Youth Drama Workshop in Aceh, Indonesia―A Source of Strength

Masanori Takaguchi

Asia and Oceania Section

Japanese Studies and Intellectual Exchange Dept.

The Japan Foundation

Last day of the workshop (Day 8): students at the farewell party look at pictures taken during the project.

Last day of the workshop (Day 8): students at the farewell party look at pictures taken during the project.

In March 2011, I was one of the many people who watched the television in stunned disbelief as the tsunami swallowed up the east coast of the Tohoku region of Japan. Three months before the disaster, in December 2010, I had been surrounded by the cheerful smiling faces of teenagers in the city of Banda Aceh on the northern tip of Sumatra Island, Indonesia. While I did not fully realize its impact at that time, six years earlier the Aceh region had also fallen victim to a tsunami generated by the Indian Ocean earthquake in December 2004. Countless lives had been lost. The tsunami that struck the region, already battered by some 30 years of separatist armed conflict, brought significant consequences. The peace agreement that was signed the following year has been largely attributed to the disaster.

What sent me to Aceh in 2010 was a project called the Youth Drama Workshop in Aceh, Indonesia. The project involved holding a camp-type theater workshop for young people in their teens from various parts of Aceh Province who had been affected by the war. It was launched with two objectives. The first was to help the younger generation learn to cooperate, using theater as a medium of expression, so that they would be able to work together to build the future of Aceh regardless of whether they had supported the separatist movement or the national government in the past. The second objective was to assist peace-building efforts in the region through the Japan Foundation's cultural exchange programs.

Day 2: Students playing traditional musical instruments

Day 2: Students playing traditional musical instruments

Day 2: Song and dance performance

Day 2: Song and dance performance

The first round of workshops took place in 2007 in collaboration with local NGO Komunitas Tikar Pandan. A total of thirty youngsters took part, with ten teenagers selected from each of the three areas that had been under the influence of either the former separatist group or the former government forces. In the following year, those participants got together again in the follow-up program called Aceh Youths Conference 2008. Then a second round of workshops was held from December 5 through December 12, 2010, inviting a whole new group of participants. I will not go into detail here about the 2007 and 2008 programs, which are described in Japanese at the websites below. I was assigned to work on this project for the first time in 2010, and to be honest, I did not know what to expect of it even as I busied myself preparing for the workshop.

"Creating a theater workshop with the youths of Aceh"--Project background, implementation and the future outlook (2007)

"Aceh Youths Conference 2008"

If what I had been feeling before my departure to Aceh was something close to anxiety, it was quickly blown away by the participants--the thirty energetic middle and high school students, and the six previous workshop participants who came on board to assist us, as well as the local college students who were involved in the plays and recitations. As in 2007, we had asked the theater education specialists Setsu Hanasaki and Kota Suzuki to lead the sessions as the workshop facilitators.

At the beginning of the sessions the facilitators organized a variety of icebreaker games and activities to help ease the tension among the students, who were meeting each other for the first time. Everyone enjoyed playing various games involving physical activities; for example, the participants were put into small groups and asked to create and then present a self-introduction poster, and they sang songs while sitting down in a circle and moving only their upper bodies. It was delightful to watch them having fun and getting to know each other at the same time through a variety of activities provided by the facilitators.

Left: Day 2: A bird-cage game, similar to the game of musical chairs

Left: Day 2: A bird-cage game, similar to the game of musical chairs

Right: Day 2: Students try to create a shape while holding hands, without breaking the circle.

As the session went on, the junior facilitators--this was the title given to the previous workshop participants and the local college students--started taking charge and stealing the spotlight from the younger participants, who were supposed to be the main subjects of the workshop. This may have been because the older kids were familiar with the program format of Hanasaki and Suzuki. Realizing the situation, Agus Nur Amal, another workshop facilitator, gathered the junior facilitators for a talk during a break after lunch. Agus is a traditional Acehnese story-teller performing across the country, and he was assisting with the workshop as a local specialist. He advised them that their job as junior facilitators was strictly to support the younger participants, for example, lightening up the mood or giving encouragement and tips when necessary, and that they should not show off and try to grab all the attention.

