Beyond Disasters - Telling the Stories <4>

Ishikura Toshiaki, Art Anthropologist, Associate Professor at the Akita University of Art, contributor

Rethinking Stories - From The Story of Ishi to "Cosmo-Eggs" (Part 2)

July 29, 2022

[Special Feature 074]

Special feature: Beyond Disasters - Telling the Stories (Special feature overview here)

Myths and history are passed down from generation to generation. How are these stories from the past told and updated, transforming them into stories that transcend time and place? And what feelings did anthropologist and mythologist Ishikura Toshiaki instill in his work, "Cosmo-Eggs", recreated for exhibition at the Japan Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia, based on his research of myths throughout the world? Welcome to Part 2 of our special feature.

(See Rethinking Stories - From The Story of Ishi to "Cosmo-Eggs" (Part 1) here.)

Rethinking Stories - From The Story of Ishi to "Cosmo-Eggs"(Part 2)

Ishikura Toshiaki

4. The proliferating Story of Ishi

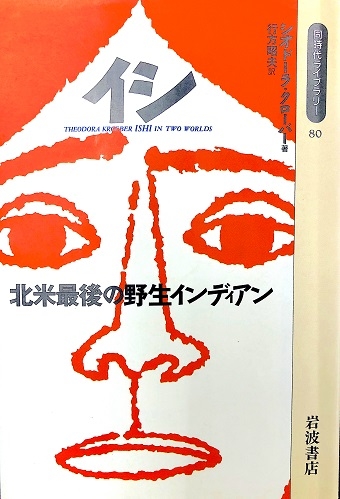

In the legends retold by Theodora Kroeber in The Inland Whale, we sense the anthropological fascination with trying to connect with the stories of others in completely different society and time from one's own, which she does with evident academic curiosity and bold imaginative flair. She then went on to write Ishi in Two Worlds on behalf of her husband Alfred (Japanese title, "Ishi: The Last Wild Indian of North America"), which brought Theodora Kroeber to the attention of the wider world. *1

Before the arrival of Columbus, the native peoples of the North American continent lived in their own civilization. After Columbus, they were subject to persecution and genocide by European colonizers and exposed to the devastating infectious diseases they brought with them. The story of Ishi, a man who lived alone in the wild after being separated from his family as they escaped an attack by the white man, tells the reality of colonization not easily found in the official record and is passed down through the generations. As Kroeber's daughter, Ursula Le Guin, describes Ishi being "A survivor of the extinction of the American Indians that was on a par with the Holocaust"*2, this tragedy was the dark secret of California and the United States as a whole.

Theodora Kroeber, Ishi: The Last Wild Indian of North America, translated into Japanese by Akio Namekata, Iwanami Books, 1991.

Theodora Kroeber, Ishi: The Last Wild Indian of North America, translated into Japanese by Akio Namekata, Iwanami Books, 1991.The legend evoked by Theodora is an unusual one about a "dying race", in that it is the story of the miraculous survival of a man, the last of his tribe who lived for five years at the University of California Museum of Anthropology. As meticulously described by anthropologist James Clifford *3, for the Kroeber family, The Story of Ishi might be something like a suture able to help mend the gaping wound of the devastating fall of Native Americans that lies behind the glorious dream of America, a country celebrated for its cultural diversity.

It is clear that the Story of Ishi presents a dual narrative challenge through "two worlds": past and future, the tribal world and the white man's world. One is the silence of the man called Ishi himself: not once from the time he was discovered until the end did he announce his own name. "Ishi" was not his actual name but rather a generic name bestowed by an anthropologist for the sake of convenience on a native man found in a pitiful state one morning in 1911 in a ranch corral, cornered by a dog. The word "ishi" is Mill Creek Indian for "man". Until his dying days in the last throes of tuberculosis, he never revealed his true name.

The other narrative difficulty concerns Alfred. For an anthropologist who had written detailed guides to native North Americans and spent his life researching the Indian tribes of California and had taken Ishi into his care at the museum where he was the Director, to tell his story as the "last member of a dying tribe" who was eventually subjected to autopsy against his will, would have been an unbearable task. After Ishi's death, when the possibility was raised of performing an autopsy for the sake of science rather than burying him in accordance with his wishes, Alfred was outraged. Until the day he died, Ishi was the subject of observation as "the last wild Indian" and after his death, his corpse was delivered for autopsy against Alfred's wishes and his brain stored at the museum. *4

Theodora moved beyond the narrative difficulties of the two men to portray half of the life of this rare individual who moved between the tribal world and civilization, sharing his story with the whole world. However, that was not the end of the story. In the 1990s, well after the passing of the Kroebers, Native Californian tribes closely related to Ishi launched a lawsuit based on the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act demanding the return of Ishi's remains.

