Fukushima in the Heart of Germany: Reflections on German News Coverage During the Crisis

Alexander Görke

Free University of Berlin

Crises, conflicts, and disasters do not occur simply in a natural sense. On the contrary, particularly under the conditions of comprehensive mediazation of society, we should understand such events as the result of an all-embracing constructional process. The term "crisis" functions as a collective category for a number of different events, and does not exist independently of the perception of the observer. However, a crisis also shows certain characteristics, for example, an unexpected threat that questions not only certain values but also the system and expectations of continuity, and it does so in diffuse ways and under the pressure of time. Further, the underlying events are marked by particularly high actuality, or in other words, the general acknowledgment that a crisis has high informational value and great social relevance. Within this social constructional process, journalism (as so-called mass media) bears a key role because the public, lacking its own direct view, usually learns from the media all they know about a crisis, or all they think they know, for instance, what they know or think about the crisis in Fukushima. This automatically raises the questions: In what ways are the news media operating and how capable are they? On the one hand, some people hope that factual, balanced, and unsensational journalistic coverage of a crisis can help to coordinate supporting measures, defend against subsequent damage, and prevent future crises. On the other hand, if journalistic coverage is too hesitant, trivializing, and conciliatory, it can contradict the interests of the public that wants an adequate picture of the situation and wants to be forewarned about imminent danger. This again conflicts with the worry that overly critical news coverage of a crisis by the media can alienate the public, stoking panic and pushing the public into depression and paralysis. But these kinds of far reaching and rather long-term effects can hardly be verified in a scientific way. However, what we can show is that, for one, the public changes and adjusts its way of using the media in times of crises. And secondly, we can show that changes in the way the public perceives the media interact with changes in journalistic production.

Changing ways of media use and public expectations during a crisis

In times of crisis people watch more television, listen longer to the radio, and read more newspapers and internet reports than they normally would. Not only does the time they use the news media increase, but media use also becomes more intensive in terms of quality. This means the contents offered by the media are generally used more attentively, and even when people listen to the radio or watch television while doing something else, they do so in order to check whether important events are unfolding. The public seeks information on any important event the instant it occurs. Contrary to our everyday use of media, the priority of use shifts away from entertainment and toward information content. This applies mainly to information seeking as well as to priming and framing. We were able to see this during the Fukushima crisis when Japanese media consumers increasingly accessed the online reports of overseas media (e.g. Bild.de). Since during a crisis the media naturally reports on the calamity and its causes and effects, this information will influence the decisions and opinions of the public more than it would during times of normal news coverage (priming). Moreover, information which has nothing to do with the crisis will also be seen in the light of the crisis (framing). Both priming and framing boost the chance that individual media users will feel personal concern or involvement. And this in turn changes the way in which media information is processed. I will return to both aspects at a later point.

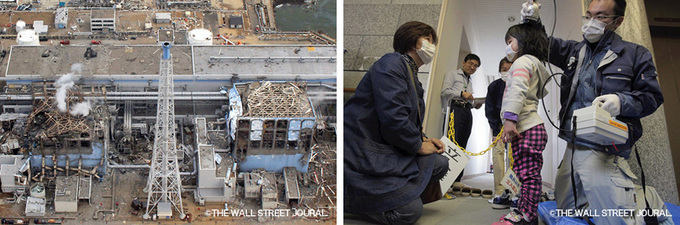

Changing ways of media use result not only in more intensive use and different perceptions of present and past events, but also affect the emotional culture of information processing. Not only rational thinking, but also the feelings of the media audience are subject to a crisis-specific kind of modalisation. In times of crisis, the way in which the media influences the emotional state of the media audience changes in two respects. First, there will be more information stimulating the public. Pictures from crisis regions play a particularly important role in this respect. Second, the influence of negative evaluation will become more likely. Excitement stirred up will more often be connected to threats, possible damage, violence and even death, and mainly negative emotions such as grief, fear or anger will develop in the public as a result. But emotions like compassion, sympathy, and admiration will also develop. (It is not by chance that the illustrated magazine stern chose "Proud, disciplined, unselfish, able to suffer. An unbelievable people. How culture and catastrophes have shaped the mentality of the Japanese" for the headline of their cover picture.)

