"Butoh―The Great Spirit" Russian Tour

Takashi Morishita

Research Center for the Arts and Arts Administration, Keio University

Butoh started to gain international attention as early as the 1980s, but in recent years Japan's avant-garde dance form is generating a new wave of interest in the world.

One such example is in Asian countries, where Butoh formerly received minor attention but is reaching an increasingly broader audience. Another development is in countries that have welcomed Butoh from early on but where dancers and researchers are reflecting on and studying anew how Butoh has been received and understood over the years.

This latter phenomenon is represented in the work of French scholar Sylviane Pages, "La réception des butô(s) en France: Représentations, malentendus et desires" (The Reception of Butoh in France: Misunderstandings and Desires), which she presented at Keio University's International Butoh Conference in January 2009. Pages later produced a doctoral thesis with the same title.

Also, Christine Greiner, a Brazilian researcher of body language theory and dance, delivered a speech last year at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies entitled "Butoh: A Dance Experience to Recreate the Body Beyond East-West Dichotomies" in which she discussed the various aspects of Tatsumi Hijikata's Butoh, Butoh's diaspora in the Western world, the symbolic meaning of Kazuo Ohno's death in the West, and the impact Butoh has had on Brazil, France, the U.S., and Argentina.

As head of the Liaison of International Butoh (LIB), I have been traveling abroad almost annually in recent years, planning and organizing Butoh performances around the world. I have teamed up with different Butoh dancers and musicians for each tour and done my best to meet the expectations of audiences in Russia, Italy, Brazil, Indonesia and Hungary. Originally, I had no overseas tour planned in 2010, but the Japan Foundation called on me to coordinate the events it was sponsoring in Russia in November 2010 and in China in March 2011, an invitation which I happily accepted.

What follows is a report on the recently completed Russian tour, focusing on the reception of Butoh in the country.

Stage performance in St. Petersburg

Stage performance in St. Petersburg

Launch a project --off to Russia

The project aimed at introducing Tatsumi Hijikata's Butoh to Russia and China was launched in July 2010. "Butoh--The Great Spirit" consisted of a tour program featuring a broad range of events and activities including workshops, film screenings, photo exhibitions, and lectures, with the highlight being stage performances. For the stage performances, I recommended Yukio Waguri and Moe Yamamoto, artists who had endured rigorous training in Tatsumi Hijikata's dance studio Asbestos Hall during the 1970s, when Hijikata's Butoh was at its pinnacle. They were perfect for the job in that they frequently traveled abroad giving performances and holding workshops. Yukio Waguri agreed to go to China, and Moe Yamamoto to Russia.

On November 17, the team heading to Russia gathered at Narita International Airport: Butoh artists Moe Yamamoto and Kei Shirasaka, and production manager Teruko Suzuki, from the dance group Kanazawa Butoh Kan; lighting director Masaru Soga; sound designer Rui Yamamoto; Yoko Kitagawa from the Japan Foundation; and myself, in charge of the exhibitions and lectures. Back in September, I had gone with Yamamoto and Kitagawa on a preliminary mission to Russia. On both trips, the Japanese Consulate in St. Petersburg and the Japan Foundation, Moscow kindly assisted in making overall arrangements in the respective cities.

Feels like a "return" to St. Petersburg

Once we arrived at St. Petersburg, we had a full schedule the following day: a press conference in the morning, followed by a lecture starting from the early afternoon. These were held at a gallery run by the Chemiakin Foundation owned by the Russian painter Mihail Chemiakin. In this gallery--which had a spacious hall more like an auditorium--we set up photographs from Eikoh Hosoe's Kamaitachi photography book and Tadanori Yokoo's posters to display. This being the third Butoh performance in St. Petersburg, we had anticipated a warm reception of our program. In the presence of 20 or so reporters, the press conference began with opening remarks by Satoshi Matsuyama from the Japanese Consulate and Yoko Kitagawa from the Japan Foundation as hosts, followed by Moe Yamamoto's lecture on the piece he was to perform, Fukuchu no mushi (Bug inside the Body). Describing a Butoh piece in words is never easy, and this was no exception. There came a stream of questions about Butoh. The reporters were not interested in obtaining superficial information; they asked some fundamental questions, such as what led to the birth of Butoh in Japan and what made the Europeans accept Butoh. The Russians, like all audiences abroad, were seeking clear answers.