The story lurches forward dramatically with the discovery of Ishi's long-missing brain in a storage vault at the Smithsonian Institute. On April 5, 1999, a formal hearing was held at the California state legislature in Sacramento on "Ishi's Brain and Reparations" where the Berkeley Anthropology faculty made a formal apology and reflected on its past treatment of Ishi's remains. In August 2000, as a result of negotiations among several groups, Ishi's brain, retrieved from storage and his ashes, which had been kept at the Mount Olivet Cemetery, were returned to a small delegation of the Redding Rancheria and Pit River tribes. The burial took place in private in the presence of non-native museum staff. A few weeks later, tribesmen and anthropologists held a two-day long dance at the Summit Lake on Mount Lassen to celebrate the occasion and find healing. *⁵

The image of Ishi as the "last wild Indian" created by Theodora was only ever a white-centric story. However, it is a story that has repeatedly been picked up by native and non-native American creators rethinking indigeneity in North America such as artists James Luna and Frank Day, writer Gerald Vizenor, and documentary makers Jed Riffe and Pamela Roberts. It has proven over and over again to be a fount of artistic creativity. *6

As Clifford writes, the story of Ishi has gone beyond simply rescuing the past to also become a story about the multiple futures of native peoples, expanding to cover a range of modern artistic endeavors. Even Theodora's daughter Ursula K. Le Guin is involved in its retelling and recreation. In her important novel, Always Coming Home*7, Theodora's family story of Ishi is transformed into a new version: a "story about the future". For Clifford, Le Guin's utopia - in which people "becoming 'indigenous' after colonization, crafting traditional futures in transformed places"*8 - is a vital historic project. In this new place where multiple memories and stories mix, the historic wounds and silences of Ishi's Story are healed. A plethora of images emerge to become future memories.

5. The story of the "Cosmo-Eggs"

How has the Kroeber family's story of a Native American man been reinterpreted in a way that has the power to move historical understanding and social reality in the United States of the 21st century? How has Ishi's story proliferated beyond the cruel tragedy of Indian extinction to become a rich source of inspiration in modern art? It is not easy to find a response, but it may be said that despite the silence and the difficulties, the effort to reimagine the story and to pass it on itself resembles the logical structure of legend, exploring complex historical realities through multiple versions of a story that about certain events.

Overcoming tragedy to rediscover history and reimagine a story does not necessarily imply averting one's gaze from disastrous events, nor does it imply complicity in fake news or historical revisionism that violates the silence of those involved who have no voice. No, it opens the process of history into a space for ongoing deliberation on the future. At times it might even occasion deeper exploration of the meaning of events, beyond fact checking and the designation of events as good or bad. This, which is above all an effort to understand others' histories, is a challenge that we should be careful of when facing a mythic reality that combines fact and fiction. Legends in which communities place great stock contain important historical truths. These can be gleaned from dialogue with those others. This shared historical practice is what was uniquely described by late historian Hokari Minoru as "doing history" *9.

Simple categorization is impossible, but when I was involved in a project in the Japan Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale international art exhibition to investigate the stories told about earthquakes and tsunami endured by the Miyako and Yaeyama islands, and to create new legends, this is what we had in mind.

Our project concerned "doing history", something beyond a local oral history of disasters. It started with the image of a tsunami boulder encountered by artist Shitamichi Motoyuki. "Tsunami boulder" is simply the name that the islanders gave to the enormous rocks left on the shore. The tsunami boulder captured by Shitamichi is more than a rock, it also contains part of the uplifted coral reef and is a monument that stands for the damage caused by the tremendous waves that threaten this region every few hundred years and most recently, the 1771 Great Yaeyama Tsunami. However, traveling around the islands, we discovered that these simple historic monuments have such a unique shape that they have been made part of playgrounds in parks, are used as part of people's homes, are made sacred as part of utaki (Okinawan for sacred place), or are just left in the middle of fields for no apparent reason. Some are left at the water's edge, where they become part of the scenery heralding low tide.

Visiting the island with Shitamichi, we walked around asking locals how they got there and their names. Interestingly, it was extremely rare for a tsunami boulder to be linked to a major local myth or legend. Instead, there is a love story about an official from off the island and a local girl, the legend of a mystery castaway who washed up on the island and other semi-historical anecdote fragments, which have been extended to explain the provenance of the rocks. In these southern islands, where a lot of legends are told, the tsunami boulders are surprisingly not the subject of fabulous tales. Rather, they have accumulated fragmented episodes told in the humdrum manner of a newspaper article.

The actual tsunami boulders are a world of their own, attracting migratory birds and insects to the plants and trees that grow around them. However, they are not an element in any unified historical narrative that would connect the islands. Nevertheless, extending the survey to the stories told around the individual tsunami boulders that at first sight appear to be strewn around the islands, a surprisingly rich folklore emerges.

