Yasuhiro Suzuki Connects the Neighborhood with the Globe

The London Design Biennale 2016 was an international design exhibition held in September 2016 that saw the participation of 37 countries. Yasuhiro Suzuki, an artist who creates artworks based on concepts taken from discoveries and memories in daily life, was chosen to represent Japan at the exhibition. Suzuki, who had recently reconfirmed his artistic position by holding a large-scale solo exhibition at an art museum, responded to the theme of the Biennale, "Utopia by Design," with the words "neighborhood globe."

What exactly does Suzuki mean by "neighborhood" and "globe"? Together with Noriko Kawakami, who served as the curatorial advisor for Japan's participation, Suzuki looks back on the Biennale.

Artist Yasuhiro Suzuki (left) with curatorial advisor for the London Design Biennale 2016 Noriko Kawakami (right)

Participation in the Biennale

- The advisory committee for the London Design Biennale, held for the first time in 2016, consisted of Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Motomi Kawakami, Kozo Fujimoto, and you, Noriko Kawakami, and the committee selected Yasuhiro Suzuki as the artist to participate. Can you give us some background on that?

Noriko Kawakami (NK): Almost everything about the Biennale, including the taste of the exhibition, was completely unknown to us, not least because it was being held for the first time. What we did know is that it was the realization of something long planned by the primary members of the group that had launched the London Design Festival. We also knew about the overall theme of "Utopia by Design."

Given that this theme was raised in the Europe of today, we guessed that a theme related to proposals regarding the issues faced today in Europe, such as war and the refugee problem, would be presented. When we thought about what Japan could show to that kind of theme, all of the committee members agreed that we wanted to select someone who could provide a clear viewpoint. We wanted to show the importance of the viewpoint itself.

- What do you mean by viewpoint?

NK: Rather than seeing a utopia as something imaginary, it was the viewpoint that could create an opportunity for audience to think of utopia as something that is within reach. It also meant a viewpoint that can serve, through flexible thinking, as a bridge between things that do not normally connect with one another.

- What was your response to this, Suzuki-san?

Yasuhiro Suzuki (YS): I was very perplexed (laughs). Of course I was honored, but I am also always aware that I know less about myself than anyone does. I believe that the acts of creating a work of art and of arranging an exhibit are fundamentally different. Consequently, I was able to get started thanks to the cooperation of Noriko Kawakami as curatorial advisor.

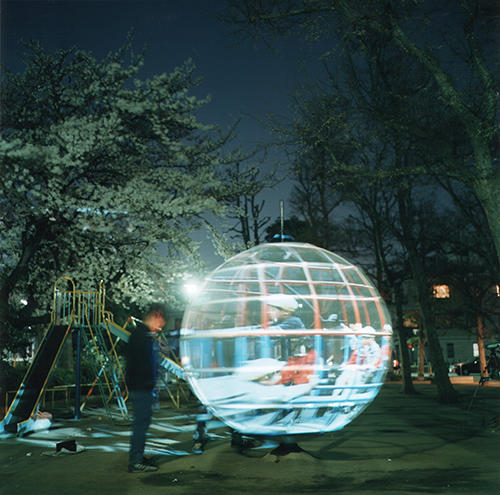

Let me go back for a moment before talking about my exhibit in London. Digital Stadium (a television program featuring publicly-solicited artwork on NHK BS 2, known for launching the careers of many media artists in particular) provided me with an important opportunity for beginning my artistic career with the presentation of my work Perspective of the Globe Jungle in 2001. Looking back, it felt at the time that my work was making its own way in the world, and I was doing my best to keep up with it. I don't believe I was truly an artist yet at that point.

I was taught at an art university, so I was instilled to some degree with knowledge and preconceptions about what art and design are. Consequently, my work Perspective of the Globe Jungle followed the ready-made concept proposed by Marcel Duchamp, who is perhaps the originator of media art, by using playground equipment, a preexisting object, specifically the type of playground equipment that was mass-produced in Japan after WWII, to pursue a new mode of expression by repurposing it as a screen and as a way to present video in a public space.

Perspective of the Globe Jungle. Photo: Rinko Kawauchi.

- For Perspective of the Globe Jungle, you let a spherical jungle gym nobody was playing on spin and then projected video of children playing onto the surface, correct?

