the songs with us in Mexico, and at that time, she told us about the story hidden in the title.

"A stork seriously injured in war is enveloped in a plaster cast. The stork tells a concerned friend not to worry, that a flute, a drum, and a fiddle will heal his wounds."

Up until then, Ligeti hadn't written music for percussion instruments, but when he finally did, he composed a true masterpiece. The flute, drum, and fiddle are music. Music and art, that is, culture, heal society's wounds. People experience war or natural disasters, and they suffer spiritually. So we need music and art to heal them. That is my answer to your question. I will certainly play this collection of songs when I visit Japan again."

Ricardo added that, in the 21st century, it is not enough for musicians to be simply good at making music. They must also be fully aware that they are members of society. Musicians must prove to people that music is strong and alive, because as long as there is music, humanity will survive.

The Tambuco concert on the Gendai no ongaku (Contemporary Music) program on NHK FM radio:

Jan. 8, 2012 (Sun) 18:00 - 18:50

Jan. 15, 2012 (Sun) 18:00 - 18:50

Mari Ohashi (Music journalist, subtitle translator)

Mari Ohashi (Music journalist, subtitle translator)

Graduated from Department of Musicology, Tokyo University of the Arts.

Developed programs for TOKYO FM radio, including Sekai no ongaku wo anatani (The Music of the World to You), Trans World Music Ways, and The Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra Opera Concertante Series (produced by Kazushi Ono). She has translated subtitles for The Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra Opera Concertante Series, music documentaries (ARTE and others), Bernstein's Candide (performance at Hyogo PAC), From the House of the Dead by Leos Janacek (NHK BS), and many others. She has contributed CD reviews to columns in The Asahi Shimbun (Kiku (Listen)) and The Nikkei; and stage reviews to Musicanova magazine published by Ongakunotomo Sha. In 2004, she studied development of music education and programming at the European Network for Opera and Dance Education (RESEO), sponsored by the overseas study program of Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs. She has organized premiere performances in Japan for Accordone, Triology and Le Poème Harmonique.

Related Events

Keywords

- Traditional Arts

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- Music

- The Japan Foundation Awards

- Cultural Diversity

- Japanese Studies

- Japan

- Mexico

- Tambuco Percussion Ensemble

- Percussion instruments

- Seiji Ozawa

- Yuriko Kuronuma

- Toru Takemitsu

- Midori

- Ikuma Dan

- Naoyuki Miura

- Toshiko Akiyoshi

- Wolfgang Sawallisch

- Latin America

- Akira Nishimura

- Jo Kondo

- Takehito Shimazu

- Keiko Abe

- Ricardo Gallardo

- Akira Kurosawa

- Dodes'ka-den

- Marimba

- Claudia Calderson

- Raúl Tudón

- Alfredo Bringas

- Javier Alvarez

- Marcos Limenese

- Paul Barker

- Mara Granillo

- 20-string Koto

- Nanae Yoshimura

- Shakuhachi

- Kifu Mitsuhashi

- Masataka Matsuo

- Festival Internacional Cervantino

- International Society for Contemporary Music

- Héctor Infanzón

- Minoru Miki

- Miguel González

- Pre-Hispanic

- Afro-Caribbean

- Leopoldo Novoa

- Guacharaca

- Cajón

- Carlos Chávez

- György Ligeti

- Sándor Veress

- Katalin Karolyi

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…