Poetry? In Postwar Japan: Literary Experiments Beyond the Page

Andrew Campana (PhD candidate in modern and contemporary Japanese literature at Harvard University)

The Japan Foundation organizes the Japanese Studies Fellowships Program and gives preeminent foreign scholars in Japanese studies an opportunity to conduct research in Japan. One of the 2015 fellows, Mr. Andrew Campana, who has carried out his research "Poetry Across Media in 20th Century Japan" at Keio University has contributed an essay titled "Poetry? In Postwar Japan: Literary Experiments Beyond the Page."

When I was in Tokyo a few years ago, I found myself on an Ōedo subway line platform late at night looking at a map to make sure I was going in the right direction. A young and obviously tipsy couple came up to me, and after helping me out, they asked what I was doing in Japan. I said I was a student. They asked what I was studying, and I said Japanese literature. They asked what kind of literature, and I said modern poetry. There was a pause, and then the woman suddenly cried out: "That is SO BORING. You are a BORING PERSON."

Nevertheless, I have continued my research on this topic. Thanks to a Japan Foundation Japanese Studies Fellowship, I have spent the last year in Tokyo gathering materials for my dissertation, "Poetry Across Media in 20th-Century Japan." The viewpoint so concisely expressed by the woman on the subway platform, however, is not an uncommon one. Poetry in general and modern poetry in particular often has a reputation of being irrelevant, overly obscure, or yes, boring, compared to other forms of artistic expression. This even applies to the academic world, in which poetry is sorely understudied, under-written about and under-taught compared to novels, short stories, visual art, and film.

Despite this, I've been driven by a strong sense that poetry still matters, and that it does things that other forms of expression do not. This was the main theme of the talk I gave at the Japan Foundation earlier this year about one aspect of my research in progress, called "Poetry? In Postwar Japan." In the talk, I focused on poetic works created in the 1950s and 1960s in Japan that challenge the idea of what poetry could be--what it looked like, how it sounded, how it was performed, recorded, written down, or even what "poetry" might mean in the first place.

The conventional story of poetry in Japan in the two decades after the end of World War II has pretty much been established at this point. There are several figures and groups that come up again and again in historical accounts, from the bleak and moving works of figures like Ryūichi Tamura, to the women poets like Rin Ishigaki and Taeko Tomioka gaining fame around this time, to the lyrical poets like Shuntarō Tanikawa and Makoto Ōoka who remain wildly popular today.Yet their poems--usually published in poetry journals and then collected into books--were not what interested me the most about the poetry of that era.

What drew me instead was another history of poetry in the 1950s and especially in the 1960s, within and outside of Japan, where countless poets engaged in an expanded conception of poetry, of works both on and off the page that sometimes involved words and sometimes did not. During this time, artistic practice often combined text, film, television, theatre, music, sculpture, dance, photography and so on with wild abandon, a phenomenon that was often later called "intermedia." Some of these works might not be immediately recognizable as poems at first. But putting them at the center of the story of poetry at this time gives us a way to understand how "literature" continually changes alongside new media technologies, artistic trends, and political movements in amazingly flexible and diverse ways, and has the potential to link different worlds together.

An early example of this is the work of Kuniharu Akiyama (1929-1996), poet, music critic, and composer. He was part of the young Tokyo avant-garde art collective Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop) that formed in the early 1950s, alongside sculptors, engineers, poets, and still-famous composers like Tōru Takemitsu and Jōji Yuasa. Japan's first tape recorder was released in 1950, and at Jikken Kōbō's 5th Exhibition in September 1953, Akiyama debuted what were perhaps the world's first-ever "poems for tape recorder," called Sakuhin A [Composition A] and Sakuhin B: Torawareta Onna [Composition B: Imprisoned Woman].

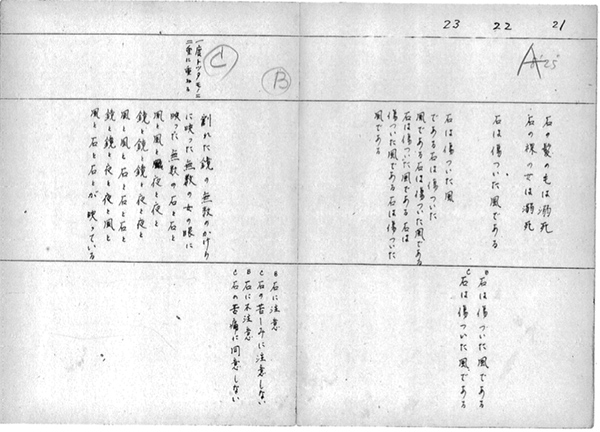

A page from Kuniharu Akiyama's Poem for Tape Recorder-- Sakuhin B: Torawareta Onna, 1953, Private collection