Journalistic communication of crises

Journalists pay great attention to crises, mainly because an abundance of news factors can be attributed to them. Whether or not an event is considered a relevant crisis (or is mostly left unattended) depends on, amongst others, aspects such as changing quantities (number of casualties, scale of damage), the grade of affectedness (of the country and/or of selected citizens of that country), the possibility to personalize the event (persons who make decisions, persons affected, persons responsible), the involvement of elite nations (Western industrialized nations versus developing countries), the extend of offence against existing law (environmental, safety, and building construction regulations) or against ethical values (the right to know), the extend to which the event can be visualized, the surprise aspect, and the aspects of religious, political, cultural, and economical distance and/or adjacency. These routines of selecting and constructing news are helpful particularly at times when journalists cannot directly rely on sure knowledge and multiply affirmed sources of information, as in the event of the Fukushima crisis where they had to find their orientation in the general situation of not-knowing, in the same way as the players in science, politics, economy, and the public had to do.

Considering this background, we can show that the German media had a number of reasons to report about Fukushima. Both countries share a common history (World War II), the rise to become leading industrialized nations, a common myth about prosperity, and the rejection of military use of nuclear energy. Seen against the background of important values in the respective countries, we could almost say that Germany and Japan are functioning as role models for each other (although staggered in place and in time). Differences between the two countries apply to the evaluation of civil use of nuclear energy. For example, in Germany--unlike in Japan--the anti-nuclear movement has a long tradition reaching back to the 1970s, even refuting the peaceful use of nuclear energy. There are also differences in respect to the routines of news coverage: while obviously Japanese media coverage of the Fukushima crisis was mainly characterized by a strict (and some people say, exaggerated) informational journalistic style, in Germany, relatively critical and investigative journalistic coverage patterns, which have been used traditionally, were applied in this case, too, in addition to the informational style. This resulted in different judgments about which information should be released to the public and at what time. For instance, while the German public had already been informed in March, with the media quoting the opinions of experts, that a nuclear meltdown had most probably occurred in Japan, this news reached the Japanese public through the media not before the beginning of May.

The fact that German news coverage raised questions relatively quickly as to the culpability of those responsible for the Fukushima catastrophe can also be viewed as part of the investigative tradition of German journalism. In this sense, earlier and more critically than the Japanese media, the German media in their news coverage tended to describe the Fukushima reactor catastrophe as a crisis explainable through the social environment. At this point, a singular one-time crisis can change into a crisis of multiple systems. In this sense, a multiple system crisis such as the Fukushima reactor catastrophe threatens not only the future existence of a certain town or region, but can also be understood as an economic crisis (stagnant economic growth, negligible investment in nuclear power plant safety measures). It also questions the national system of political crisis management (failures by government and by the national atomic energy authority). Furthermore, it focuses on the level of supply that citizens feel entitled to (a stable supply of energy from nuclear power plants while facing the danger presented by the geographical location of these power plants in a region prone to frequent earthquakes). And finally it throws a sharp (critical) light on the consensus strategies among nuclear power plant operating companies, politicians, and journalists who kept these problems too long from the public.

Phases and frame conditions of crisis news coverage

Journalism plays a synchronizing role by providing society with the means of self-observation, even if only momentarily. While journalism observes certain sections of society from an outside position (as for instance, economy, science, politics, religion), it also opens up and forces new, surprising, unplanned and therefore often creative insights for members and their actions in these sections of society. In this sense, journalism functions as a metronome of world society. However, hardly any observer outside of journalism will fail to evaluate journalists as problematic, or at least ambivalent, in their dealing with crises. It is understandable that politicians and entrepreneurs grow angry when economic or political crises are debated in public according to the selection criteria of journalists in a process where, because of the system itself, they are counted on for a measure of restraint while serving as the personification of responsibility. Some (affected) politicians, bureaucrats or entrepreneurs might find it inappropriate that a catastrophe like Fukushima is being transformed into a social multi-crisis system in a journalistic way. Seen as a whole, affected sections of society, as well as societal decision-makers and their self-interests, are being put to the test. They have to adequately react to new challenges, or at least they have to justify why, from their point of view, an action is unnecessary at that point. Then the public can draw their conclusions from both. In other words, the way in which society deals with a crisis shows how society learns or fails to learn. But it is also true that learning is sometimes a painful process.

