Restoring Rational Dialogue into China-Japan Relations--the Reasons Why I Launched an Internet Petition

Cui Weiping

Writer and former professor of the Beijing Film Academy

In the fall of 2012, violent riots broke out in China in protest against Japan's claim to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, which shocked Japanese society. Since then, relations between Japan and China have failed to recover from the resulting friction.

Despite this underlying animosity, voices were raised in China calling for "rationality in relations between China and Japan." Of note among them was a petition drive, conducted by the writer and former Beijing Film Academy Professor Cui Weiping, to collect signatures over the Internet in support of her appeal: "Let's restore reason in China-Japan relations," which was announced on October 4, 2012.

At the invitation of the Japan Foundation, Cui Weiping visited Japan for the very first time in January 2013 and talked about the background and reasons for launching this petition, and how we should face this issue.

(The following is a transcript-translation of her lecture at the Japan Foundation JFIC Hall "Sakura" on January 29, 2013.)

It's been only three weeks since I arrived in Japan, my very first visit to this country. In what I have experienced in that time, I can say that I have been able to see new aspects of Japan, which I would like to share with all of you here today, and hear what you have to say too. [Since October 2012] I have been inviting like-minded friends to join me in calling for rationality in China-Japan relations, but since arriving here in Japan and actually experiencing life here, I've begun to realize that the words "China-Japan relations" are not adequate to express my thoughts. The words "Japan-China relations" or "China-Japan relations" are terms used by the two governments. Of course, when we talk about the relationship between China and Japan, we are referred to what takes place between two nations, but we shouldn't forget that it also involves relationships between people. So today, I would like to talk about this people-to-people relationship, and how we should approach the future by looking back at the past.

It's been only three weeks since I arrived in Japan, my very first visit to this country. In what I have experienced in that time, I can say that I have been able to see new aspects of Japan, which I would like to share with all of you here today, and hear what you have to say too. [Since October 2012] I have been inviting like-minded friends to join me in calling for rationality in China-Japan relations, but since arriving here in Japan and actually experiencing life here, I've begun to realize that the words "China-Japan relations" are not adequate to express my thoughts. The words "Japan-China relations" or "China-Japan relations" are terms used by the two governments. Of course, when we talk about the relationship between China and Japan, we are referred to what takes place between two nations, but we shouldn't forget that it also involves relationships between people. So today, I would like to talk about this people-to-people relationship, and how we should approach the future by looking back at the past.

On September 15, 2012, riots broke out simultaneously in the streets of many cities throughout China. The experts know that these incidents were masterminded by the authorities. I've heard that before the outbreak, instructions were given to forbid the publication of books and other material connected to Japan. Books written by Japanese, books on relations between China and Japan, books written about Japan by Chinese writers--all plans to publish these types of books were cancelled.

Anti-Japan demonstrations in Shanghai, September 18, 2012 (Photo by Katokichi)

I am of the generation that experienced first-hand the Chinese economic reform of the 1980s, and so when I saw the recent ban on publications, I felt as though China was reverting to the days before the reform. Chinese society seems to be following blindly and reflecting something dark. Rather than being just an issue about China-Japan relations, I feel an even more serious situation is occurring in Chinese society as a whole.

It's a fact that soon after the ban on Japan-related books was put into effect, the street riots began. So I got together with friends to urge people to take their reason back. The call was triggered off by the crisis over China-Japan relations, and I was filled with the desire to make sure that Chinese society did not try to turn the clock back. I didn't want to return to the days of isolation for our country.

China needs to take a role as a member of the international community. Each person needs to possess a wide view of the world, and become aware that he or she is a citizen of the world. Needless to say, I believe that it is these people who support to create a bright future of the society, and this idea was my biggest motivation for launching the petition.

Identifying deeply hidden truth

As I mentioned earlier, it has been said that the violent incidents had the backing of the Chinese government; in other words, it's the view that the government gave permission for the incidents to take place or encouraged them. I have no intention of disputing that view. One thing is certain: various demonstrations have taken place in China, but the anti-Japanese demonstrations were not the type we normally see. What I mean is that the government could have controlled the anti-Japanese violence. We cannot ignore the authority factor in this issue. Authority often goes hand in hand with conflict, but in China, no such thing as an open challenge to authority exists. In other words, ordinary Chinese citizens have no idea how authority is delegated. The ordinary men don't have any way to know who is in favor of the anti-Japanese demonstrations, whether it is one group of people or everyone in the country. This is the dilemma faced by Chinese society today.