Fieldwork at the Tsunami Boulder on Tarama Island, Okinawa Prefecture (Shitamichi Motoyuki is at right)

Fieldwork at the Tsunami Boulder on Tarama Island, Okinawa Prefecture (Shitamichi Motoyuki is at right)In parallel to the local survey conducted with Shitamichi, I persevered with my research on the myths and legends of the Okinawan islands, particularly the story of the tsunami-raising fish that is especially well-known on Ishigaki and Irabu islands and the tale of the egg-producing girl told throughout the Miyako islands and on Ikema Island in particular. In the former legend, a man catches a fish that can talk, and it calls on a tsunami to come to its rescue. In the latter story, a girl out sunbathing one day is quietly relieving herself when eggs fall out of her. These are said to be forebears of the islands' inhabitants. Both intriguing tales I encountered ten years ago during a trip to Miyakojima.

I had the idea of an exhibition to enhance understanding of the reality of the islands in a multidimensional way not just through the structural analysis of stories from different systems, but through the creation of all new stories. From there, I explored the relationship of cosmology and festivals with the contextual realities of the various stories, taking cues from the studies of anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss on myth and the study by a group led by folklorist Nakazawa Atsushi, anthropologist Nakazawa Shinichi and art critic Ishiko Junzo entitled, "Maruishigami: Shomin no naka ni ikiru kami no katachi" (Mokujisha, 1980).

The exhibition project members were curator Hattori Hiroyuki, artist Shitamichi Motoyuki, musician Yasuno Taro, architect Nosaku Fuminori and anthropologist Ishikura. The centerpiece of our collaboration was Shitamichi's video of tsunami boulders, and we came up with a plan to honor it by providing an audiovisual experience with an automated music player, a spatial experience by placing a giant balloon inside the Japan Pavilion's internal structure, and a folkloric experience with the creation of new legends based on those we had encountered in our research in the islands.

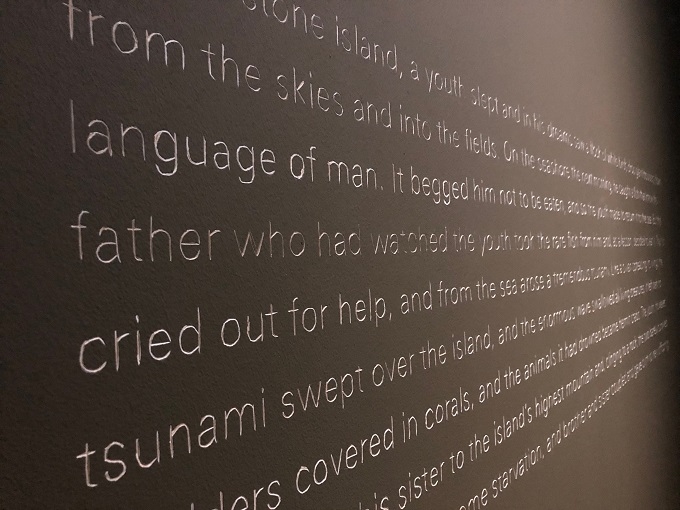

What we emphasized as a response to Shitamichi's "Tsunami Boulder" film was crosscutting art. This comprised the production of an automated music playing machine (by Yasuno) that would play the sounds of birds living in the vicinity of the tsunami boulders in the film (ajisashi - common terns and Ryukyu akashobin - ruddy kingfishers), production of an architectural space referencing the mobility of the tsunami boulders and the fluidity of earthquakes and tsunami in a way that utilized the structure of the Japan Pavilion (by Nosaku), and the etching into a wall of a new legend born from a reconstruction of the folklore and history of the islands (by Ishikura and the other members) *10.

[Cosmo-Eggs]

[Cosmo-Eggs] Exhibition at the Japan Pavilion, 58th Venezia Biennale International Art Exhibition (in exhibition room)

In studying how to make our plan a reality, I formed a desire to dream up a story that would connect the tsunami myth telling of "the end of the world" and the egg creation myth telling of "the beginning of the world". The film of Shitamichi and the music of Yasuno would also be playing continuously in the exhibition space. Against the backdrop of this repeating audiovisual and musical loop, I hoped to illustrate the history of several islands in a semantic story loop linking "the end and the rebirth of the world". I attempted to come up with a fictional myth that would sit in structural response to the art of Shitamichi's film loop and Yasuno's musical track loop, with fine variations according to the progress of the loop, with the aim of triggering a new viewing experience. *11

《Cosmo-Eggs | 宇宙の卵》

《Cosmo-Eggs | 宇宙の卵》

The text of the fictional myth etched on a wall

In fact, I struggled to replicate "beginning" and "end" in three different spaces, but it was a research visit to Taiwan in January 2019 where I had a revelation about how to realize my original idea - as a result of encountering a series of tales told about the arrival of a tsunami and the creation of the world from a stone. I was stunned by the formidable depth of history found in a number of folktales and legends, through the tribal tales of Taidong, the former colony of Japan. After returning from Taiwan, I set about writing the tale. The text of my fictional myth was translated into English and etched into the wall of the Japan Pavilion. In addition, my fieldnotes including research materials and recording my thought processes from the structural analysis of legends were all bound into a formal catalogue.