Looking at different events (Hurricane Katrina, the tsunami catastrophe in Southeast Asia, and the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster) we can further note that journalistic crisis communication often follows a certain pattern. Generally we can observe the five phases of monopolization, domination, normalization, marginalization, and re-actualization. The phase of monopolization is characterized by the live characters of news coverage, many external experts, and around-the-clock coverage. In the phase of domination, other topics find their way onto the public agenda and the broadcasting time allocated to crisis reporting is significantly reduced. Also during this phase, however, questions on the background of the crisis are increasingly put forward; not only does the public want to know about the situation, they also want to know what lies behind the facts. The phases of normalization and marginalization mark in a way the (journalistic) end of the state of emergency and the return to a well-rehearsed news routine. Depending on new aspects observable as a crisis or simply because of distance (for instance, the anniversary of a catastrophe), the immediate situation may be reviewed and reprocessed. The overall picture shows that patterns of media use typical to a crisis on the recipient side and production routines typical to a crisis on the journalistic side interact with each other.

But journalistic news coverage of a crisis is not only shaped by professional news routines, specific production routines during a crisis, and the expectations and usage patterns of the recipients connected with this. There is news coverage before any crisis as well as journalistic frame conditions which differ from country to country. These contextual conditions may be technological, economic, cultural, political or even situative. Thus, the Fukushima coverage in Germany becomes understandable not only on the basis of facts internal to journalism, but also on facts external to journalism. Therefore, the way in which the German media reported on the nuclear power plant disaster in Fukushima must not be viewed independently from the fact that over the past 40 years of German policies, first its internal policies and later on also its environmental policies, were more or less continuously influenced by disputes--sometimes clear, sometimes not so clear--surrounding the peaceful use of nuclear energy. This provides the context in which the actual German news coverage of the Fukushima crisis is being handled. Last year's autumn decision by the German government to delay the decommissioning of German nuclear power plants provides another (political) frame. This decision to delay decommissioning was based, among other things, on the argument that nuclear power plants had a particularly high level of safety in Western industrialized countries. Against this background, from a journalistic point of view, news coverage about the Fukushima catastrophe is connected with the "political" catastrophe of a government forced to revise a decision recently pushed through parliament, against acrimonious resistance of the opposition and broad parts of the general population. And finally, the upcoming elections in some German state parliaments are another factor that decisively influenced German reporting on Fukushima. In other words, when for instance the magazine Spiegel led one edition with the title "The end of the nuclear age", the reason for this was not primarily the view of the situation in Japan or even issues on the future of nuclear power. Rather, the view was first and foremost related to the situation in Germany.

Summing up we can say, although there are similarities in the way the crisis was covered by the news media in Japan and Germany (for instance, informational journalistic news coverage and phases of coverage), there are also differences in the way the Japanese and German media reported on the Fukushima disaster. On one side these differences are due to reasons internal to journalism, with different expectations of the public also playing a certain role. On the other side, they are due to frame conditions external to journalism, under which journalists work both inside and apart from critical situations in their countries.

Symposium "The Disaster and the Role of Conventional and New Media--A Comparative Look at How Japan and Germany Reported the Earthquake"

Professor of Media and Communication Studies focusing on knowledge communication and science journalism at Free University of Berlin. Previous to that, doctoral research on "Risk journalism and risk society" at the University of Münster, and teaching and research work at Ilmenau University of Technology, Friedrich Schiller University of Jena, University of Siegen, and University of Münster.

Contact: Alexander.Goerke@fu-berlin.de

Related Events

Back Issues

- 2019.8. 6 Unraveling the Maker…

- 2018.8.30 Japanese Photography…

- 2017.6.19 Speaking of Soseki 1…

- 2017.4.12 Singing the Twilight…

- 2016.11. 1 Poetry? In Postwar J…

- 2016.7.29 The New Generation o…

- 2016.4.14 Pondering "Revitaliz…

- 2016.1.25 The Style of East As…

- 2015.9.30 Anime as (Particular…

- 2015.9. 1 The Return of a Chin…