If I raise one issue to my Japanese audience, it would be this. You should ask yourselves whether the Chinese have a fixed idea of Japan. Does Chinese society in general have a certain view of Japan? Is this view sometimes given a different interpretation by politicians? Or maybe this is given a broad interpretation and exploited by the politicians? If such a manipulated, imagined hatred of Japan existed, one can also ask if there isn't an inkling of truth hidden behind that view. The truth may have been twisted out of shape, but there may be a need to seriously ask oneself if there is an element of truth hidden there. I believe one must look hard for what is hidden deep out of sight, and give it due reflection.

The loss of opportunity to heal war wounds

Ever since I began the petition in the fall of 2012, a great many thoughts have come to mind. I can't deny the fact that certain bad feelings towards Japan do exist in China. This bitterness has built up over the years and been suppressed. But if someone were to touch it, it would have the potential to explode immediately. Even if the ill feeling was minor, the very fact that it has been suppressed may cause a small flame to explode into a big fire. To be sure, the root of the hatred lies in the lamentable war of the previous century. But the hostilities took place 70 years ago. Why do the Chinese continue to harbor such grievances?

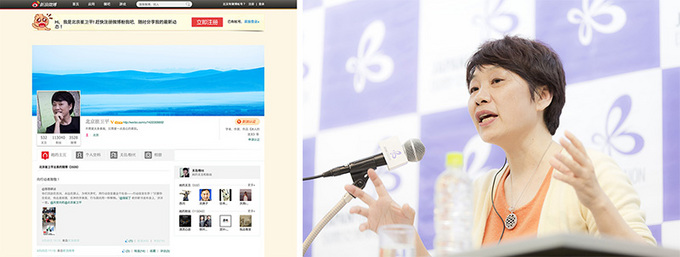

Using Weibo, China's Twitter-like microblog, I posted the following comment that people in Japan have been questioning: "Why so many years after Japan was defeated in the war, do the Chinese continue to hate Japan as though the hostilities took place just recently?

(Left) Weibo (China's microblogging service)

To be sure, the Chinese still remember the tragic incidents of the Second World War. The country has not made an active attempt to solve the issue. In 1945, in the last moments of the Second World War, China fell into a state of civil war, with the Communist Party confronting the Kuomintang, the Nationalist Party. Because of these hostilities within the nation, there were no detailed figures taken of the extent of the damage suffered in the war. Numerous political movements surfaced on the mainland, and people were preoccupied with the immediate dangers they faced. So the people were robbed of the opportunity to deal with the psychological wounds they had suffered in the war. The bitter grief and harsh conditions suffered by the ordinary people were ignored.

The situation was aggravated by the ensuing Cold War. The Cold War had the effect of distancing relations between China and Japan. That meant, immediately after the war, Japan was able to stave off the pressure to pay compensation for the suffering sustained by Chinese citizens. For the ordinary Chinese, the damage they suffered in the war was enormous. The number of lives lost was unknown. But a person only lives once. The experience of the sufferings and losses incurred in the war must be understood, and efforts need to be made to listen to those grievances and to respect those feelings. At that time, though, there were no systems in place to deal with those demands.

Earlier on this trip, I was able to visit Hiroshima where I met a wonderful woman. This woman, the second generation of the atomic bomb victim told me, "My mother was 15 when the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima." When my mother was 15, she experienced the Sino-Japanese War. The Hiroshima woman said, "The war cast its shadow not only on our parents' generation but on our generation, too." On this visit, I realized for the first time that here in Japan, too, there are many cases that exemplify this dark shadow affecting the second generation which had not experienced the war first-hand. The sufferings caused by war are not only those that were inflicted at the time but also the effects on their families and other generations. Perhaps we should pay more attention to the suffering that has been passed down.

What's more, in regard to Japan's invasion of China during the war, if we think of not only the direct damage inflicted on China but also the collateral one, we realize that this was what prevented China from moving into the modern era. In other words, the war deprived China of the opportunity to grow and develop.

40 years have now passed since the normalization of diplomatic relations between China and Japan in 1972. Economic exchanges between the two countries have grown to great heights, but why can't the Chinese people not forget their hatred of Japan?

Since the normalization of diplomatic relations, there have been many official occasions where the two governments have had friendly exchanges. Japan has paid its war debts and given economic aid, but these have been limited to the governmental level.

