001 Sandwich: Unfinished Space Between Teaching and Learning

Prabda Yoon

Writer and publisher

Can art be taught? I used to believe not, but now I think I might have regarded the question from too narrow a perspective. Worse, I probably regarded the meaning of "art" too narrowly as well. If teaching art means to show someone a guaranteed way of becoming a successful, respected, famous, or even interesting, artist, then my initial hunch may have not missed the mark by much. But art is, or should be understood as, more than just occupational tool. At its most valuable, essential level, art is a way of looking at, indeed of embracing, life.

Regardless of what life is, we know that we can live or look at life with numerous attitudes. Living or looking at the world artistically is one attitude, and one which, I now think, can be learned and approached more effectively, rewardingly, through creative and generous teaching.

I went to art school, and I felt a peculiar melancholy in being an art student. Everyone knows that not all art students will become professional artists, and everyone knows that those who do will struggle. After 6 years of art education, I still didn't see how art would inhabit my life, how it would lead me to an "artistic" landscape. The tunnel to the so-called art world seemed too hopelessly dark. But I was sure of at least one thing: living without art was unthinkable. At that point I wished I had been shown not just how to make certain kinds of art but also the way to seamlessly weave art into my life, a life that might not, despite my choice of education, have anything to do with "Art" at all.

When I first met Nawa Kohei, in the winter of 2004, I think he had not yet started to teach at the Kyoto University of Art and Design (KUAD). Frankly, I couldn't really see him as a teacher. Young, determined, and clearly on the rise in Japan's Contemporary Art world, his profile just didn't fit someone who would take up a teaching job, at least not that early in his career. So I was surprised, naturally, when I visited him at his first studio in Osaka a few years later, to learn that he was now, only in his early thirties, Nawa-sensei to aspiring young artists.

When I first met Nawa Kohei, in the winter of 2004, I think he had not yet started to teach at the Kyoto University of Art and Design (KUAD). Frankly, I couldn't really see him as a teacher. Young, determined, and clearly on the rise in Japan's Contemporary Art world, his profile just didn't fit someone who would take up a teaching job, at least not that early in his career. So I was surprised, naturally, when I visited him at his first studio in Osaka a few years later, to learn that he was now, only in his early thirties, Nawa-sensei to aspiring young artists.

Not long after that, Nawa told me he was moving to a new studio, a place by the Uji river in southern Kyoto. He kept mentioning the word "sandwich" in our conversation and I didn't understand why. Was he hungry? Was he making some kind of joke only the Japanese would get? Now well-established (perhaps most famously as the sole location in a music video for a song by the popular pop duo Yuzu), Sandwich is of course the name of Nawa's new studio, a two-story building converted from a local sandwich manufacturing factory. I saw Nawa's Sandwich almost from its beginning, when the interior was shockingly bare and a touch dangerous to walk in. Nawa informed me that this was not meant to function only as his personal studio; Sandwich would be a creative platform "for anyone who wishes to use it."

I was rather skeptical of his ambition until I returned to Sandwich in 2009, when Nawa and I collaborated on a short film. The film, entitled "The King" after the nickname of its actor (and Sandwich's technical wizard) Fujisaki Ryoichi, was shot entirely at Sandwich by a small crew, composed mostly of Nawa's students and assistants. It was our first artistic collaboration and the result is still far from finished, but I did feel that Sandwich itself was successful in bringing together individuals of different artistic skills, tastes, and temperaments. The unusual, indefinitely under construction space somehow helped to create an inspiring atmosphere, keeping the crew encouraged and optimistic, even during the midst of a brutal winter with little heating.

I was rather skeptical of his ambition until I returned to Sandwich in 2009, when Nawa and I collaborated on a short film. The film, entitled "The King" after the nickname of its actor (and Sandwich's technical wizard) Fujisaki Ryoichi, was shot entirely at Sandwich by a small crew, composed mostly of Nawa's students and assistants. It was our first artistic collaboration and the result is still far from finished, but I did feel that Sandwich itself was successful in bringing together individuals of different artistic skills, tastes, and temperaments. The unusual, indefinitely under construction space somehow helped to create an inspiring atmosphere, keeping the crew encouraged and optimistic, even during the midst of a brutal winter with little heating.

I never really saw Nawa in action as a teacher until this past August, during my one-month residency in Kyoto. Nawa-sensei brought his special class (called Ultra Factory) to Sandwich for a drawing workshop that lasted throughout the week of my visit. The students, a mixture in age and academic levels, were to share large sheets of paper and draw together until they felt the drawings were finished. Nawa-sensei invited me to join and to supervise the workshop, even though I knew only a few words of Japanese. I was nervous and self-conscious at first, but the enthusiasm of the students, their surprising eagerness to learn, helped me to relax, and I was eventually able to try to express my thoughts to them, in English. And I could tell they really wanted to understand me.

Nawa-sensei is a patient and unconventional teacher. He lets his students explore freely on their own several times before sharing his opinions and guiding them with his own sensibility. He doesn't teach drawing by talking about drawing. Instead, he will sometimes ask the students to listen and draw the sounds they hear. He draws with them and lets the silence in his lines tell them what he means.

At the end of the Sandwich workshop the students asked me something I hadn't anticipated: "How do we know when a drawing is finished?" Like all truly good questions, to this there is also no true answer. However, to say, "I don't know" or "there is no way to know" to a group of students genuinely waiting for a useful reply seemed irresponsible and cruel. So I tried to give a technical answer, something about composition, texture, empty space, balance, juxtaposition, etc. Probably the same sort of jargon I used to get from my teachers years ago. Strangely, this awkward and difficult moment made me feel the joy of teaching art. I found it inspiring, and highly challenging, to come up with a practical way to show "when a drawing is finished," knowing that it's perhaps an impossibility.

But that's the point, or should be, if you're, like me, the sort of person who feels that life without art is unthinkable, even if you don't live in the "art world." You have to learn to look at life as a drawing that constantly forces you to ask yourself when it's finished, knowing that the answer is infinitely ambiguous. The fun part is how you juggle that ambiguity. That's learning art.

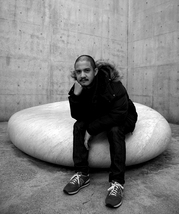

Photo by Sandwich Team

Prabda Yoon

Prabda Yoon

Born in 1973, a Thai writer and publisher based in Bangkok. He has published numerous novels, short story collections, and essay collections. In addition, he has also translated modern English-language classic literature such as The Catcher in the Rye and A Clockwork Orange into Thai. In 2002, his short story collection, Kwam Na Ja Pen (English: Probability), won the SEA Write Award.

Apart from working in Thailand, Prabda has regularly written for Japanese magazines and exhibited artworks in Japan. He has written 2 screenplays for films starring Tadanobu Asano and he is presently collaborating on various art projects with Japanese contemporary artist Kohei Nawa. His literary works have been translated into Japanese, of which the most recent is the novel Panda.

Back Issues

- 2022.7.27 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2022.6.20 Beyond Disasters - T…

- 2021.6. 7 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.28 Crossing Borders, En…

- 2021.4.27 Contributed Article …

- 2021.4.20 Contributed Article …

- 2021.3.29 Contributed Article …

- 2020.12.22 Interview with the R…

- 2020.12.21 Interview with the R…

- 2020.11.13 Interview with the R…