003 To Russia with (Invisible) Waves

Prabda Yoon

Writer and publisher

I have to admit, when I feel an immediate eagerness to accept an invitation from abroad to participate in an event (usually related to film or literature), that enthusiasm is often triggered not by the premise of the event itself but more by the traveler's--perhaps even nomadic--spirit in me. I'm always secretly hoping to get email from "exotic" places like Egypt, Cuba, Morocco, Mongolia, etc., asking whether I would like to attend some kind of festival in their territories. I know people who are quick to brush off events that aren't "influential," not the creme de la creme in their fields, places that don't "do" anything to advance their career, and I understand the logic perfectly, but perhaps because I'm a writer, new places, wherever they may be, mean new people and new experiences (not to mention new bookshops!), and always benefit me in some ways.

My first screenplay for Thai director Pen-ek Ratanaruang, Last Life in the Universe (2003), brought me some recognition among Asian film enthusiasts and it was really my one ticket to the international film community. Most of the invitations from film festivals I've received from abroad so far have been because of that work. But I also wrote another screenplay for Pen-ek, the lesser known Invisible Waves, and as far as writing experiences go, I'd have to say that writing Invisible Waves was probably one of my most adventurous (not counting the experiences I had writing a couple of other movie screenplays that turned out to be truly invisible). I worked on the first draft of it closely with Pen-ek and the cinematographer, Christopher Doyle, for several months. I went on a short cruise in the south of Thailand to find out what it was like to be on a cruise ship (part of the story takes place on a cruise). We went on a location scouting trip together in Phuket. I went to stay in Hong Kong for a month to finish it (the story takes place in Hong Kong and Phuket). For many reasons, the film was almost never made, but, after almost two years of negotiations and several script revisions, it was eventually completed and premiered at the Bangkok Film Festival in 2006. For everyone involved, it felt like the end of a very long journey.

To be honest, I didn't expect to be invited to any film festival because of "Invisible Waves". The general reception of it was much colder than the reception of "Last Life". Furthermore, by that time I had already gathered I didn't quite belong in the film industry, and the level of my attraction to film festivals had dropped almost to zero. Then one day I received that email, the email I was always secretly hoping for; the sender asked whether I would attend the international film festival in Vladivostok for a Q & A session following the screening of "Invisible Waves". I couldn't believe it. I probably started to pack my suitcase even before I replied.

I knew next to nothing of Vladivostok at the time. So when I learned that it was a Russian port city on the Pacific Ocean, near China and North Korea, my excitement escalated. I'd never been to Russia before, but the word "Russia" was always in my life for a couple of unrelated reasons. My given name, though perfectly Thai sounding (but meaningless in itself), was inspired by the Russian newspaper, PRAVDA, which means "truth." In my teens, I discovered the graphic works of Russian avant garde artists such as El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko, which impressed me so profoundly that I decided to major in graphic design in college. When I eventually transferred to study fine arts, one of my "heroes" in painting and sculpture was the Russian Suprematist, Kazimir Malevich. In literature, the two big names that continue to influence my writing, in different ways, are Russian: Leo Tolstoy and Vladimir Nabokov. Then, of course, there's the Russian cinema. The visual innovations and lyricisms executed by cinematic pioneers Dziga Vertov and Andrei Tarkovsky taught me that it was possible to write poetry with the movie camera.

Yet Russia itself always seemed to me a very distant place. Why would I ever go there? Now with the invitation from Vladivostok I had a reason, thanks to "Invisible Waves".

However, with hindsight, being in Vladivostok was more like getting closer to Russia than being really in Russia. It was still summertime when I arrived, so the weather was very familiar to an Asian visitor: sunny, hot and humid. I was there for about a week, and occasionally the city would suddenly get hit by a heavy rain storm, just like in Thailand. Most of the locals looked "Russian" enough, with their blonde hair and blue eyes, yet everything else felt very Far East. Nonetheless, the traveler in me enjoyed it all.