YS: I believe I was able to play video that was generated there on the spot, instead of video that preexisted as a piece of information, by having it emerge as an afterimage rather than projecting it onto a fixed screen. Because there was a mood at the time that valued converting all types of experiences into information using computers, we tended to actively make use of media technology. I myself was using new technology, but I also had certain unease towards information technology that I was unable to shake off. I believe that was apparent in Perspective of the Globe Jungle.

However, when I actually put it on display in a park at night, the viewers reacted to aspects that were completely different from the original concept. Young children and elderly men and women would instead talk about their memories involving playground equipment, apparently with great happiness. At that time, I had no idea what evoked this reaction in everyone. And to be honest, I couldn't even express this in words until a few years ago (laughs bitterly).

- Did something else happen that made you enable to do that?

YS: Yes. It was my solo exhibition in 2014 at the Art Tower Mito Contemporary Art Gallery entitled The Neighborhood Globe.

What is the Neighborhood Globe?

- The title of your solo exhibition at the Biennale was A Journey Around the Neighborhood Globe, so I am guessing that there is a direct connection between the two.

YS: "The neighborhood globe" is a phrase I wrote in my notebook in 2001. I think that the words "neighborhood" and "globe" are generally unrelated in daily usage, but for the past ten years, I have noticed that by creating works related to the concept that "neighborhood" represents things that are familiar, my feelings and reality were being broadened, such that they were on a global scale and far removed from daily life.

By nature, I am the type of person who has no interest in going overseas. I discover many things just by walking around my neighborhood on a daily basis, and I myself change by these discoveries accordingly. So speaking personally, I am quite busy every day and don't have the time to think about going overseas. I had been working with a sense that there was no need to expand my horizons to that extent.

But unexpectedly, the works created by someone who likes to stay in his neighborhood began to be invited overseas, and as the artist, I had no choice but to go set up the exhibits. Each time, I would return with what was for me a new sense of strangeness towards my surroundings.

In the current era, things, information, and even people gained the ability to come and go freely. The concept of "the globe," as knowledge and information, was individually suspended, and I felt I had to somehow integrate that "globe" with the "globe" beneath my feet that I felt I understood through experience. The phrase that came to mind as a result was "the neighborhood globe."

Certainly, the globe is big. But if we try to understand this piece of information correctly and objectively, everyone is looking at this limited globe from the same viewpoint. At the same time, if we stay in our own neighborhood and look at the numerous changes around us, we will encounter a constant stream of unexpected things. The extent and reality of this place called "the globe" can change in many ways if you change your approach or viewpoint. For that reason, the concepts of "the globe" held by each individual in the neighborhood are incomparably diverse.

While preparing for my solo exhibition in Mito, I was able to rediscover this neighborhood globe which I had thought up as a way of defining my own position in 2001. Thinking back on that now, I can say that the neighborhood globe is in fact my own personal utopia. And I learned through the exhibition that the same thing existed latently in each person, not just me.

- That realization is reflected in the title of your exhibit at the Biennale. A Journey Around the Neighborhood Globe was comprised of approximately 70 works consisting of both past works that were touched up for the exhibit, and new works. What were the responses like in London?

The Japanese exhibit at Somerset House

YS: Many attendees looked at my work very carefully, spending much more time than I had expected. The other thing that surprised me was that I received almost the same reaction from the people in London this time as the reaction I had for my first overseas exhibit of Perspective of the Globe Jungle in 2002, though the works this time did not yet exist then. The feeling I had 15 years ago came vividly back to me.

NK: Even from my position on the side, the reaction was quite surprising. Considering it was an international exhibition with participants from 37 countries, our prediction had been that attendees would quickly pass through all of the various galleries spending a limited amount of time in each. Otherwise they wouldn't be able to see everything. But with his exhibit, everyone stayed at least 30 minutes, and there was even a line of people out in the corridor waiting to get in. For instance, there were parents and their children who had a discussion in front of each work. And, once they realized that the artist himself was there, they would run toward him to say, "You're Suzuki, aren't you? I really enjoyed your exhibit," before leaving. There was hardly any time to take a break (laughs).

YS: It was clear that they wanted to say something to me before they left. That was similar to when I exhibited Perspective of the Globe Jungle. For whatever reason, everyone looked so happy, even shaking my hand, and they would say "thank you" and leave.

