11.Lands and Voices

――A Japanophone Taiwanese Goes on Swaying――

A couple of days had passed since the full moon. The moon floating in the sky looked much closer than usual, taking me by surprise. As I got off the car, I felt the piercingly cold air on my skin and the leftover frozen snow under my feet. Since I was expecting it would be very cold in Aomori, it did not keep me from admiring the sky.

It was not just the moon that fascinated me.

The stars, too, appeared incredibly close. Each star was dazzlingly brilliant, and this made me realize the sky I usually gazed up at in Tokyo appeared so distant.

"Come this way." I was taken to the Hachinohe Book Center, a "town bookstore," which was just launched by Hachinohe City as a public project.

Stepping through the polished glass-walled entrance, I was enveloped in a gentle coffee aroma that wafted through the bookstore. The brightly-colored floor and the high ceiling created a relaxing ambience. The layout of the bookshelves in the large open space allowed customers to freely roam among them without bumping into each other.

The books were not shelved in the order of the author's name in the Japanese syllabary, but according to their theme. There were various thematic categories, such as "Overview," "Think," "World," "How to Live," etc., and I was told that many customers spent hours absorbed in the books.

The most important characteristic of this store is that browsing is not banned; on the contrary, customers can sit on the chairs and sofas placed among the bookshelves and read books before purchasing them. Furthermore, there are coffee cup holders on the arms of the chairs and sofas, allowing visitors to enjoy a drink while reading. The bookstore offers not just a place to relax and read books. I was fascinated by the fact that there were also a facility for book club meetings and "confinement booths" perfect for people who wish to concentrate on their writing.

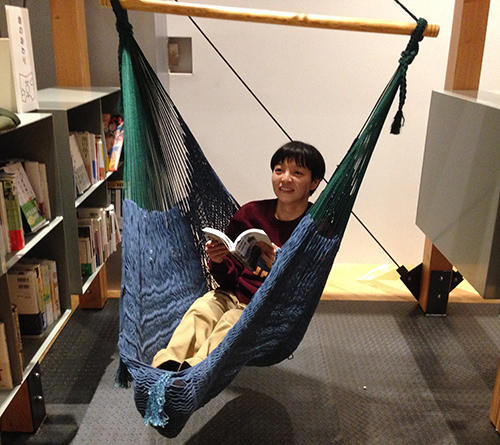

But the thing that excited me the most was the hammocks.

As I like riding on a swing above all others on the playground, I have always dreamed of spending all day gently swaying in a hammock. But, I do not very often come across a hammock.

However, there was a space where visitors can read while relaxing in a hammock at the Hachinohe Book Center.

Moreover, all visitors of the bookstore can use the hammocks whenever they were available.

Needless to say, I happily got into one.

It felt great!

I thought about how happy I would be if I could read a favorite novel while swaying gently in a hammock. But I bet I will doze off half way through the novel.

I was instantly captivated by the hammocks. Reading in a hammock was so relaxing that I almost dozed off.

As I was shown around the bookstore, I felt that the Hachinohe Book Center was a place where people who searched for, read, enjoyed, and loved books could explore their world.

It could also become a meeting place where people can come together around books.

The purpose of my visit was to participate in the events commemorating the opening of the Hachinohe Book Center together with novelist Sen Ishida and poet Keijiro Suga.

We were led to Hachinohe by novelist Yusuke Kimura.

I still remember the first time I read Kimura's novel Umineko Tsuri Hausu [Black-tailed Gull Tree House], which is set in Hachinohe, the home of the author. The characters in the novel, who are natives of Hachinohe, converse in a dialect that is different from the standard Japanese language. In his work, Kimura frequently employs sonant consonants in the dialogues, and freely uses the Nambu dialect spoken in Hachinohe. As a result, the book overflows with passion that would have been lost if the conversations were "translated" in the standard language.

One of the first reviews of Umineko Tsuri Hausu upon publication in a book format was written by Keijiro Suga. "Not knowing the pronunciation makes it difficult to re-create the accent. Yet, it fascinates me with its joyful and uplifting ambience, perhaps because I can feel the mental tension and courage of the person who, when sounds are first converted into characters, records these sounds."

In an interview upon receiving the 33rd Subaru Prize for Literature, Kimura said: "At first glance, it looks like Tokyo is the driving force behind Japan's modern social trends, but in fact, in this very moment, people are living in the rural areas and silently crying out, too. I want to listen to and preserve the voices of people in such unknown places."