Agus's little talk had a remarkable effect; from then onwards the junior facilitators stuck to their supporting roles and became highly reliable assistants. I noticed that the staff who had known them from the previous workshop--Hanazaki and Suzuki, who were so happy to see them again, the interpreter Urara Numazawa, Mariko Mugitani of the Japan Foundation, Jakarta--all appeared thrilled to witness how mature and responsible they had become. Our young assistants were very patient and helpful; there were instances where they would hold back the urge to jump in, and instead stand back and let the students work things out for themselves, or they would happily volunteer to lend a hand to the senior facilitators. I met them for the first time in this program, and was sincerely impressed by their behavior.

Day 3: Students try to depict a flower using their bodies.

Day 3: Students try to depict a flower using their bodies.

Day 3: Students try to physically depict a scene where a teacher is writing on the black board and a student is studying at a desk.

Day 3: Students try to physically depict a scene where a teacher is writing on the black board and a student is studying at a desk.

Day 3: Students express grief using their bodies.

Day 3: Students express grief using their bodies.

Day 4: The students really loved to sing. Groups would start singing outdoors whenever they had a break or some free time.

Day 4: The students really loved to sing. Groups would start singing outdoors whenever they had a break or some free time.

Midway through the eight-day workshop, we took the students on a field trip that included a visit to a newspaper office and the live studio of a television station. The students also attended a seminar on social issues facing Aceh hosted by Komunitas Tikar Pandan. They conducted interviews on the college campus where the workshop was being held, and, under the direction of the video producer Shu Iijima, created wall newspapers using the information they had gathered in the interview. The broad range of activities was designed to stimulate the young people's curiosity and to help broaden their perspectives. In conjunction with these activities, the students worked on theater skills in the workshop, and gradually developed the capacity to describe events and express their emotions.

Day 4: Students conduct interviews on the college campus.

Day 4: Students conduct interviews on the college campus.

Midway through the workshop, the students started to work on the short play that they were going to produce and perform on the final day. First they had to select a topic related to the pressing question of how to go about building the future of Aceh, and then write the script. In performing these tasks the students needed to squarely face up to Aceh's current problems as well as its past.

The students would not be able to sidestep memories of the conflict in the process of putting together the play. Scenes of fighting were described in vivid detail in the essays written by the 2007 workshop participants. This being a very sensitive issue, the facilitators kept a close watch on the students so as to detect the slightest change in the atmosphere of the classroom. I could feel myself becoming tense, too, seeing their focused attention and the interpreter's cautious demeanor.

In one of the workshop activities, one student would play the part of a sculptor. Pretending the other students were lumps of clay, the sculptor would talk about things he had seen or heard during the conflict. Using this approach, the participants recounted their wartime experiences. What they described left me speechless. I have never experienced a war but the students' stories terrified me. Then in the midst of these dreadful accounts someone started crying. It was not one of the teenage participants but a college student who was one of the calmest and most mature of the junior facilitators. Later she explained to us how she had felt, saying that it broke her heart to imagine how scared and sad the participants must have been, since they clearly remembered those horrible experiences despite having been so young when it all happened.

Day 6: What are the issues confronting Aceh? The students brainstorm topics for the play.

Day 6: What are the issues confronting Aceh? The students brainstorm topics for the play.

The students went through several such activities in the remaining time of the workshop. Then they were divided into four groups. Each group selected a theme, drafted a short script and performed the play on the last day of the workshop. The titles of the plays were: Everyday Life of a Village; The Tragedy of a Family with Step Children; Conflict; and Saying No to Drugs. In the words of the facilitators, these plays were not supposed to be directed by a director, but were meant to be created spontaneously by the actors themselves. While there was some input from the junior facilitators, it is fair to say in all four pieces the young people succeeded in demonstrating their enormous expressive abilities and creativity. On the eve of the last day of the workshop, we rented the stage of a radio station where the students performed their plays. They received generous applause from the audience of some 200 people who filled the hall.