Now there is a big difference between the two societies. In China, there is no communication between the government and the people. Towards the end of September 2012, Japan's NHK aired a program called "1972--Beijing's Five Days--This is How China Came to Shake Hands with Japan," to celebrate the 40 years since the normalization of diplomatic relations between the two countries. The program told the story of how Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka and his Foreign Minister Masayoshi Ohira went to Beijing to negotiate the deal.

The program looked at some issues faced by China in connection with the normalization of diplomatic relations. It said that the problems left by the war had been ignored for a long time, and so questioned how China was going to present this change of heart to its own people? The program stated that the Chinese government carried out ideological maneuvering to persuade the people to accept the change, saying, "The ties between China and Japan are restored, so let's study all about it now." Once again, the opportunity to assuage the public's memories of the war and their sufferings was lost and people were forced to lock away those feelings.

The Internet is changing public opinion

Chinese society faces another problem. The Chinese media are state institutions and their job is to publicize the government's activities. The Chinese media has not said a word about Japan expressing remorse for its actions against the Chinese people during the war, nor about Japan's economic aid to China. Nor has it mentioned how a great many Japanese have made active gestures to show their friendship with China. The ordinary Chinese have no way of knowing about Japan, including the present situation.

Let's return to the question of why the Chinese still harbor deep-rooted hostility towards Japan. After the resumption of diplomatic ties, the exchanges were mostly on the economic front. Of course the economy is important, but it has its limits. The Chinese government placed its priorities on economic growth, saying, "We must grow," and ignored the wishes of the ordinary people, and neglected their need to enjoy equal rights under the law and social justice.

But things are changing a little in China now, and it has been brought by the emergence of the Internet. Ways of expressing one's opinion have increased enormously and the power of ordinary people has grown stronger. Individuals are now conscious of the fact that their power is growing. By seizing these opportunities to have their say, people are eager to give vent to the resentments that have built up over the years, including their bad feelings towards Japan, and they are seeking further opportunities on the Internet to articulate that social bitterness.

Some people believe that the anti-Japanese demonstrations in September 2012 are due to the rise of Chinese nationalism over the Internet. For Japan, this is a new type of pressure, pressure coming directly from the Chinese public.

I, personally, do not support racism or nationalism, or any exclusionist movements, but as we witness the surfacing of numerous different views, we realize that the feelings of the ordinary Chinese people that were suppressed for so long have now erupted.

[In the past], especially regarding China-Japan relations, the government took the lead in how people thought. So the sort of situation we are witnessing now would not have taken place. The attacks and criticism leveled against Japan that we are seeing on the Internet would not have happened in the days of Deng Xiaoping or Hu Yaobang. So, Japan is now facing a new situation.

Of course, people shouldn't resort to violent riots or inflammatory speech. But in the background, there are "feelings" that need to be given voice. We must face these feelings squarely and think of ways to deal with the situation.

So, how should we solve these problems? Japanese experts stress the need to promote exchanges at the grassroots level. There are similar views in China too. Both countries need to encourage exchanges on the civic level, and people should get to know each other by meeting face to face. But we still don't know how this can be realized--what routes can be taken and who should be chosen to take part? In China, it is illegal to set up independent non-governmental organizations, so it would be very difficult for Japanese NGOs to find counterparts in China.

That being said, you couldn't have 1.3 billion Chinese all coming to visit Japan [to see the country for themselves]. So, what should we do? Well, although independent non-governmental organizations don't exist in China, there is social public opinion. Instead of using the state-controlled media, the public can have their say directly over the Internet. My suggestion is that if the Japanese want to have exchanges with ordinary Chinese citizens, a very effective way of achieving this would be to encourage social public opinion in China to grow stronger.

Common values as human beings

What should be the most important factor in people-to-people dialogue? At the grassroots level, the most basic perceptions and expectations of one individual for another would be a regard for principles--a person's rights and moral standards.

What should be the most important factor in people-to-people dialogue? At the grassroots level, the most basic perceptions and expectations of one individual for another would be a regard for principles--a person's rights and moral standards.

Ever since I arrived in Japan, I've posted comments on what I've seen and heard here on the Weibo site so it can be read back in China. On one occasion, I talked about a Japanese lawyer who is supporting a Chinese citizen in a court case. Another time, I described how a Waseda University student travelled to Yunnan Province in China and offered to look after a Chinese person suffering from measles while he was there. The reaction to these stories was amazing. Many Chinese said that they were impressed with how Japanese people could have such a caring attitude towards their fellow human beings.