It was by extending the research scope of the "story" to Taiwan that our project gained its connection to reality - the fact that natural disasters surpass any national dividing lines on the map. This experiment was only made possible with the help of people everywhere we visited.

The situation in the Japanese archipelago, where the history of native groups has been passed down through the generations in the form of marginalized "island stories", encompasses different difficulties to the actions taken to apologize and compensate for native policy in the United States. For example, since 2008, the United Nations has recommended repeatedly to the Japanese government that it certify the indigenous status of people living in Okinawa, yet the government rejects the recommendation and is actually working to have it altered or repealed. The context of this denial is the existence from the beginning of an imaginative power strong enough to annex the islands of Okinawa to a history that is homogenous with that of the Japanese mainland. In the age of the modern nation state, a basically spatial system of order has governed the relationship between the Japanese and other peoples through the extensive island network, drawing an imaginary matrix over the islands of the Asia-Pacific.

However, across the Japanese archipelago and islands beyond its borders lie living, breathing "wild stories" that contain their diverse history in fragments of folk tales and legends. In the framework of our national pavilion at the international art exhibition, we wondered if we could shed new light on them. Would it be possible to display a story based on the diverse memories of the islands, or based on different survival stories for earthquakes and tsunami? The fictional myth in the Cosmo-Eggs exhibition at the Venezia Biennale International Art Exhibition was this type of folkloric experiment.

Just like the multidimensionally recreated story of Ishi, this tale is also told through tragedy. As shown by the "Cosmo-Eggs" title, the image of "multiple cosmic eggs" contains latent untapped realities. In the story, a sunbathing girl lays 12 eggs on her own. This is a motif that implies the spread of an egg creation myth told throughout East Asia and a robust genealogy of the imagination.

Myths and legends may not be a substitute for history, but nor are they mere playful fictions or tales to pass the time. They are a medium able to communicate certain common truths to future generations by invoking experiences or sensations that cannot be verbalized, bridging the gap between imagined things and things that actually exist. These stories surpass the writing systems built by humans, allowing humans to place the existence of other living and non-living things within society, and placing humans themselves in the localized worlds made up of those relationships. The mythical, imaginary egg not only opens up new artistic possibilities, it could help us to escape the human-centric universe that we know and reposition us within history on a planetary scale.

In the face of horrifying disaster and the memory of those who died before us, we can reassess our lives and create new stories that once again. These remade legends that go beyond the intersection of history and myth and overcome the difficulty of speaking of such things might just open the door to a human ethics that takes account of unknown realities.

- *1 Theodora Kroeber, Ishi: The Last Wild Indian of North America, translated into Japanese by Namekata Akio, Iwanami Books, 1991.

- *2 Ursula K. Le Guin, "Foreword: on the occasion of a new edition of Ishi", p. vii, in Theodora Kroeber, Ishi: The Last Wild Indian of North America, translated into Japanese by Namekata Akio, Iwanami Books, 1991.

- *3 James Clifford, "Ishi's Story", Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press, 2013.

- *4 The following book deals with the discovery and recovery of Ishi's brain: Orin Starn, Ishi's Brain: In Search of America's Last "Wild" Indian (English Edition), New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- *5 Clifford, "Ishi's Story". Details of the posthumous reassessment of the relationship between Ishi and the Kroebers is found in this blog: "Nancy Sheper-Hughes, Alfred Kroeber and his Relations with California Indians", July 24, 2020.

URL: https://blogs.berkeley.edu/2020/07/24/alfred-kroeber-and-his-relations-with-california-indians/ (last viewed July 2, 2021) - *6 Clifford, "Ishi's Story".

- *7 Ursula K. Le Guin, Always Coming Home, Harper and Row, 1985.

- *8 Clifford, "Ishi's Story".

- *9 Hokari Minoru, Radical Oral History: experiencing Aboriginal history. Iwanami Books, 2018.

- *10 Ishikura Toshiaki, Cosmo-Eggs: Exhibition at the Japan Pavilion, 58th Venezia Biennale International Art Exhibition - Tagui vol. 2, Akishobo, 2020.

- *11 Ishikura Toshiaki, "Fieldworking with Hybrid Gatherings―Towards World-Making from Archipelagos in East Asia," in Reflections on Cosmo-Eggs at the Japan Pavilion at La Biennale, Venezia, 2019. Torch Press, 2020.

Submitted July 2021

All photos by author

Related Articles

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…