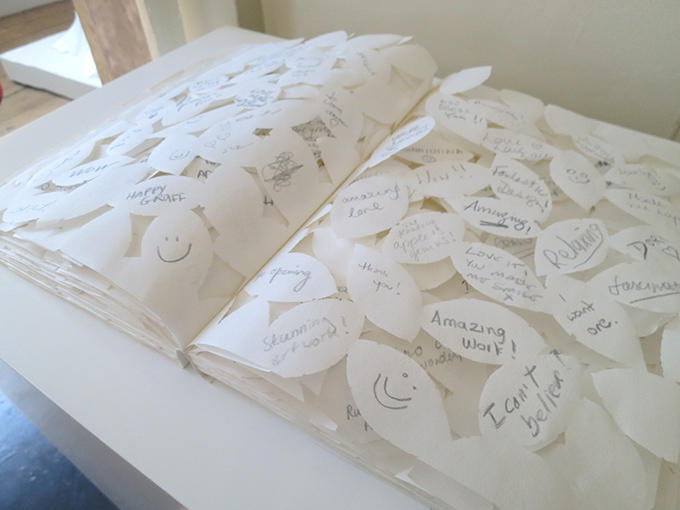

The attendees left many comments for the question asking about utopia in the guest book at the exhibition space.

NK: The atmosphere at our exhibition space was different from the others. Some of the attendees described it as friendly. As we explained at the beginning, the overall theme of the Biennale was "Utopia by Design," and just as we expected, there were many exhibits by designers and architects that proposed specific solutions or methods for sharing information about the severe conditions of society. I myself became quite optimistic, impressed by how well the issues had been presented, thinking that this was the true power of design. But there was also the complexity of interweaving the deep problems of society.

YS: Perhaps our exhibit made everyone forget that (laughs).

Where is utopia?

- This question is for Kawakami-san. What was your understanding of the theme of "Utopia by Design"?

NK: Design is the act of thinking hard to create the world of tomorrow, so I believe the theme points to the very nature of it. Therefore, I felt it was not something you can easily find an answer. While we held a workshop as part of our preparations to study Thomas More's Utopia, which was the reason why the overall theme of the Biennale was chosen, we decided early on not to reflect that work directly.

YS: Before participating in the Biennale, the extent of my understanding of utopia was that it was simply the ideal world, but I learned that in fact the concept existed inextricably with some reality that was difficult to accept, and that it was therefore always something ambiguous. Then I started understanding utopia through this relationship.

NK: You wrote in your exhibit statement that "(Utopia is) another place that is not this place."

YS: The globe we learn about in science class and the globe we observe using GPS, are both pieces of information, which we don't actually have contact with. But in fact it is difficult to really gain a direct visceral sense of either globe, both the information globe and the one beneath your feet. I believe it is instead something that you begin to grasp through daily trial and error in everyday life through using various types of media. What I personally needed when I became a member of society was some kind of response obtained from trying out different methods that were appropriate for me. This was also essential for me as I considered trying to become an artist after graduating from university in 2001, rather than getting a job. It may sound too dramatic, but in fact it was because I felt that I would lose sight of my position in the world if I didn't rethink things radically.

So, to summarize my career so far, at this point, it seems that the title I gave the work in the beginning, Perspective of the Globe Jungle, was a name that sowed the seeds for further expansion in future, even though it was not very specific at that point. For the Japanese title of the work, my choice to use the name of a specific type of perspective rather than the general term allowed me to put off discovery and decision to move towards something latent and invisible.

And then there's the jungle gym. A tool appears to be something that was made with a purpose, but in fact a jungle gym does not provide anything in and of itself. Rather it has the broader image of a tool for learning things, through play, that might be useful in life.

- This is especially true when you use the English word "play" translated from the Japanese word, as it has a wider meaning.

YS: That's correct. I believe that the wider meaning of a playground is perhaps what I was seeking as I became a member of society. Perhaps I was dealing with something personal, small, and incomparable, rather than some great ideal shared by everyone.

NK: It was also important that the Aerial Being this time was a little different than the usual pose. Its hands were placed behind its head.

YS: It's the pose of an afternoon nap. I was really into that when I created it (laughs).

NK: It appears to be a pose with a very strong message.

YS: Placing the hands behind the head is also a gesture of surrender. In other words, it is a sign saying "I won't fight." That someone can spontaneously take the pose of an afternoon nap shows that they are in a very peaceful and safe place.

NK: We could also interpret the message as being a critical one, suggesting that we live in a time where you cannot simply lie down somewhere placing your hands behind your head, leaving your belongings without paying much attention to them, even in Japan. Perhaps it is even difficult to entertain the simple thought of taking a relaxing afternoon nap. Personally, I could not help thinking about many different things when I saw this "traveler" napping.