In my first lecture of the tour, held in the afternoon, I talked about the history of Butoh while showing a slide show of Hijikata on stage. When I say history, I do not mean a chronology of events. The audience wanted to hear about the circumstances that led to the birth of Hijikata's Butoh and other fundamental issues surrounding it, an explanation that would shed light on the ideological challenges of Butoh. A strong interest and enthusiasm in Japanese culture underlay the audience's genuine desire to understand Butoh in its proper context. By this time, no one associated the atomic bombings with Butoh, as many people did decades ago, but instead, some wanted to know the role of Buddhist philosophy in Butoh. While Tatsumi Hijikata has not acknowledged any religious influence on Butoh's creation or principles, I suspect one can establish some measure of similarity between Butoh and Buddhism.

I occasionally say "Butoh is zen in motion" as a joke, but in fact this definition might be useful for foreign audiences to understand what Butoh is really about. Indeed, Butoh does take on religious characteristics if we consider it an art that gives us guidance as to how we should live our lives, and if we believe that its essence lies beyond expression. I am certain the Russians are attracted to Butoh's spiritual aspects.

Hence, "The Great Spirit"--as you can see, we came up with this title for a good reason.

Lyudmila Lipeiko, the director of Art Center BEREG who made all the venue arrangements for our program in St. Petersburg, told me the local people had been looking forward to Japanese Butoh coming to their city. And she was right: there are definitely people in dance circles and Butoh fans here who are eager to see and learn about Japanese Butoh.

The press conference and lecture were followed by Moe Yamamoto's workshop. However big it was, the hall packed with 40 to 50 participants generated so much heat that we had to open the windows to let in fresh air. Some participants were quite old. One was planning to translate a book about Butoh written in English, and another expressed his wish to go to Japan and study Butoh in depth.

This was how our first day in St. Petersburg unfolded. Observing in person the Russian people's unchanging interest in Butoh, I was engulfed with the feeling that I had "returned" to St. Petersburg.

Butoh was first introduced to Russia, and to St. Petersburg in particular, by the country's very own dance company DEREVO. It was also DEREVO that created the first opportunity for Japanese dancers to perform in Russia. Anton Adasinsky, the founder of the group and a fan of Kazuo Ohno, happened to see a stage I helped organize in Japan and invited me to produce a show together in Russia, which resulted in a Butoh-DEREVO collaboration in 2005.

We performed only in St. Petersburg at the time, but to my surprise the six-day tour attracted a crowd of nearly 1,000 each evening. The tour was entitled "Mad in Japan," and I brought a number of young dancers and musicians from Japan who had never met Hijikata, as well as experienced artists such as Koichi Tamano and Moe Yamamoto who studied directly under the master. Each stage was overflowing with energy reminiscent of 1960s Japan, not so much from the Japanese Butoh performers but from the wild and intense stage act by DEREVO.

(Top & bottom) Butoh workshop in St. Petersburg

Russia: A country with a lunchtime radio show about foreign culture and religion

The next day, I had an interview on a radio show and then lectured at a theater school. On arriving at the radio station, I learned that my interview was part of a 30-minute live program called "Art-lunch." The hostess was to ask me some questions, which I was to answer. As soon as they finished explaining the procedure, they cued start and we went on air.

After I finished a general outline of Butoh, I answered a series of questions about Butoh's current state and its reception overseas. Here again, I was asked if Butoh had anything to do with Buddhism. As I responded to each question, I wondered: Weren't the radio audience mostly just regular folks and not necessarily, say, art lovers or intellectuals? Apparently, in this country a radio show discussing foreign art and religion, during lunch break, was the norm. If you ask me, that is intriguing enough to arouse my interest in Russia. Lipeiko later told me she listened to the program and found it interesting. At my next stop, the theater school, the instructor was initially worried about low attendance since his class was not mandatory, but his fear proved unfounded. When it came time to start, all seats were occupied in the classroom, albeit a small one. In the audience were some members of the general public as well as theater students.