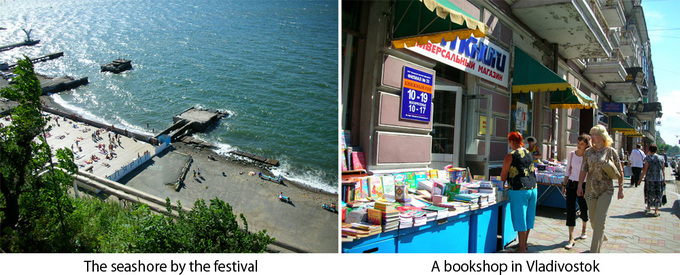

The cinema complex OCEAN where the festival took place

The festival itself was a big event for the residents of Vladivostok, who flocked to the film screenings with great enthusiasm. Many of the people working for the festival were student volunteers, who were more than excited to meet filmmakers and actors from around the world. The ones I had the chance to converse with were surprisingly knowledgable about contemporary world cinema; they certainly knew more about it than me, and that was something rather refreshing in comparison to big, well-known film festivals, where every conversation would be more about business than the art of filmmaking.

When I had free time I would sneak out of the festival (which took place mostly at the city's biggest movie complex near the seashore) to explore the town. There were, not surprisingly, many monuments and murals done in the Socialist style, which I appreciated. I was able to buy all the Russian souvenirs I could ever want. (Yes, of course, like any good tourist, I bought a couple of matryoshka dolls to take home with me.)

Before the screening of "Invisible Waves", which was towards the end of my stay in Vladivostok, I was introduced by the festival organizers to a woman who, they said, was the wife of a successful local businessman. At first I didn't understand why she seemed so happy to meet me. "You're the writer of 'Invisible Waves', right?" She asked excitedly. I said that I was. "You went on a cruise ship in the south of Thailand to research for the script, didn't you?" I said yes. In fact, the very ship I went on was also used in the movie. The woman then told me, "My husband bought that ship. We turned it into a restaurant." I was completely stunned.

Apparently, without knowing anything about "Invisible Waves", the Vladivostok entrepreneur couple saw the ship in Thailand and decided to buy it. They only learned about the movie later, probably from the previous owner, and wanted to see their boat on the big screen when they were informed that it was being shown in the festival in their own city. The most unbelievable part of the story, for me at least, was that the ship was now in Vladivostok, not in Thailand! It was docked in the sea, not too far from where I was staying.

Even though I didn't pay a visit to the ship, the whole notion was quite surreal, and it made my trip to Vladivostok feel even more "exotic." The ship I went on in Thailand more than two years earlier to research for a movie ended up in the movie itself, then traveled to a Russian city I'd never heard of, until I was invited to it because that same movie was being screened in its film festival. Invisible waves indeed!

Prabda Yoon

Prabda Yoon

Born in 1973, a Thai writer and publisher based in Bangkok. He has published numerous novels, short story collections, and essay collections. In addition, he has also translated modern English-language classic literature such as The Catcher in the Rye and A Clockwork Orange into Thai. In 2002, his short story collection, Kwam Na Ja Pen (English: Probability), won the SEA Write Award.

Apart from working in Thailand, Prabda has regularly written for Japanese magazines and exhibited artworks in Japan. He has written 2 screenplays for films starring Tadanobu Asano and he is presently collaborating on various art projects with Japanese contemporary artist Kohei Nawa. His literary works have been translated into Japanese, of which the most recent is the novel Panda.

Keywords

- Literature

- Film

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- Transboundary/Study Abroad/Travel

- Thailand

- Russia

- film festival

- Pen-ek Ratanaruang

- Christopher Doyle

- Phuket

- Bangkok Film Festival

- Vladivostok

- PRAVDA

- El Lissitzky

- Alexander Rodchenko

- graphic design

- Kazimir Malevich

- Leo Tolstoy

- Vladimir Nabokov

- Dziga Vertov

- Andrei Tarkovsky

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…