An exhibit staring far and near

- I understand that you received various reactions from many curators of other countries, Kawakami-san.

NK: In the adjacent room was Israel's exhibit, and France's and Turkey's were across the way. Those three countries are all faced with the problems of refugees and terrorism.

The thing they all said in common was that Japan's exhibit was unique, and that it had taken a completely unexpected approach. The Israeli exhibit featured a device allowing hearing-impaired people to enjoy sound by vibration, and a prototype device for dropping three kilograms of first-aid supplies from the sky in places where natural or manmade disasters had occurred.

The Israeli curators said that it was important for design to look further into the distance while also solving the problem right in front of you, but that students studying design typically become overwhelmed with just trying to solve the problem in front of them, and this comment left an impression on me. They also praised Suzuki's exhibit, saying that it placed importance on both and tried to propose what we could do as an individual.

Suzuki-san's position in Japan's design world is also extremely unique and he has been bringing about stimulation in a variety of ways, but I felt this time that his works were having the same effect on experts overseas as well. I believe they were able to sense his philosophy that design is like a compass that points out a path towards the future, which becomes available by awakening peoples' sensitivities.

YS: What made me happy was that the exhibitors from the other countries came to our exhibit several times. So I feel very encouraged that I was able to evoke a sympathetic reaction in other creators.

NK: The Turkish exhibit was also ambitious. It was entitled The Wish Machine, which was an installation of plastic tubes in the gallery in the shape of a hexagonal tunnel, into which individual wishes written on paper were inserted. These sheets of paper were then carried out of the room by air pressure. The tubes were installed throughout the corridors of Somerset House, so there was a constant procession of wishes. The fact that Turkey created this as a country faced with the refugee problem and an unstable political situation gave me food for thought.

YS: I felt a sense of the challenge presented by the fact that the Biennale was an exhibition. I imagine that many people are unable to write down their true wishes at an event like the Biennale. I myself just wrote down "Hello" to start out, because I was more interested at first in testing the mechanical function of the machine. I think it is very important to go beyond simply communicating your concept, and ensure that your exhibit does not simply end up being a demonstration for the attendees.

- I believe the only place that we can sincerely think about things is the place where we live and the place that has close connections with our thinking. Appointing a space in a manner that accords a sense of neighborhood or of a living space gives rise to natural posture and gestures. Perhaps the common element in your works is that those types of effects are also designed into the structures.

YS: In a very strange coincidence, the gallery at Somerset House was almost identical to my lab at the University of Tokyo. The lab has a gallery, where there is a display platform made by stacking acrylic cases. When the advisors came to my lab, they said that I should just bring that space to London as is. So I came up with the idea of attaching a handle to the acrylic cases to give the impression of luggage. While I chose a different size of acrylic case to use for the London exhibit, anyone who had seen both places would feel that I had just moved my lab to London.

NK: That was another way in which his method of representation was exhibited. We could also understand that utopia is actually the place where we normally are. The exhibit was very typical of Suzuki-san's style.

Altering the display cases in Suzuki's lab to look like luggage.

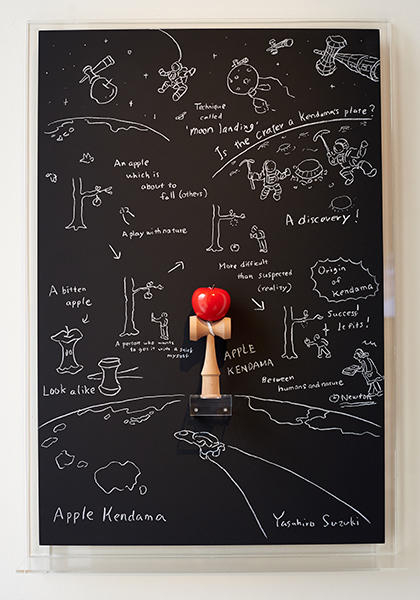

These texts about a Japanese wooden toy kendama and Suzuki's work Apple Kendama were written in English for the London Design Biennale 2016.

The nature of education in the future

- This next question is for Suzuki-san. I heard that two children from the ROCKET Project (a joint project by the University of Tokyo's Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology and the Nippon Foundation) participated in creating some of the works for this exhibit. The project seeks new opportunities for learning for children less able to adjust to normal school life. What did you think about that initiative?

