5. Reading Taiwanese Literature Part 1 - To the Soldiers! by Huang Chunming

To be honest, I have never been very enthusiastic about reading Taiwanese novels, because, despite being Taiwanese, I have to rely on the Japanese translations and this makes every attempt to read Taiwanese literature a frustrating and slightly mortifying experience. A couple of years ago, however, I read a work translated into Japanese, which made me painfully aware of the fact that I had no time to feel mortified. The work in question, which gave me a powerful sense that there were many works of Taiwanese literature that I had to read, even if relying on the Japanese translations, was the short story Zhànshì Gānbēi! [To the Soldiers!] by Huang Chunming.

The narrator of the story, who it could be interpreted is the author himself, befriends an aboriginal youth, Mr. Pu, alias Xiong. Xiong takes the narrator to his village, Haocha, or Kucapungane, in the central mountains of Southern Taiwan. In Xiong's home, the narrator sees three framed portrait photographs.

The first one is of a Japanese soldier.

The second one is of a Communist soldier.

The third one is of a Nationalist soldier.

These portraits are, respectively, of Xiong's uncle, or, to be accurate, the first husband of his mother, his father, and his older brother. His uncle, the Japanese soldier, died in combat in the Pacific War in Taiwan, which back then was under Japanese rule. Xiong's father was among the soldiers in the Communist Party sent to fight in Mainland China after Taiwan was liberated from Japanese rule, but disappeared completely. His elder brother, a soldier in the Nationalist army led by Chiang Kai-shek, died for the Republic of China.

"If there is a photograph of a Japanese, Communist, and Nationalist soldiers lined up, that would certainly make a tumultuous noise." Xiong spoke casually.

"Has it ever occurred to you that these people are your family?" I asked him seriously.

"Well yes. Many people in the mountain district are like us." He spoke flatly, just as before.

"Doesn't it make you upset?"

"Upset...?"

"Make you sad and angry..."

What I said made him think. After a few moments, I questioned him again:

"Don't you feel sad and angry?"

"Angry? At whom?"

(Huang Chunming Zhànshì Gānbēi!, translated by the Japan Foundation from Banana Bōto: Taiwan Bungaku e no Shōtai [Banana Boat: An Invitation to Taiwanese Literature], JICC Publishing)

As I was reading, I tried to imagine what the original Chinese text for Xiong's question "At whom?" was. I immediately corrected myself, however, remembering that the mother tongue of Xiong, a character in this short story written in Chinese, is not in fact the Chinese in which he fluently converses with the narrator of the story, but the language spoken by the Rukai people. Moreover, the fact that Xiong's mother tongue is not Chinese, the national language of Taiwan, does not make him a "foreigner." On the contrary, his predecessors have been living in Taiwan much longer than the predecessors of the narrator, who is Han Chinese.

In the historical background of the story, the aboriginal people of Taiwan are caught between the clashing ulterior motives of two nations, and, as a result, four generations of men from the same family and the same community are forced to adopt different nationalities and fight as soldiers for different countries in order to protect their people as well.

Whether or not I faced the wall, the soldier figures from different generations continued to appear before my eyes. Just before my will succumbed to the influence of the alcohol, those figures seemed to be prominent. Facing the wall lined with the photographs, I was still able to pick up the wine glass, empty but for a few drops, and silently repeat:

"To the soldiers!"

(Huang Chunming Zhànshì Gānbēi!, translated by the Japan Foundation from Banana Bōto: Taiwan Bungaku e no Shōtai, JICC Publishing)

When I first read this story translated into Japanese by Sakujiro Shimomura, I felt dizzy. It brought into sharp focus the complex fissures that tear apart the multidimensional Taiwanese society, and at the same time, it stunned me with the incredible talent of Huang Chunming who managed to compress this overwhelming content in only 32 pages of 400-character manuscript paper.

In 1945, after Japan's defeat in World War II, Taiwan was restored to the fatherland. In Chinese this event is called "guāngfù" ("retrocession" in English). The passion that fills up this expression perhaps, in a way, reverses the pent-up resentment accumulated over the 50-year rule of Japanese imperialism. As a result of these events, for the first time in half a century, Taiwan restored its connections with Mainland China, but the fatherland to which it was returned was in the height of a severe conflict between the Communist Party and the Nationalist Party. By 1949, the Nationalist Party were defeated on the mainland by the Communist Party and retreated to Taiwan, where they formed a government and again Taiwan seceded from Mainland China. This means that for almost 100 years, from 1895 to the present day, free travel between Taiwan and Mainland China was possible only for few short years. As a result of these political events, Taiwan, a lonely tropical island, began its unique postwar development.

(Excerpt from the Preface of Banana Bōto: Taiwan Bungaku e no Shōtai, translated by the Japan Foundation)

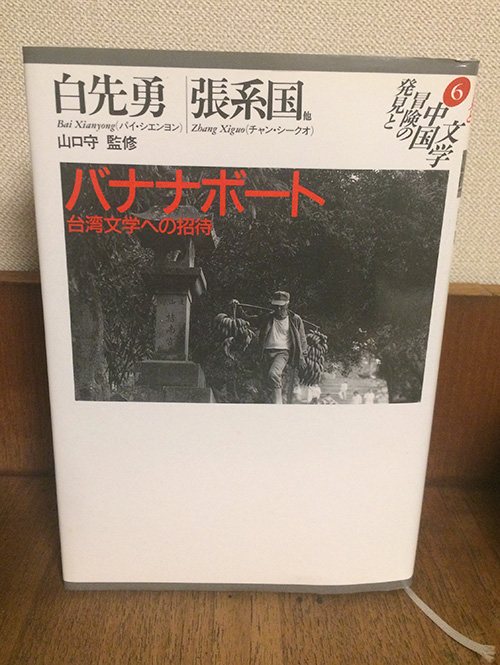

This text, written by Mamoru Yamaguchi, is a quotation from the preface of Banana Bōto: Taiwan Bungaku e no Shōtai (JICC Publishing), which contains the Japanese translation of Zhànshì Gānbēi!.

Banana Bōto: Taiwan Bungaku e no Shōtai is the sixth installment of the series Hakken to Bōken no Chūgoku Bungaku [Chinese Literature: Discovery and Adventure], and, as suggested by its subtitle, presents a fine selection of Taiwanese literature works.

http://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/4796601775

This book is a collection of works by Taiwanese authors, which are filled with anguish and pain, and yet are shining as beacons of hope. They have been carefully selected by translators and editors inspired by a desire to present the best examples of Taiwanese literature to Japanese readers, so all of them are well-written and fascinating.

As for me, thanks to my long-lasting and stubborn determination to avoid Taiwanese literature, now I have plenty of works to read and enjoy.

Today, I, a Japanophone Taiwanese, stopped being so stubborn and diligently read the Japanese translations of Taiwanese literature.

Right: Huang Chunming's masterpiece Sayonara, Zàijiàn [Sayonara, Goodbye] (published by Mekong Publishing, distributed by Bunyusha).

Left: the original Traditional Chinese edition that I bought in a bookstore in Taipei. It is a bestseller in Taiwan.

Follow Wen Yuju on Twitter https://twitter.com/wenyuju

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…