Day 6: Students select a topic for the play while a junior facilitator moderates their discussion.

Day 6: Students select a topic for the play while a junior facilitator moderates their discussion.

Day 6: Rehearsing the play Everyday Life of a Village

Day 6: Rehearsing the play Everyday Life of a Village

Day 6: Students listen intently to professional feedback after the rehearsal.

Day 6: Students listen intently to professional feedback after the rehearsal.

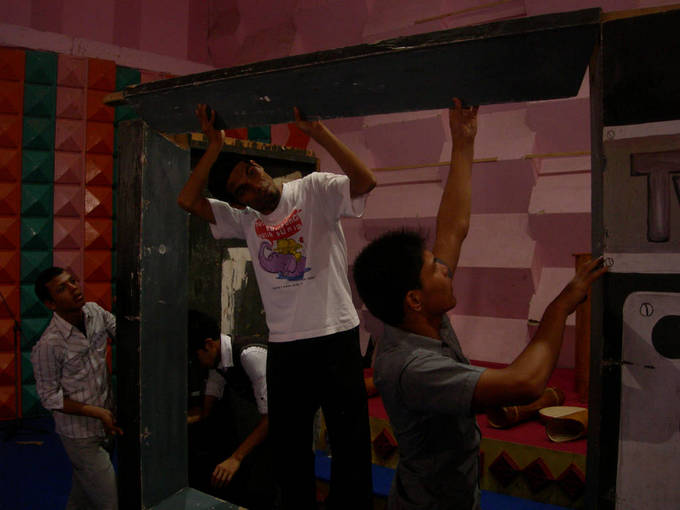

Day 7: NGO staff and junior facilitators prepare the stage.

Day 7: NGO staff and junior facilitators prepare the stage.

Day 7: Students rehearse on the real stage.

Day 7: Students rehearse on the real stage.

Day 7: The day of the performance. The students sing a song before the plays.

Day 7: The day of the performance. The students sing a song before the plays.

After the project was completed, I saw the students off to their homes and said good-bye to the junior facilitators. Then in the short time I had left before leaving Aceh I visited the site where a huge tanker had been washed up by the tsunami. It was about two kilometers inland from the coast. The imposing ship that will never sail again sat there as a monument, a silent testament to the staggering scale of the tsunami.

One of the short plays performed by the students, The Tragedy of a Family with Step Children, contained plotlines and staging that were clearly influenced by soap operas on television, such as a character being deceived by her new partner, or a child becoming a delinquent. Yet one could argue that such episodes of sad family life, while they may appear melodramatic, are in fact a reflection of actual problems seen frequently in Aceh, where a huge number of families lost loved ones in the tsunami.

Ever since the earthquake and tsunami struck the Tohoku region of Japan, Aceh has been constantly on my mind. Since the March 11 disasters, city streets and television airwaves have been filled with public advertisements and slogans intended to promote recovery. Some of them are inspiring while others I am not sure about. Whatever the impact, the ads force me to stop and think about what it really means, at this very challenging time, to be engaged in work that aims to foster international friendship and build support for Japan around the world. Whenever I confront myself with the question of how much and what sort of difference my work can make, I realize how little power I have. Nevertheless, there are experiences that have given me courage; my experience in Aceh is one of those. That encouragement came from the sparkling smiles of the workshop participants and the young people who helped us run the program as junior facilitators; their smiles signified that Aceh was well on its way to recovery from the devastation inflicted by the bloody war and the catastrophic natural disaster.

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2024.3. 4 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.10 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.3.28 JF's Initiatives for…

- 2023.1.27 Living Together with…

- 2022.11.16 Inner Diversity <…

- 2022.6.21 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.3.22 JF's Initiatives for…

- 2022.3.14 JF's Initiatives for…

- 2022.2.14 JF's Initiatives for…

- 2022.2. 4 JF's Initiatives for…