YS: It was a very new experience for me as it was the first time for children to participate in my work. As I observed the children, I had the sense that there was a similar child inside of me, so I had a sense of familiarity. For example, I myself was not very good at Japanese or math, and that is why I developed a need to make things. I believe the viewpoints that one cultivates from having something that they are not very good at hint at shifting their understanding.

As you know, the standard format of education is to teach knowledge disconnected from experience. For the general public, that is probably unavoidable to some extent, but I guess having few options is very constraining. Just as I became aware of certain things only through the act of creating my own artwork, there are many things that can only be discovered by trying different approaches or taking different routes, and this discovery is very important because everyone is different. I was able to reconfirm this by observing the children participating in the ROCKET Project.

NK: The two boys, T and N, came to London with us. That was actually an amazing thing, for children to refuse to go to school to get on an airplane and go all the way to London. It is very important in design as well for people across different generations to participate in the same activities together, and I believe the ROCKET Project provides that opportunity.

YS: It's like moss.

- Moss?

YS: As I walk around my neighborhood, moss always grabs my attention. Moss needs moisture to grow, but it also seems to grow naturally in unexpected places where there is plenty of direct sunlight. That means there is moisture and water there even though people are not aware of it. So, we can see certain characteristics of the places from moss.

When an art project is thriving in a community, there will be many projects, the core of which is often how to have people participate. But "we create a foundation like this to organize the project as we want" does not sit well with me. That is backed up by the desire to produce results in a very short period of time, but that is actually something that can't be controlled. It is the outcome born of an accidental meeting of talents and interests of unknown origin that gives rise to something that is moving, no matter how small.

It was actually a complete accident that it was T and N who participated from the ROCKET Project. I believe the growth of moss in our surroundings is an example of this type of randomness or of a sense of time that involves a certain amount of patience. It is a better example than the growth of a tree, because that would take longer than a human lifetime (laughs).

Designers are normally called on to do their work according to a schedule and produce the promised output, but in an extreme case, it may become important to be sensitive to changes or the possibility of arising later in some other form even if the output isn't produced right away.

I believe that, in important situations, people have sensibility you can only call an instinct for integrating the part with the whole. My project to connect neighborhood and globe, which I have worked on since 2001, is still only in the early stages, but many unexpected relationships have been born in the process of making that concept a reality.

As the flow of information continues to increase, I believe design will become an even more important concept to help people to be grateful for the ground they stand on and to live in diversity on this planet. When things unexplainable by scientific analysis or unexpected phenomena that exceed intent are incorporated into design, I believe that the attitude of and sensitivity towards accepting nature (or others) that has been cultivated in Japan will be leveraged widely as a foundation for design.

My trip to the London Design Biennale, with luggage in hand, luggage embodying the Neighborhood Globe that connects the present time and place with that which is universal, was a valuable opportunity to expand my viewpoint from my neighborhood to the world.

Interviewer/Text: Taisuke Shimanuki

Interview photos: Yuta Hinohara

Yasuhiro Suzuki

Yasuhiro Suzuki was born in 1979 in Shizuoka, Japan. He graduated from Department of Design, Tokyo Zokei University in 2001 and is currently an associate professor at Scenography, Display and Fashion Design of Musashino Art University, and a visiting researcher at the University of Tokyo's Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology (Nakamura Lab). Using unexpected everyday discovery as a motif, he produces works, which remind us of our memories and arouse our empathy. Besides taking part in exhibitions held at Japan and abroad, he tackles actively public space projects and collaborations with companies and university research institutions. His major solo exhibitions include Neighborhood Globe (Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito, 2014). He received a Mainichi Design Award in 2014. The collection of his work Neighborhood Globe, was published by Seigensha Art Publishing in 2015. The exhibition Spontaneous Garden (August 5, 2017-February 25, 2018) will be held at the Hakone Open-Air Museum.

【Official Website】http://www.mabataki.com/en/

Noriko Kawakami

Noriko Kawakami is a design journalist and Associate Director of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT.

She has worked as a freelance journalist since 1994 after working in the editorial department of the design magazine AXIS. She also participated in the Italy-Japan design projects at the Domus Academy Research Center as Editorial Director from 1994 to 1996. In addition to becoming involved in planning at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT from 2007, she has worked as a curator for exhibitions of Japanese design, and she has recently served as a joint curator for Japan Design Today 100 (currently on international tour since 2014).

Related Articles

Back Issues

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.10.24 Inner Diversity <2> …

- 2022.10. 5 Living Together with…

- 2022.6.13 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 3 The 48th Japan Found…