Interview at the radio station in St. Petersburg

The success of the tour hinged on the outcome of the stage performance. It was scheduled at Litsedei Theater, which we were able to book for just two days: one for preparation and rehearsal and another for the actual performance. While I appreciated that it could not be helped, I found it unfortunate that we could hold only a single show. On the eve of our first performance in Russia, lighting director Masato Soga went about his work with the poise of a veteran in an unfamiliar theater, and performers Moe Yamamoto and Kei Shirasaka silently worked out, getting ready for the show.

The day of the stage performance, November 20, arrived. Litsedei is a medium sized theater with some 400 seats. Large white sheets of paper were hung from ceiling to floor on both sides of the up-stage area and the audience-right side of the down-stage area and illuminated by a soft light. Soon, the audience began to enter as if to release the pre-performance tension that had been building up. When time came to open the act, spectators were still pouring into the theater. The impatient crowd already in their seats clapped, urging us to get started. It was well past curtain time when Moe Yamamoto and Kei Shirasaka finally took to the stage and Fukuchu no mushi began.

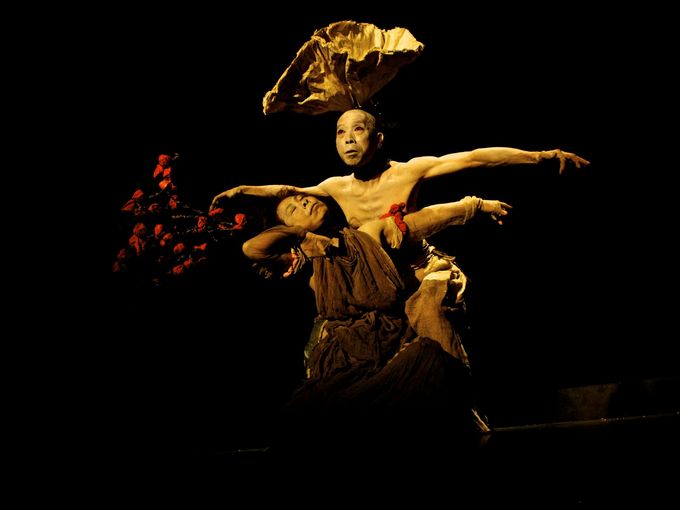

Moe Yamamoto made slow, cautious moves while Kei Shirasaka danced briskly, as if floating on stage. The contrast was striking. Despite being short, the program was composed of a wide variety of scenes and was fascinating to watch. I would imagine that many people who saw Butoh for the first time this evening found the performance strange yet highly impressive. During the finale, the two dancers, perhaps from the satisfaction of having completed their work, bowed to the audience with entranced expressions. Responding to a great round of applause, Yamamoto even stepped up to the front of the stage and, with bouquet still in hand, did a slide across the floor. The applause got even louder, and some yelled, "Bravo!" On this night we had more than a full house, with some people in the standing area. Our St. Petersburg performance ended a success.

After the performance, we screened films of Nikutai no hanran (Rebellion of the Body), and Hosotan (Story of Smallpox). Applause went up after each. Next up was dance critic and researcher Kazuko Kuniyoshi, who lectured about the current state of Japanese contemporary dance. It was after half-past nine at night, but more than 100 people stayed in their seats, listening intently to the lecture.

(Top & bottom) Stage performance in St. Petersburg

Moscow performance--end of the tour

On November 22, the team moved on to Moscow. We had a little more time here: one week.

All our programs took place at the School of Dramatic Art. We did not know at first that despite being a "school," this was not an institution where students were taught and trained, but a facility that staged experimental theater. The school owned several halls and studios, and presented avant-garde drama in accordance with a unique theatrical philosophy of its own.

The exhibition in Moscow. The two pictures are printed on loosely woven cotton commonly used for agricultural purposes.

(Left) Venues in both St. Petersburg and Moscow displayed the same exhibit: photographs and posters, and also films in small projection rooms.