As I was reading his interview, I felt a strong desire to meet this author and talk with him. Back then, I myself had just won an honorable mention in the 33rd Subaru Prize for Literature for my work Kokyokoraika [Poem wishing Godspeed], in which I shared my own language experience as a Taiwanese raised in Japan by using the katakana syllabary to convey Taiwanese sounds, and highlighting the presence of the Chinese language through simplified characters and traditional characters.

Soon, my wish came true and I became friends with Yusuke Kimura.

Later, while I was slowly and laboriously writing my next novel, Kimura published, in a constant succession, several works, including Seichi Cs [Holy land Cs], Isa no Hanran [Overflowing Isa], and Norabitotachi no Moeagaru Shozo [Burning portrait of stray people], that questioned Japan's contemporary social system and the widespread trend to cause hardship on the weak members of society.

In 2013, we joined a team of authors working on the text of Tokyo Heterotopia, an interactive play by Akira Takayama, upon an invitation from Keijiro Suga. We continued to collaborate through our involvement in the Tekken Heterotopia Literary Prize born from the play, and I was blessed with numerous opportunities to share with him precious inspirations for our creative work.

As authors who devoted ourselves to studying the craft of creative writing in our respective places inspired by the "desire to draw sounds into the world of the written word and write things that have never been written before" (quoted by Keijiro Suga), Kimura and I launched our careers as novelists simultaneously, and I cannot help but think that, at least for me, this was some kind of destiny.

A certain phrase suddenly pops into my head.

"Swaying forever."

That was the title of the review on Umineko Tsuri Hausu written by Suga.

Together with Suga and Ishida, I arrived in Hachinohe, where Kimura was waiting for us. The long-awaited events to commemorate the opening of the Hachinohe Book Center began the next day.

For the first part of the events, which was a workshop, we split into two pairs--Suga and Ishida in one pair, and Kimura and I in the other--and interacted with readers. The ten participants in our group had to read in advance my novel Raifuku no Ie [Blessing House], which was the starting point of our discussion. As I listened to the straightforward opinions on my work expressed by book lovers from Hachinohe and its suburbs (some participants had come from as far as Aomori City), I was gradually taken over by the thrilling sensation that I was given the most gratifying experience an author of a book could wish for.

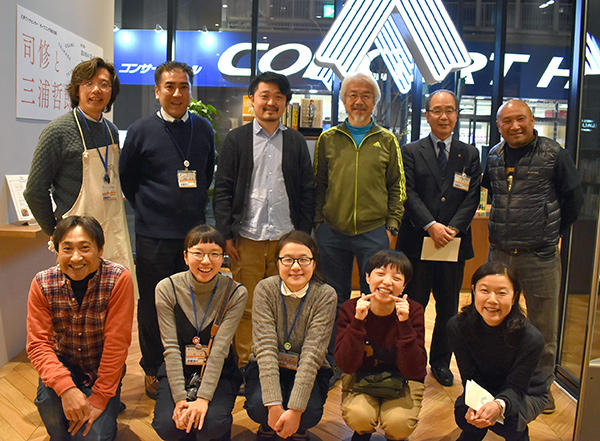

Suga (back row, third from right), Kimura (front row, far left), Ishida (front row, far right), and the staff members of the Hachinohe Book Center. With my fingers I am making the shape of the Chinese character "hachi," which is used in the name of the city Hachinohe.

The youngest participant in the workshop was a student at the Hachinohe Institute of Technology.

He stated somewhat hesitantly, "When I read a book I always place myself in the position of its characters." He then went onto say, "The main character does not know if she is Japanese or Taiwanese. If I were in her position, I think I would get squished."

Get squished.

This frank opinion brought back a rush of long-forgotten turbulent emotions.

When I was writing Kokyokoraika, every day I felt as if I got squished. Every night, I sat in front of the computer typing with intense devotion, as I struggled to capture the sensation of living in the moment. Perhaps for me the act of writing was a way to confirm that I really existed.

Only when I wrote did I feel like I would not get squished. That is why literature was indispensable for me. As I spoke about the great encompassing power of literature to the university student and the rest of the participants in the workshop, I felt like I was trying to convey this "truth" to my former self.

After the end of the workshop, we joined Suga and Ishida for a talk event on the theme "Lands and Voices." As we traveled to the next venue, Kimura mumbled: "I hope this book center becomes a safe haven for people struggling to find an exit."

I found myself agreeing with him.

