3. I Live in "Japanese"

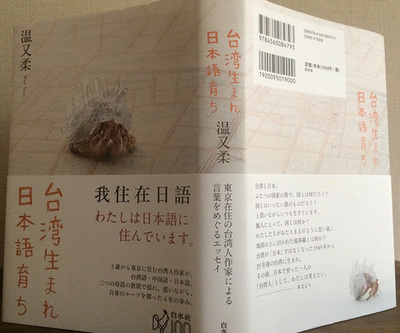

My first collection of essays, Taiwan umare Nihongo sodachi (Born in Taiwan, raised in Japanese) was published at the end of last year. The catchphrase on the belly band of the book, "Wǒzhùzàirìyǔ. I live in Japanese," was put there by the editor.

When my book Raifuku no Ie was translated and published in Taiwan, I was asked the following question in Chinese. "As a person who grew up between Japan and Taiwan, of which do you think as your home?" My immediate and spontaneous response was "Wǒzhùzàirìyǔ,"which means "I live in Japanese."

I live in Japanese.

It was a seldom heard and slightly bizarre expression, but I clearly remember that the moment it came out of my mouth, it felt just perfect.

Not "in Japan," not "in Taiwan," but "in Japanese (language)."

I was not born as a Japanese person and do not hold Japanese nationality. Yet, I grew up surrounded with the Japanese language. I live in a place where Japanese language is spoken.

I was born as a Taiwanese, and hold a Taiwanese passport, but I rely mostly on the Japanese language for my internal monologue.

Even now, when I am in Taiwan, I sometimes fall under the illusion that the Japanese language is something that belongs only to me. There are many Japanese people in Taiwan, of course, as well as many Taiwanese people who speak Japanese. Yet - and this was particularly true for my childhood - after staying in Taiwan for a while, amidst the sounds of Chinese and Taiwanese, I would get the feeling that the Japanese language had taken refuge in my heart where it was reverberating quietly.

That is why I get a start when I hear people speaking in Japanese at Narita Airport or Haneda Airport. The presence of Japanese people around me, and the ambience created by the language they speak, give me the feeling that I have returned to my routine life in the realm of the Japanese language.

"Wǒzhùzàirìyǔ. I live in Japanese."

This is what I said, but in fact the Japanese that I know is quite limited.

I came to this realization at some point in my life.

I grew up in Tokyo, so I can speak only Tokyo dialect.

But, of course, Tokyo is just one small part of Japan.

The language spoken in Tokyo--also known as "standard Japanese"--is not the only version of Japanese.

I was claiming that "I live in Japanese," so I felt the need to learn more about the dialects spoken in the past and the present in various regions of Japan.

This February, just as this desire of mine deepened, I got a great opportunity to realize it. I received a request from theatre director Akira Takayama to write a short story based in Akita Prefecture.

Mr. Takayama, as the leader of a theater unit Port B, has created numerous outstanding theatrical productions characterized by the involvement of the audience using methods that expand the equation "play = audience" to actual cities and society based on the concept of "spectatorship."

Port Tourism Research Center, an artistic collective founded and led by Mr. Takayama, is currently implementing a project called "Media Performance," which discovers new potential in local communities through collaborations between art and local media. In fiscal year 2015, the project advanced research activities based in Akita under the theme "Language and Education."

One early morning in the midst of winter, I set off for Akita on a shinkansen bullet train together with Port Tourism Research Center Director Tatsuki Hayashi. We reached our destination around noon. With the cold wind on my face, I raised my eyes to the sky. Snowflakes danced in the sunlight streaming through the clouds. I had seen sunshowers before, but that was my first experience of a "sun snow," and I felt very excited.

Our first stop was the former village of Nishinaruse (today part of Yokote City), where we visited the museum dedicated to Kumakichi Endo, a teacher who passionately taught standard language education to the children of Akita.

Before the war, the village of Nishinaruse in Akita Prefecture was known as the "Standard Language Village." Today, the Masuda Town Municipal Nishinaruse Elementary School is no longer operated, but offers visitors an exhibit of materials related to Kumakichi Endo.

Next, we visited the Higashinaruse Elementary School and attended English and Japanese language classes. I was greatly impressed by the way children, who use the local dialect when speaking with elderly people at home, study both standard Japanese and English as new languages in a fresh and lively manner.

This short day trip turned into an unforgettable experience for me. Until then, I used to consider the Japanese language only in terms of the juxtaposition of Japan-Taiwan, but this encounter with the history of standard language education conducted in that snow-covered village and the interaction with the children of Akita greatly expanded my image of the Japanese language.

"What language did you speak at home as a child?" "In my home, we spoke in Taiwanese and Chinese." I truly enjoyed chatting with the children I met in Akita.

In the end of February, I completed a short story titled Otenki yuki (Sun snow).

The short story will be published in full in the overall project document created by the Port Tourism Research Center, so I will post information later for those who are interested in reading it.

Just by thinking of the varieties of the Japanese language spoken in different regions of Japan, I intuitively knew that "Japanese" as my place of residence was a much more abundant place than I had imagined it, and my visit to Akita confirmed that knowledge. The joy of this discovery has sparked in me an ever growing desire to experience in a more specific manner the richness of the Japanese language. I wonder where I should go next.

Wen Yuju

Wen Yuju

Author Wen Yuju was born in 1980 in Taipei, Taiwan and moved to Japan with her Taiwanese parents before she turned three. In 2006, she completed the Master's Program of the Graduate School of Intercultural Communication at Hosei University. In 2009, she won the Subaru Prize for Literature with Kokyokoraika. As a Taiwanese person who writes in Japanese, in her creative work she explores the themes of language and identity. Her works include Raifuku no Ie (2011, Shueisha), and Tatta Hitotsu no Watashi no mono dewa nai Namae (2012, Happa-no-Kofu; for Kindle). In 2014, she formed a duo with musician Keitaney-Love Kojima, and launched a series of collaborative performances under the title "mapo de ponto--Kotoba to Oto no Ofukushokan [Correspondence of Words and Sound]," featuring Wen's reading and Kojima's music. Her most recent work is Taiwan umare Nhongo sodachi (2015, Hakusuisha), a collection of essays born from her experience as a Taiwanese person raised in Japan. She appears in Homeland in the Borderland, a documentary film directed by Keiko Okawa, which follows author Hideo Levy as he returns to Taichung, Taiwan, for the first time in 52 years.

![]()

Follow Wen Yuju on Twitter: https://twitter.com/wenyuju

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…