The Style of East Asian Cultural Exchange: As Seen in the Book Road and Written Communication

Wang Yong (Professor/Director, Institute of East Asian Studies, Zhejiang Gongshang University)

In his research work, Professor Wang Yong suggests the idea of a "Book Road" to describe the primarily intellectual exchange via books between Japan and China. He compares it with the "Silk Road," the famous network of ancient trade routes that extended across Central Asia, connecting the East with the West, and which derives its name from the trade in Chinese silk. He also contrasts the Western style of auditory communication with the Eastern approach that places importance on written communication as the main tool of exchange. Professor Wang, who adopted this creative approach to shed light on the unknown history of cultural and scientific exchange between Japan and China, received the 2015 Japan Foundation Awards. This article presents a summary of Professor Wang's 2015 Japan Foundation Awards Commemorative Lecture titled "Now, He Who is Silent Wins Over He Who Speaks: The Style of East Asian Cultural Exchange," after a verse from the poem "Pipa Song" by the renowned Chinese poet Bai Juyi. In his lecture, Professor Wang presents the progress of his research from his concept of the Book Road to the complex modalities of written communication, and explores the unique style of East Asian cultural exchange exemplified by the relations between Japan and China.

(Excerpt from the 2015 Japan Foundation Awards Commemorative Lecture held at the Japan Foundation, JFIC Hall "Sakura" on October 22, 2015)

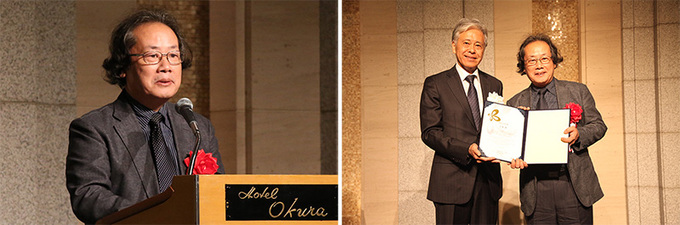

2015 Presentation Ceremony for the Japan Foundation Awards (October 19, 2015)

Professor Wang Yong takes the stage at 2015 the Japan Foundation Awards Commemorative Lecture

Why "the Book Road" and not "the Silk Road"?

Both in science and in humanities, all discoveries begin from simple questions. The idea of the Book Road as well, was born from a question I had.

My interest in this issue was spurred by a verse from a poem by Wang Wei, a poet representative of the Tang dynasty.

"I beg you to drink down another cup of wine

You're going out west of the frontier and you've no friends there"*

In this famous farewell poem, Wang Wei juxtaposes the geographical proximity of the western territories, which are just beyond the Yang Pass, with their spiritual distance as a world that is completely different in terms of culture and customs. * English translation taken from Wang Wei - Poems. 1973. Translated by G. W. Robinson. Penguin Classics

On the other hand, another poem, in which Wang Wei sees off Abe no Nakamaro, a Japanese scholar who participated in the Japanese mission to Tang Dynasty China, reveals the closeness that the poet felt to Japan despite its significant geographical distance from China. In other words, Wang Wei saw Japan as a spiritually close world.

This raised for me the question of what kind of historical circumstances caused such a difference in the poet's perception of the West on one hand and Japan on the other. This query born from the comparison of the two poems led to more questions.

The exchange route that stretches from China through Central Asia to Europe is called the Silk Road. There is no argument about this. After all, this is how silk textiles traveled from China to the West.

In contrast, the route that links China with Japan, two countries not connected by land, is called the Sea Silk Road. Is this, however, the most appropriate description for this route? I could not help but feel rather dubious about using the expression "Silk Road" to describe the exchange between China and Japan.

In the age of the missions to Sui Dynasty China, Prince Shotoku, a regent of the Asuka Period, lamented the lack of books in Japan, which prompted him to dispatch Ono no Imoko, a politician and diplomat, to Sui to purchase books. After the demise of the Sui, missions to Tang Dynasty China were dispatched, and the envoys on these missions brought with them silk, a widely-accepted currency in East Asia, to cover their travel expenses.

This begs the question, would they go to the trouble to trade silk made in Japan for silk made in China? This does not make any sense.

The Western envoys to Tang did indeed purchase silk, but what the envoys from Japan brought back to their country was not silk, but books. This is why I named the exchange route between China and Japan the Book Road.

The millennium-old history of written communication in the relations between Japan and China

As symbolized by the physical artifacts of silk and books, the content of the exchange between China and the West on one hand, and between China and Japan on the other, was very different. This difference existed not only in the items exchanged, but also in the methods, which were defined by quite specific characteristics.

I just referred to Ono no Imoko's mission to Sui Dynasty to purchase books earlier. According to some biographies of Prince Shotoku, during that mission Ono no Imoko climbed Mount Heng, located in Hunan Province, China, where he met with three elderly priests. So how did they communicate without speaking a common language? The answer is, they used written communication.

The same happened during the missions to Tang. Several hundred envoys were dispatched in a single mission, but only few interpreters accompanied them. Most of the envoys used written communication as a means of exchange.

Professor Wang Yong uses slides to explain the modalities of written communication

This does not necessarily mean that these envoys came up with the idea of written communication because they did not understand Chinese. It appears that in some cases the choice to use written communication was consciously made, despite the fact that the envoys could converse with their counterparts.

Written communication was also used when Japanese and Chinese counterparts handled important content or engaged in literary exchanges. For instance, Kosai Ishikawa, a prominent poetry and prose writer and scholar of classical Chinese, used written communication to exchange poems with members of the Chinese legation personnel, and these poems were published as a single volume titled Shizan Issho.