When I told my father I was coming to Japan, he said, "If I were you, I wouldn't go." He has strong feelings against Japan. But when I told him about the Japanese who had shown such concern for individual Chinese, and about how a Japanese friend had apologized about the war, my father commented, "It's like in the days of Deng Xiaoping." During the Deng Xiaoping era, the friendship with Japan was promoted in China. So when people hear how the Japanese can show great sympathy for the Chinese, even someone as old as my 94-year-old father can change their view.

In my opinion, the ordinary Chinese are among the world's most kind and humble people. They're not after monetary compensation. They want to have their moral rights respected and redressed.

Regarding the relationship with the Japanese, whether it be concerns about the past, present or future, the Chinese want to be treated as equals and want to be respected. Be they Chinese or Japanese, both should reflect on past actions, and look hard at the present and future, and take moral responsibility for their actions.

In discussing the war with an eye to both the present and the future, it is necessary to gain the understanding of ordinary Chinese and Japanese people. I believe it is essential for the two sides to make amends and look towards the future together.

China, whose modernization was hindered by the war, is now facing a crucial turning point. Society needs to undergo a model change and the country is trying to convert itself into a democracy. So, at a time like this, it is especially important that China is on good terms with its neighbors. If the two countries face a new crisis, China's democratization will be delayed seriously for sure. That is why I would like the Japanese people to understand this situation and look at Chinese society with a generous heart. Although it is slow, China is surely making progress. I would like the Japanese to welcome this move. I think it is Japan's moral duty and its expected role. I would like to ask you to cooperate in building a strong, caring relationship between the two countries.

(Editor: Ayako Tomokawa, Photos: Kenichi Aikawa)

Junko Oikawa's reflections on the lecture

On October 4, 2012, Cui Weiping launched her petition over the Internet urging people to join her in restoring rationality in China-Japan relations. In the fall of 2012, the relationship between Japan and China deteriorated due to conflicting claims to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and violent demonstrations broke out in China. This state of affairs greatly saddened Ms. Cui and prompted her to begin this appeal. In the first stage, 75 people signed the appeal, including researchers, journalists, artists, and human rights activists. The appeal spread over the Internet and the list had grown to 793 signatures by the beginning of November.

On October 4, 2012, Cui Weiping launched her petition over the Internet urging people to join her in restoring rationality in China-Japan relations. In the fall of 2012, the relationship between Japan and China deteriorated due to conflicting claims to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and violent demonstrations broke out in China. This state of affairs greatly saddened Ms. Cui and prompted her to begin this appeal. In the first stage, 75 people signed the appeal, including researchers, journalists, artists, and human rights activists. The appeal spread over the Internet and the list had grown to 793 signatures by the beginning of November.

This appeal got underway, actually, after a group of Japanese editors, journalists, writers, lawyers and civic movement leaders made an appeal on September 28, 2012, to look for a solution to the vicious circle of territorial disputes. The Japanese appeal was not limited to the issue with China but also the ongoing dispute with South Korea over the Takeshima/Dokdo Islands, and other territorial issues in East Asia, as well as the question of Japan's interpretation of historical events. It sought a solution to these issues through dialogue and urged the Japanese government to take a responsible stance in these matters.

The Japanese grassroots appeal was also translated into Chinese and posted on an influential website in China. When Ms. Cui and her friends read this, they were moved to rally support for the Japanese appeal. So this was the background to Ms. Cui's petition and she tells the story at the beginning of her petition.

At a time like this, when relations between Japan and China are extremely tense, it is truly meaningful and important that dialogue is taking place between ordinary people over the Internet and that both sides are urging the need to be rational.

In Ms. Cui's appeal, in relation to the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands, she states that China should put the issue on hold once again. And as far as attitudes to the Japanese are concerned, she says the Chinese should be fully aware of what took place in the war, but that they shouldn't resort to violence or try to stir up hatred. At the same time, she says, the Chinese should learn how the Japanese have lived since the war, how it has contributed to China's peaceful development, and in this way acquire an accurate picture of the true Japan.

The petition goes on to warn against being influenced by a narrow sense of nationalism and reminds people that because they have the right as citizens to express their opinions on state sovereignty, the government is duty bound to listen to their point of view. And it says that violent anti-Japan demonstrations should not be tolerated and that it was regretful that the situation has grown to the stage of obstructing cultural exchanges. It also urges that both countries include an honest description of modern history in their school textbooks, and open up further channels so that exchanges at the grassroots level can grow. I think that the title of the appeal, "Let's restore reason," describes the essence of the petition in a nutshell.