(Right) The framed pictures are original prints of Eikoh Hosoe's Kamaitachi.

For this tour, we had produced a Japanese-Russian bilingual pamphlet entitled "Tatsumi Hijikata's Butoh--The expression of artistic philosophy and the philosophy of physical expression," which was printed in Moscow and distributed to interested parties during the tour.

Having reviewed the information on this pamphlet prior to my lectures, some audiences asked tough questions that I was hard put to answer. They wanted to know, for example, how to evaluate the sheer variety in forms of Japanese Butoh, and what the specific differences were between Kazuo Ohno's Butoh and that of Tatsumi Hijikata--questions that I could not possibly answer in a word or two. The fact that I had not prepared any notes for my speeches, in addition to the fact that the questions raised were unpredictable and challenging, must have made the job of my interpreter quite perplexing. Tarasova assured me, nevertheless, that it was all very thrilling and interesting.

This tour of Russia was a meaningful experience for me, too, because never at events aimed at discussing Butoh in Japan do I get so many questions or comments from the general public.

In Moscow, we staged Fukuchu no mushi twice--once each on two days--not at a theater but at an improvised studio. The first show somewhat fell short of our expectations, but on the second night every detail of the performance, including lighting, was precise and well-presented. Granted some of the spectators were invited guests, we had a full house on both nights. Perhaps there were more experts in the audience than ordinary people, given the venue. I saw largely the same faces throughout the program, from the film screening to the lecture to the stage performance. They were apparently quite eager to absorb Butoh. Whatever the composition of the audience, we succeeded in showing Butoh to a large number of people in Moscow. On the days of performance, I had interviews for a TV program and a couple of radio shows. The media wanted to know the reason for all the attention and acclaim that Butoh receives outside Japan.

Thanks to the meticulous support of all individuals involved in organizing this tour, the team members were able to focus on their work without any distraction. What remains to be seen is whether Hijikata's Butoh reached the hearts of the Russian people.

In this tour that we named "Butoh--The Great Spirit," did we succeed in having an impact on the Russian people's spirits? In all likelihood we will find out someday, one way or another. One thing is certain: the trip has made us recognize once again that there is a great interest in Butoh in Russia.

From February to March 2011, we will be taking the program to China. We will perform only in Beijing this time, but it will be one of a handful of Butoh performances ever to take place in the country. No doubt it will be a tour filled with expectations and anxiety.

While I acknowledge that government regulations are more pervasive in China than in Russia, what is important for successful cultural and artistic exchange is the effort to build up the experience. There is reportedly an increasing interest in Japanese culture and arts in China, so I am looking forward to experiencing an energy and excitement similar to Russia, while I attempt to communicate with the Chinese people through Butoh.

photo by Svetlana Karlova

Takashi Morishita

Tatsumi Hijikata Archive, Research Center for the Arts and Arts Administration, Keio University

Born in 1950, Morishita has been involved in the production of Butoh performances since 1972 as a member of Tatsumi Hijikata's Butoh studio Asbestos Hall. After working at a publishing company, on the occasion of Hijikata's death in 1986 he participated in the establishment and management of the Tatsumi Hijikata memorial museum. He has since engaged in planning and organizing exhibitions and symposiums related to Hijikata.

Today, Morishita manages the Tatsumi Hijikata Archive located in the Research Center for the Arts and Arts Administration at Keio University. He is also a part-time lecturer in the Faculty of Letters at Keio University and representative chairman of the NPO Butoh Souzou Shigen. His literary works include Tatsumi Hijikata, Butohfu no sutoh--kigou no souzou, kouhou no hakken (Tatsumi Hijikata, Butoh Based on the Dance Score--The Creation of Symbols, the Discovery of Method).

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2022.11. 1 Inner Diversity<3> <…

- 2022.9. 5 Report on the India-…

- 2022.6.24 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 7 Beyond Disasters - …

- 2021.3.10 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2020.7.17 A Millennium of Japa…

- 2020.3.23 A Historian Interpre…

- 2019.11.19 Dialogue Driven by S…

- 2019.10. 2 The mediators who bu…

- 2019.6.28 A Look Back at J…