8. Encounter of Two Authors: A Japanophone Taiwanese Meets a Taipei Person-to-be

When in Taiwan, I always stay at my father's "home" overlooking the Tamsui River. It is a three-bedroom apartment that my father purchased to accommodate his needs as he spends more time in Taiwan than in Japan. There is my parents' bedroom and my father's study. In the spare bedroom, there are two single beds and two desks. My father says that these are for me and my younger sister. So for us, my father's "home" in Taiwan is another family home in addition to our house in Tokyo, where my mother lives.

The windows of our "family home" in Taiwan offer a sweeping view of the waving flow of the Tamsui River sparkling in the sun. On clear days, the quietly majestic Mount Guanyin is distinctly visible in the distance. After I learned that mangroves can put roots both in the sea and on land, I liked the view from the apartment to the river overgrown with thick and luxuriant mangrove forests more.

Last November, I spent several days at that "home."

I was in Taiwan because of an invitation by Professor Shozo Fujii to participate in the Taiwan-Japan Writers Exchange Forum as a Japanese author.

This "Literature Meeting" organized by Chinese Language and Literature Course, the University of Tokyo, where Professor Fujii teaches, and Trend Micro Education Foundation of Taiwan is a symposium composed of round-table discussions and lectures that aim to promote exchanges between Japanese and Taiwanese fellow writers. The first such symposium was held in November 2013 at the University of Tokyo. There, I participated in a talk on the theme "Parting with one's grandparents" together with Gan Yao-Ming and Yang Fu-min. Although it was conducted through interpreters, this talk with two authors whose home and source of inspiration for creative writing is Taiwan, the country of my grandparents and my great-grandparents (if we go back one generation further), was extremely interesting and left a very strong impression on me.

Later, Gan Yao-Min's collection of short stories Shénmì lièchē [Mysterious Train; the Japanese edition's title: Shinpi Ressha] was translated into Japanese and published by Hakusuisha. Also, Yang Fu-min's short story Tīng bù dào [Unheard; the Japanese title: Kikoenai] was published as part of the series introducing foreign authors' works in the November 2015 issue of the literary magazine Subaru.

This discussion on the theme of creative writing with Taiwanese authors of my generation was a truly invaluable experience for me. It made me consider various questions: Would I still have wanted to write novels, had I not moved from Taiwan to Japan, and if so, what kind of novels would I have written?

The second symposium took place in November last year in Taipei. As one of the organizers of the event, the Graduate Institute of Taiwan Literature at the National Taiwan University provided the venue for the symposium, which was held at the University Hall.

I took the stage together with Chen Yu-chin, a writer of the same age, in a session moderated by Professor Wong Yinzhe at the Faculty of Modern Chinese Studies of the Aichi University. Both Yu-chin's name and my name are written with a certain Chinese character pronounced "yu."

We also share a very similar look in terms of height and hairstyle.

In the beginning of the discussion, I jokingly said in Japanese: "We may look like each other, but we are not cousins." The moment the interpreter conveyed my words in Chinese, Chen Yu-chin's face broke into a smile, and I felt inexplicably happy.

A "Taipei person-to-be" and a "Japanophone Taiwanese" with similar names and height

It turned out that we shared not only a Chinese character in our names and a similar height and look, but also identical awareness on issues related to creative writing.

The daughter of a nationalist veteran soldier from mainland China and an Indonesian-Chinese mother, Yu-chin had eagerly read the Chinese translation of my novel Raifuku no Ie, which is narrated from the perspective of a child raised in a country that is foreign to its parents.

The majority of the population in Taiwan, including my parents, is Han Chinese. They have lived on the island of Taiwan since before 1949 and are also called "islanders." In contrast, the people who withdrew to Taiwan together with Chiang Kai-shek after his defeat by Mao Zedong in the civil war were called "mainlanders." They had sworn loyalty to Chiang Kai-shek, and many of them kept dreaming of returning to their homeland in China with the determination to restore their rule over the mainland. For them, Taiwan was a kind of "temporary base."

This, however, happened more than half a century ago.

Born and raised in Taiwan, their children and grandchildren are already adults.

To them, Taiwan is by no means a "temporary base," but rather their birthplace and the only home they have ever known.

Yu-chin is one of these children.

Furthermore, the native tongue of her mother, a woman who married a "mainlanders," is neither Chinese, nor Taiwanese, but Indonesian.

Yu-chin, a self-described "Taipei person-to-be" and I, a "Japanophone Taiwanese" hit it off immediately.