The lecture transcript reminds me of the excitement that filled the hall that day. Thanks to the cooperation of a great many people, everyone was able to share in the fruits of that day's meeting. The questions and comments from the floor showed Japanese people's realization that something would have to be done quickly to restore friendly dialogue between our two countries, and their concern about how they should approach this issue. Some members of the audience were surprised by the fact that the younger generation of Chinese, who had no direct experience of the war, should have so much hatred for Japan. And many people showed an interest in learning about the changes that have taken place in Chinese society.

Although Ms. Cui made repeated references to the Chinese people's feelings of hatred towards Japan, she also stressed the importance of maintaining moral justice in the relationship between Japan and China, since the ties between human beings were based on justice and morality. By moral justice, Ms. Cui meant that people should treat each other as equals, acknowledge one another's rights and show respect for one another. How did this message appeal to the audience?

As a member of the audience, I was impressed by the way Ms. Cui encouraged people to have their say and responded enthusiastically to all the questions put to her. This lecture conveyed Ms. Cui's idea that even if our stance or opinion differs, we should respect each other's opinions and discuss about these conflicts rationally. And I think the lecture surely encouraged the audience to share her belief that these attitudes would eventually lead to the improvement of Japan-China ties. Numerous issues and problems face our two countries but I would suggest, as neighbors living in the same moment of history, we should join in the creation of shared values.

Cui Weiping

Cui Weiping

Former professor of the Beijing Film Academy. Born in Jiangsu Province. She completed her graduate studies at Nanjing University and is well known for her comments on the independent cinema. As well as being a jury of the China Independent Film Festival, she is a social critic of such areas as human rights and an expert in East European politics.

She has published numerous books and essays, such as Daishang de liming (Qingdao publishing Group), Kanbujian de shengyin (Invisible Voices, Zhejiang People's Publishing House), and essay Wo jianguo meili de jingxiang (Baihuazhou literature and art publishing house). Cui is one of the members who drafted Charter 08 which called for reforms to the Chinese political and social system, including an end to the Chinese Communist Party's single-party dominance, a call for a separation of powers, the promotion of democracy and the protection of human rights. On December 12, 2008, she announced an appeal for the release of Liu Xiaobo (who was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010). In the fall of 2012, in response to the outbreak of violent anti-Japan demonstrations, Cui issued a 10-point proposal over the Internet calling for a return to rational dialogue in the territorial issue and began to collect signatures.

Junko Oikawa

Junko Oikawa

After earning her doctorate degree from Graduate School in General Social and Cultural Studies, Nihon University, she served as an expert researcher at the Japanese Embassy in Beijing. She currently serves as a visiting academic researcher of Hosei University, a visiting researcher of the Institute for Northeast Asian Studies at J. F. Oberlin University, and an adjunct instructor of Nihon University. Her areas of expertise are modern Chinese intellectuals, speech space, and political culture studies.

Her works include Gendai chugoku no genron kukan to seiji bunka--"Li Ei nettowaku" no keisei to henyo (Free speech forum and political culture in present-day China--the rise and restyling of the "Li Rui network", Ochanomizu Shobo); co-translations: Tenanmon Jiken kara "08 kensho" e (From the Tiananmen massacre to "Charter 08," Fujiwara Shoten); Chugoku netto saizensen--"joho tosei" to "minshu-ka" (Forefront of China's Internet--"Information control" and "democracy," Soso Sha); Ryu Gyoha bunshu--Saigo no shinpan wo ikinobite (Liu Xiaobo's collected essays--surviving the last judgment, Iwanami Shoten); Ryu Gyoha to chugoku minshu-shugi no yuku-e (Liu Xiaobo and the future of democracy in China, Kaden Sha); "Watakushi ni wa teki wa inai" no shiso (The "I have no enemies" belief, Fujiwara Shoten); and others.

Back Issues

- 2019.8. 6 Unraveling the Maker…

- 2018.8.30 Japanese Photography…

- 2017.6.19 Speaking of Soseki 1…

- 2017.4.12 Singing the Twilight…

- 2016.11. 1 Poetry? In Postwar J…

- 2016.7.29 The New Generation o…

- 2016.4.14 Pondering "Revitaliz…

- 2016.1.25 The Style of East As…

- 2015.9.30 Anime as (Particular…

- 2015.9. 1 The Return of a Chin…