A copied format, which incorporated written communication, was included in the Sino-Japanese Amity Treaty of 1871, the first modern treaty concluded between Japan and China. Article 6 of the treaty stipulates that kanbun (literary "Chinese writing," a method of annotating Classical Chinese so that it can be read in Japanese) shall be used in bilateral negotiations, and when wabun (Japanese writing) is used, it shall be supplemented with kanbun.

In other words, written communication was not something that occurred incidentally. On the contrary, it was a means of communication used intentionally in the millennium-old history of Sino-Japanese relations.

This, however, does not mean that written communication exercised its power only in the relationship between Japan and China. Article 6 of the Sino-Japanese Amity Treaty does indeed stipulate that kanbun shall be used, but kanbun does not mean the "Chinese language." Rather, the term refers to the writing system used broadly in East Asia, or, in other words, to the system of Chinese characters. In fact, there are preserved examples of such written communication between Japanese and Koreans, Japanese and Ryukyuans, Ryukyuans and Taiwanese, and Ryukyuans and Fujianese. It can be claimed that written communication was an essential means of exchange in East Asia.

Regrettably, most records of written communication have been buried away, but the communications between Sun Yat-sen, a Chinese revolutionary activist and first provisional president of the Republic of China, and Toten Miyazaki, a Japanese revolutionary activist who aided and supported Sun Yat-sen, have been preserved. There are also records of the written communication exchanged between a young Zhou Enlai, who later became the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, from the time he was studying in Japan and other students of the art school he attended. I sincerely hope that more such valuable materials will be discovered in the future.

The West absolutizes auditory communication, while the East attaches importance to the written word

In the past, when I spent a year in the United States, I tried hard to explain the concept of written communication. Alas, my U.S. counterparts just could not comprehend it. They understood why people with hearing or speaking disabilities, for instance, would communicate by writing, but marveled as to why non-disabled people would need to use written communication. It appears that in the West, written communication does not fall under the ordinary communication tool category.

Professor Wang Yong explains the difference in perception of language between the East and the West

According to Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, spoken words and written characters are two different sign systems, and the only reason for the existence of written characters is to replicate sounds. In other words, the existence of written characters is meaningless without sounds. In my opinion, however, this concept is inapplicable to the Eastern languages.

Last year, upon assuming the post of Eminent Professor at the Japan Research Center of Fudan University, I delivered a lecture titled "Silent Dialog." I chose this title instead of "Written Communication" with awareness of the Western concepts on this theme.

The term "written communication" could be replaced with "quiet talk," but it is not the same as talking in a small voice. Written communication does not require auditory expression. It enables people to convey their intent without sound, making dialogue possible. In other words, written communication is a silent dialogue. That is the concept behind the title of my lecture.

The West tends to absolutize spoken language as a means of communication and downplayed written characters as mere visual signs. The awareness in the East is different. Sounds are grasped through the auditory perception, so they disappear instantly and do not disseminate spatially. Written characters on the other hand are perceived and understood visually, so they are temporally conveyed through the ages and propagate spatially. That is why we from the East place importance on written characters.

The speech-language barrier caused by not understanding a spoken language greatly impedes communication. Eastern people have overcome this barrier through the means of written communication, thanks in no small part to the power of Chinese characters as ideograms.

I am sure you have experienced a situation in which, even if you cannot read certain Chinese characters, you can intuitively grasp their meaning.

In the West, there are super-humans who speak five or ten languages. Eastern people may be amazed by their formidable linguistic powers cultivated through auditory development. Westerners, on the other hand, marvel at the ability of Eastern people to understand hundreds and thousands of characters that look like complex pictorial figures.

Both Western and Eastern people have their strengths and weaknesses, and it is pointless to focus exclusively on the weaknesses. I call upon all of you to feel confident as Eastern people, because we have some wonderful strengths.

(Text: Sayuri Saito / Photos from the lecture: Kenichi Aikawa)

Wang Yong

Wang Yong

Wang Yong was born in 1956 in Pinghu, Zhejiang Province. He graduated from the Japanese Language Course of the Linguistics Department at Hangzhou University in 1982, and attended the Ohira School from 1983 to 1984. After receiving his master's degree from the Beijing Foreign Studies University (Beijing Center for Japanese Studies) in 1987, he went on to obtain a doctorate from the Graduate University for Advanced Studies (Japan) with his thesis titled "Shotoku Taishi to Chugoku Bunka" [Prince Shotoku and Chinese Culture] in 1996. He is currently Director of the Institute of East Asian Studies at Zheijiang Gongshang University, Eminent Professor of Center for Japanese Studies, Fudan University, and Chair Professor at the Key Research Institute of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Zhejiang Province.

Keywords

- Language

- History

- The Japan Foundation Awards

- Cultural Diversity

- China

- Japan

- United States

- Switzerland

- Institute of East Asian Studies at Zheijiang Gongshang University

- silk road

- written communication

- Wang Wei

- Wang Abe no Nakamaro

- Japanese missions to Sui China

- Prince Shotoku

- Ono no Imoko

- Japanese missions to Tang China

- Kosai Ishikawa

- Sino-Japanese Amity Treaty

- Sun Yat-sen

- Toten Miyazaki

- Zhou Enlai

- Ferdinand de Saussure

- Fudan University

Back Issues

- 2019.8. 6 Unraveling the Maker…

- 2018.8.30 Japanese Photography…

- 2017.6.19 Speaking of Soseki 1…

- 2017.4.12 Singing the Twilight…

- 2016.11. 1 Poetry? In Postwar J…

- 2016.7.29 The New Generation o…

- 2016.4.14 Pondering "Revitaliz…

- 2016.1.25 The Style of East As…

- 2015.9.30 Anime as (Particular…

- 2015.9. 1 The Return of a Chin…