We both had mothers whose native tongue differed from the language we spoke, we both carried the awareness that we are not entirely Taiwanese/Japanese, and in our school days differed from our classmates in terms of our origins. Thanks to the skillful moderation of Professor Wong Yinzhe and the swift and precise work of the interpreters, our discussion titled by the organizers of the symposium "Where is my home?" advanced in an enjoyable manner while exploring profound issues.

My greatest regret was that, since Yu-chin's works had not yet been translated into Japanese, I could not read up on her as well as she read up on me. I had only glanced over one of her short stories translated by Professor Fujii especially for the symposium.

That is precisely why, however, when I parted with Yu-chin I felt that this was not the end, but the beginning of our relationship.

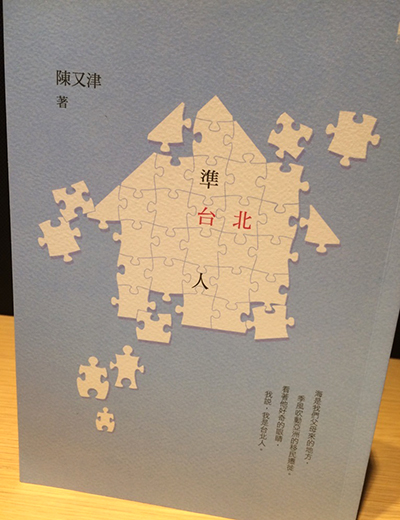

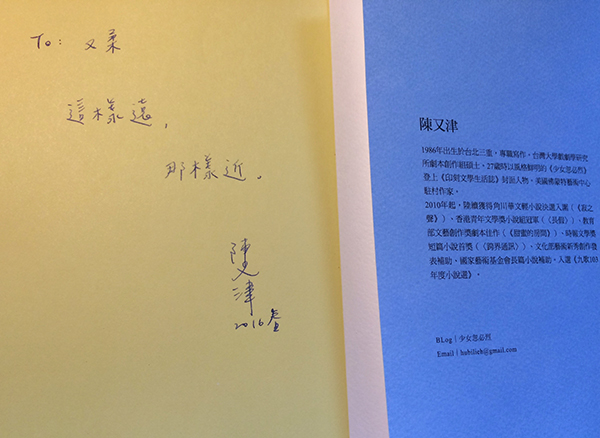

Left: Chen Yu-chin's collection of prose Zhuó-Táiběirén [Taipei People-to-be] published last November, just before the symposium

Right: "So far, so close" - a note Yu-chin wrote for me in Chinese

Later, we discovered through Facebook that we had a common friend.

According to that friend, it was destiny.

In Chinese "Yuju" sounds like "there is meat," and Yu-chin sounds like "there are tendons."

Spelt out in Pinyin, the Romanization system for Standard Chinese, our names overlapped with phrases that meant "there is meat," and "there are tendons." That friend of ours, who lived for a good joke, sent us the following message:

"I simply must go with the two of you for a bowl of beef noodle soup."

Beef noodle soup, or gu-bah mi in Taiwanese, is a noodle soup made with stewed beef Achilles tendon.

So, as my friend pointed out, if you put meat ("Ju") and tendon ("Chin") together, you get beef noodle soup--a dish in which "there is meat" and "there is tendon."

(In fact, when I visited Taipei again in February, we had a Beef Noodle Soup Party at his initiative, and celebrated a joyful reunion.)

The two-day Taiwan-Japan Writers Exchange Forum ended successfully, and on the last day of my stay in Taipei before my return to Tokyo the following morning, I sat at the desk in my room in our "family home" overlooking the Tamsui River and opened a notebook. I was polishing a draft of the first afterword I have ever written in my life, for my collection of essays Taiwan umare Nihongo sodachi [Born in Taiwan, Raised in Japanese]. Ever since I was a child, I have always felt most relaxed and at ease when writing in my diary or a notebook sitting at my desk or lying flat on my stomach on the bed.

"Where is my home?"

Suddenly, this question, which was the theme of the writers' symposium, popped in my head in Chinese. Whether in Tokyo or in Taipei, I cannot help but write in Japanese. In moments like that, I feel that perhaps the Japanese language is indeed my home after all. Information

【Information】

A dialogue between Wen Yuju and her mentor Hideo Levy titled "Reading Mohankyo [Model Homeland]: East-Asian time and 'me'" was published in the October issue of Sekai (The World), a monthly journal issued by Iwanami Shoten, Publishers.

Follow Wen Yuju on Twitter https://twitter.com/wenyuju

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…