While the recordings of both of these are lost, during this research year, I was lucky enough to have the chance to see the two remaining scripts for Akiyama's second tape recorder poem, which I had only read about before. I was astounded to find that the poem was over 20 pages long, in 36 parts, with many parallel voices, time markings for the recording track, and directions for performance and sound manipulation. It's a lost Surrealist epic--a sonic evocation of an impossible landscape where bodies and nature and structures continually fragment and mutate, with a hypnotic and obsessive use of repetition of certain images (usually mirrors and stones and the night and wind). Here was a poem created the same year as the end of the U.S. Occupation, meant for performance with multiple live and recorded voices coming from off-stage, combining modernist poetic imagery with a structure of looping, stuttering and reversal intimately tied to the cutting-edge media technology of the magnetic tape recorder. It's a poem as manipulated sound, as plural voice, as tech demo, as script, as empty stage, and as lost recording.

Another poet who worked across media was Seiichi Niikuni (1923-1977), originally from Sendai, famous for his radical visual poetic rearrangements of kanji, hiragana, and katakana into "concrete poems." Using a phototypesetter to manipulate characters across the space of a page, Niikuni's concrete poems break apart words into their characters and characters into their component parts, creating meaning not just through their semantic content but in new kinds of graphical relationships. In Kawa/Shū (1966, pictured below as a mural in the Netherlands), for example, the characters for "river" and "sandbank" are not just representations of those words and concepts, but in their repetition and arrangement create the visual image of water flowing past a riverbank.

A "wall poem" version of Seiichi Niikuni's Kawa/Shū in Leiden, the Netherlands Photograph by David Eppstein

Making these types of poems was also important to Niikuni for their potential to be part of a truly global movement. With a simple legend explaining the meaning of each character, his poems can be easily understood by those who don't know Japanese, and so were reprinted in anthologies across the world. Niikuni also created concrete and sound poems in collaboration with a wide range of poets from France, the United Kingdom, and Brazil. His poetry actively wove together the visual and the sonic, literature and art, and even different languages, becoming a tool to tear down the boundaries between disciplines and between nations.

But perhaps more than any other figure, Yoko Ono (1933-) expanded the meaning of "poetry" at this time. She remains, of course, by far the most well-known person from Japan who worked within the global experimental artistic scenes of the 1960s. Yet she, too, often described herself first and foremost as a poet; she started writing poetry at a young age, and it was the main focus of her studies as an undergraduate at Sarah Lawrence College. One of her earliest major works, the 1964 bilingual English/Japanese book of instructional poems called Grapefruit, largely consists of instructions to the reader to perform some task, or to at least imagine themselves performing it. These instructional poems are intended, essentially, to serve as scores for your imagination and/or action, poetically reprogramming your daily life into ongoing performance art.

Another work, Touch Poem #5 from around 1960, takes the form of a book. Its pages are blank except for white paper glued in like lines of text, and several intertwined locks of human hair. This is a poem without words which is read by feel, a combination of sculpture, book, and body, and an early example of Ono's wider strategy of fundamentally rejecting the boundaries between different artistic disciplines, using poetry as one of her main tools of choice.

The Doors, a 2011 installation by Yoko Ono at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art Photograph by Chiaki Hayashi

Those are just three examples of a much wider trend of poets making poems in unusual forms and media in these decades--at the same time, one might have encountered Hideko Fukushima's "autoslide poems" that combined slideshows and recorded recitations, Seiko Kanno's "semiotic poems" of dueling abstract shapes, Mieko Shiomi's "Spatial Poems" that involved people across the world performing tasks based on instructions she mailed to them, Katsue Kitasono's arrangements of photographed objects he called "plastic poems," and Toshio Matsumoto's achingly beautiful "documentary poems," which redefined what documentary filmmaking could be.

We live in a time where digital media is ubiquitous, raising constant questions over the future of humanities and the arts. How will literature change, for example, when the majority of it is read on screens or listened to in audio form on a computer or mobile device? What does it mean to think about literature when it is more and more common to experience it as one form of media among many, sharing the same platform as countless videos, albums, movies, podcasts, and games? These pre-digital poetic works of the 1950s and 1960s in Japan that engage with the new media of their time give us a different approach to these debates. These works bring up the possibility of poetry not as a specific form of expression but as an action or stance towards experience and composition that emerges at the intersections of media, the body, and texts. But, in the end, I hope that through this project I can show just how "unboring" modern Japanese poetry really is.

Back Issues

- 2019.8. 6 Unraveling the Maker…

- 2018.8.30 Japanese Photography…

- 2017.6.19 Speaking of Soseki 1…

- 2017.4.12 Singing the Twilight…

- 2016.11. 1 Poetry? In Postwar J…

- 2016.7.29 The New Generation o…

- 2016.4.14 Pondering "Revitaliz…

- 2016.1.25 The Style of East As…

- 2015.9.30 Anime as (Particular…

- 2015.9. 1 The Return of a Chin…