Unraveling the Makers and Meanings of Japanese Buddhist Embroideries

Carolyn Wargula (PhD Candidate, University of Pittsburgh)

The Japan Foundation invites academics and researchers in the area of Japanese studies to study in Japan. The guest contributor for this issue is Carolyn Wargula, a 2018 Japanese Studies Fellow who researched "Embodying the Buddha: The Presence of Women in Japanese Buddhist Hair Embroideries, 1200-1700" at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies as a fellow writing her doctoral thesis.

Exterior of Taimadera Okunoin Temple

Every time I have come here, there seem to be few visitors, only the empty staircase, the silent Mandara Hall with an elegant tapestry, the gardens filled with the finest peonies in Japan. It gives the illusion that I have discovered this place, that it is my secret, despite the temple's 1400-year-old history. A monk in black robes approaches to greet me as I pass through the main gate onto the pale gravel grounds of Taimadera. This temple's wooden halls with wide projecting eaves contain the treasures of a vanished golden age, when crowds of pilgrims gathered to see the lavish textiles said to be woven and spun by the legendary Chūjōhime. It is here in the countryside of Nara that I have come to view these medieval embroideries safely ensconced in a vitrine, their once vividly-colored threads now faded to a dull brown.

At first glance, it may seem glamorous to conduct research on these forgotten textiles, but most of the work actually involves sitting hunched over in the library, identifying the faded characters inscribed on the back of these embroideries, and then carefully transcribing them into modern Japanese and English. I have been studying Japanese Buddhist embroideries as a PhD student for almost 5 years now, yet I have struggled to put my finger on precisely what captivates me about this topic. While a bit embarrassing to admit as an art historian, the appeal of these textiles for me has never been purely or even primarily the visual. These artworks are deeply personal and simultaneously universal, offering an intimate view of religious experience in ancient and medieval Japan.

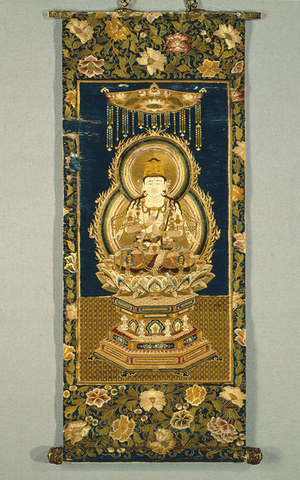

Important Cultural Property

Embroidery of Dainichi Nyorai (Mahavairocana)

13th century

Hosomi Museum

For the better part of 200 years, roughly between 600 and 800, monumental embroidered Buddhist images, some over 10 meters tall, were commissioned by the imperial court. It is hard to believe that these valuable pieces once existed since most of them, including a massive pair that were once hung within the Great Buddha Hall of Tōdaiji, no longer survive. Over the coming centuries, all kinds of Buddhist images were embroidered—the Descent of Amida and Bodhisattvas, which represent the Buddha and his retinue welcoming the souls of believers into the Western Paradise, being the most popular.

Buddhist embroideries are primarily about death. They were usually commissioned by women for a loved one's memorial service and often incorporate her hair to depict the most sacred parts. Kamakura- and Muromachi-period women stitched their hair into an embroidery to reenact a performance of bodily sacrifice and transformed the female hair, a frequently aestheticized material, into sacred matter suitable for depicting the divine.

I never encountered the word shūbutsu (Buddhist embroidery)—like most people in Japan—during my 14 years of living there. That changed in 2015 when I stumbled upon a single image of a Buddhist embroidery in a book assigned for a graduate seminar. The embroidery of Dainichi Nyorai, which is currently in the collection of the Hosomi Museum in Kyoto, dazzled me with its vibrant colored threads and reflective golden mandorla. There's no doubting its visual impact, yet what sustained my interest in the embroidery were the unanswered questions in the book—who made it and why?

I just knew I had to find the answer to these questions and assembled the few sources available on Buddhist embroideries at the time; a 1960s exhibition catalogue and a handful of papers. I wanted to trace the names of their makers, who were often women, back into existence. Initially, the visuals were limited. I worked mostly with black-and-white photographs which required me to stretch my imagination to infer what colors or stitches were being used.

Artist Kazuteru Nakamura (right) has been working to sustain and revive age-old Japanese embroidery and weaving practices.

That all changed in the summer of 2018, when a special exhibition of Buddhist embroideries took place at the Nara National Museum for the first time in 50 years. These embroideries which have miraculously stood the test of time were restored, meticulously catalogued, and photographed. It all felt serendipitous that my 9-month Japan Foundation Fellowship at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies coincided with this historic exhibition.

The first weekend that I arrived in Japan, I visited the museum. I walked through the cool, modern space while all around me, the Buddhist embroideries that I had seen in grainy photographs, vividly came alive. For once, I could make out the fine needlework—the hundreds of stitches contained within a single lotus petal. Up close, its shapes dissolved into countless delicate threads, lines, and patches of color. Just the thought of the hours of work it took to stitch a single flower made me dizzy.

During my fellowship, I discovered that this marvelous Buddhist textile tradition endures even today. I met Kazuteru Nakamura, one of a handful of artists working to sustain and revive age-old Japanese embroidery and weaving practices. He creates traditional Buddhist textiles like the Mandala of the Two Realms and painstakingly reproduces the iconography with exactness so it can be used in temple rituals. The only difference between his works and medieval textiles is that the vibrant colors on his embroideries have not dulled and his use of even thinner miniscule thread.

Carolyn Wargula talks on her research about hair embroideries at Kyoto International Community House organized by the Japan Foundation Kyoto Office.

There are still many discoveries to be made on this topic, which for me, is one of the deepest pleasures of my work. Writing a dissertation is a solitary activity, but the research has always felt collaborative. During my time in Japan, scholars and embroidery enthusiasts alike would mail me newspaper clippings about the discovery of Edo-period embroideries in the countryside of Niigata and Yamagata Prefecture. I would give talks on my research about hair embroideries and college students would come up to me and say, "I finally understand the proverb, 'Hair is the crucial essence of a woman 髪は女性の命' now." Their comments made me aware of the omnipresence of these Buddhist beliefs about female hair; that these hair embroideries live on in such phrases.

Embroidered Buddhist images offer hidden stories of their maker and the world that they inhabited. The inscriptions on the back or a record about its production are sometimes all that we have to trace that man or woman's existence. Their stories are about heartbreak and the loss of a mother, a son, or a daughter. Yet their visuality provides a sense of peace and hope, that their loved one has achieved happiness in the afterlife. The embroidery's color has faded, the ritual practice it was used for seems dated and obsolete, but its subject about the fragility of life still speaks vividly to us even now.

Carolyn Wargula

Carolyn Wargula

Born 1990 in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan, Carolyn Wargula is an American citizen who spent most of her childhood in Japan. She is a PhD Candidate in the History of Art & Architecture Department at the University of Pittsburgh. In 2018, she was the recipient of a Japan Foundation Fellowship and conducted research at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. She is currently finishing her dissertation, "Embodying the Buddha: The Presence of Women in Japanese Buddhist Hair Embroideries, 1200-1700."

Page top▲

Carolyn Wargula

Carolyn Wargula