Literature has the power to provide emotional support to those who become confused, helplessly unable to find their place in life. It also embraces them, and makes them feel welcome and accepted. I believe that as long as books are the entry to literature, people will need places where they can encounter books.

Therefore I hope from the bottom of my heart that the earnest efforts of the people working on the Hachinohe Book Center project, who are struggling to create and foster a hub that links people and books, will be rewarded one day even if it is in the distant future.

The talk event in the second part attracted an audience of approximately 70 people. In the opening of the event, Suga, Ishida, Kimura and I read our works on the theme "Lands and Voices" written especially for this event.

I read a text titled Mūi no Yuwaku [Temptation of mǔyǔ].

The reason behind this title is that mǔyǔ is the Chinese pronunciation of the characters that mean "mother tongue." If "native language" is the language that defines belonging to a certain nation, then "mother tongue" is an even more basic concept. It refers to the language a baby hears from its mother or a person who looks after the baby instead of the mother.

That is why my mother tongue (mǔyǔ) is Japanese mixed with a lot of Chinese and Taiwanese.

As I prepared for my trip to Hachinohe, I started to have an even bolder interpretation of mǔyǔ, which is not something imposed by other people but a language that is unique to each individual.

Realities that might just disappear if conveyed in a standard language, or local dialects filled with fervent ardor, for instance. I am sure that such languages that cannot be separated from the land where they are spoken are reverberating in various places throughout Japan in this very moment.

"I think that dialect words that lose something of their meaning when translated or standardized contain an important message."

This is a quote from an old interview with Yusuke Kimura.

People who spend all their time in Tokyo tend to forget that Japan is not a monocultural or monolingual country. It is much more diverse than we imagine and has a rich breadth.

In Hachinohe, the place that has nurtured the mǔyǔ of Yusuke Kimura and his friends, I quietly tried to imitate their way of pronouncing the name of the city. Not Hachinohe, but Hajinohe.

Hajinohe, Hajinohe.

I felt as if the word infused a breath of fresh air in my Japanese language, and the experience filled me with excitement. If I had had more courage, I would have tried using the local expression of agreement "nda, nda," instead of just nodding, but I was too shy and gave up.

This is how the evening deepened into night in Hachinohe.

I stayed up late and reflected over the events of the trip as I always do on the last night at my destination. I had the booklet titled Lands and Voices at hand. The beautiful illustrations that harmonized with the texts written by Suga, Ishida, Kimura and myself, were created especially for this project by one of the core staff members of the Hachinohe Book Center Hanako Mori.

Mūi no yuwaku, a text I wrote on the theme "Lands and Voices." The drawing created by Hanako Mori is lovely!

Spread on the hotel's single bed, I read Ishida's text titled Hanarete, damatte [Step away, Stay quiet].

"A lot of time wriggles by the first breath. The places I've been to and the places I am in circulate in my body, get together and then part away. There is no need to listen eagerly, to worry about the weather tomorrow, or to open maps and trace routes. The lands and the voices are so close by that I can not only touch them; they are about to be absorbed into all over my body."

It was a truly blissful time in which I savored, both with my eyes and my fingers, the lush and vivid writing of Ishida, while her soft and gentle voice still resonated in my head as we had parted just moments ago. It made me re-live the relaxing experience of swaying in one of the hammocks at the Book Center.

Next time I will come to Hachinohe to hear the cries of the umineko. I want to meet again the staff of the bookstore and the charming people in the town that Kimura introduced to us.

As I reminisced about this, I indulged in the happy thought that the number of cities I loved kept increasing.

Dawn was about to break over Hachinohe. I gave up on the idea of visiting the Tatehana Wharf Morning Market, one of Japan's largest morning markets, so that I have an excuse to visit Hachinohe again. I squeezed my eyes shut, trying to quell the happy excitement that filled me.

I always struggle to convert rustling feelings inside me into written words. I really should learn to fully open my ears, eyes, and mind, accept the flow of events and things around me and blend with it, and flexibly expand the boundaries of my world when I am away from home in a strange land sometime. With this thought, I finally fell asleep.

This time, my essay turned out quite long.

The truth is, this is the final installment of the series "Japanophone Taiwanese, That's What I Am!"

I must say farewell to you here. I will continue to nurture my Japanese as I travel around Japan and Taiwan, two countries with diverse cultural landscapes, and my heart will go on "swaying."

I am sure that we will meet again someday, somewhere!

Follow Wen Yuju on Twitterhttps://twitter.com/wenyuju

Related Articles

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…