Rivals Aspiring for a Common Future

Ryo Yamazaki (CEO of studio-L, Professor at the Tohoku University of Art and Design)

The Japan Foundation dispatched community designer Ryo Yamazaki to Jakarta, Medan, and Surabaya in Indonesia, and organized a series of lectures and workshops for Indonesian experts, students, and residents with the objective of exploring possibilities for cooperation with local communities through conveying and sharing the role of communities and the importance of community building. The project was implemented parallel to the holding of the traveling exhibition How Did Architects Respond Immediately after 3/11-The Great East Japan Earthquake in these three cities. Upon returning to Japan, Mr. Yamazaki contributed an article about the significance of his visit to Indonesia.

Introducing community design to Indonesia

In the last week of March, I traveled to Indonesia for the first time in my life as part of a project organized by the Japan Foundation. This invitation was an extremely gratifying opportunity to introduce the methodology of community design, which is an as-yet-unknown concept even in Japan, to the Indonesian public.

Community design is to help local people participate in solving problems in their neighborhoods. The first step in community design is to study the neighborhood, listen to the ideas and opinions of its residents, and have them gather and hold discussions. Through such discussions, they share various problems in the area, explore possible measures to solve them, and then put the solutions, which they have agreed into practice. Our role is to support this process through our skill as designers. In other words, it is a job similar to community development, but there are also many projects on a smaller scale oriented to specific facilities, such as department stores, hospitals, parks or temples.

During my one-week stay in Indonesia, I visited Jakarta, Medan, and Surabaya. My overall impression from the trip is that Indonesia is a hot and densely populated country. I was particularly noticed by high proportion of young people. In Japan, I feel like breaking into a smile when I see a baby on the street, but in Indonesia there were so many babies everywhere that I can't do at each one of them. From this perspective alone, it is obvious that Indonesia is a "young country."

Pasar Santa in Jakarta

In Jakarta, I was greatly impressed by the Pasar Santa. The lower two floors of the facility function as an ordinary market, but on the top floor it is full of stylish shops run by young creators.

Shops of young creators on the top floor of Pasar Santa

The place reminded me of the Chungnyun Mall that I visited in Jeonju, South Korea. In general principle, the lower floors of a market facility are better for business. That is why longtime shops remain on the lower floors, while shops that occupy the upper floors gradually vacate their stalls. In both Pasar Santa and Chungnyun Mall, young people open creative shops on such vacated stalls. At first, the rent is low, but as the popularity of the market increases, rent gradually goes up. I saw the same situation in Pasar Santa. It is said that there are more than 100 young people waiting to open shops at the market. Youthful energy overflows in this young country. On the other hand, it was also very interesting for me to observe the people who worked on the lower floors of the market. Unlike the young creators, the people who have worked at the market for many years were much more relaxed. Some took naps on cardboard boxes or on top of their tables.

Taking a nap on a stack of cardboard boxes on the ground floor of Pasar Santa

Another merchant taking a nap on top of his table on the ground floor of Pasar Santa

The new challenges which young people face on the top floor look positive, but the relaxed attitude to work seen on the lower floors is also quite appealing. The fact that these two different approaches to trade and business coexist on neighboring floors in the same building is another fascinating feature of Pasar Santa.

Project for preservation of historic buildings in Medan

One of the things that impressed me the most in Medan was the project for the preservation of historic buildings. In Japan, efforts to preserve historic buildings involve a complicated negotiation process with the landowner, who may wish to demolish it. If the land happens to be owned by a city, the preservation efforts might be obstructed by issues such as the building's vulnerability to seismic activity, or existing unmodifiable plan to build a new public facility on the same lot. In cases when the owner is a private developer, preservation efforts have to contend with the costs of retrofitting the old building to withstand earthquakes and preserving it as a low-rise structure, as well as with potential profits that may occur if an entirely new facility is not built on the same lot. In Medan, however, eviction of illegal occupants is an issue when they try to preserve historic buildings. At the field trip, the students who served as our guides demonstrated great vigilance. Blue flags put up by organizations that occupy old buildings lined the perimeter of the building sites, and markets for stolen items were opened in front of them.

A historic building in Medan: the building is inhabited by squatters and a market for stolen property operating outside

Left: Singing voices are heard from the inside of an illegally occupied building

Right: Market in an area of historic buildings

A built-up area in Medan

First, buildings must be repossessed from such illegal occupants, then they must be renovated, and finally, it is necessary to consider how these buildings will be used. Unless their future utilization is clearly and specifically planned, squatters will eventually reappear and once again make themselves at home in the renovated building.

An example of preservation efforts in which a water tower was converted into an observation tower

Ayorek in Surabaya

In Surabaya, I was impressed by the initiative of local young people to renovate an old residential building and re-open it as a library.

Left: The library run by Ayorek

Right: The interior of the library

Through an organization called Ayorek, young people explore the city of Surabaya from their unique perspective, and engage in activities to share the appeal of the city with the rest of Indonesia and to the world. Their library provides access to many books, and also sells publications which have been created independently by Ayorek. A broad variety of experts in fields, such as design, photography, and editing, participate in Ayorek, providing the organization with the capacities necessary to create its own books and websites.

A book published by Ayorek

In the back of the library, there is a small space used as a venue for "mini-lectures." The members of Ayorek cooperate with other citizen groups which are active in Surabaya, participate in joint projects, and design the websites of other organizations. Almost all members of Ayorek are in their 20s. I am really looking forward to the initiatives they will take on in the future. When we were operating the predecessor of studio-L, a voluntary organization called "Seikatsu Studio," we had no idea that one day we would establish a community design office and would successfully convert our activities into a real job. Today, Ayorek is pondering whether it should, and actually could, turn its activities into an organized business. I think that they should take their time pondering these issues. The more thorough their pondering is, the more certain and steady their future will be.

Lectures and workshops

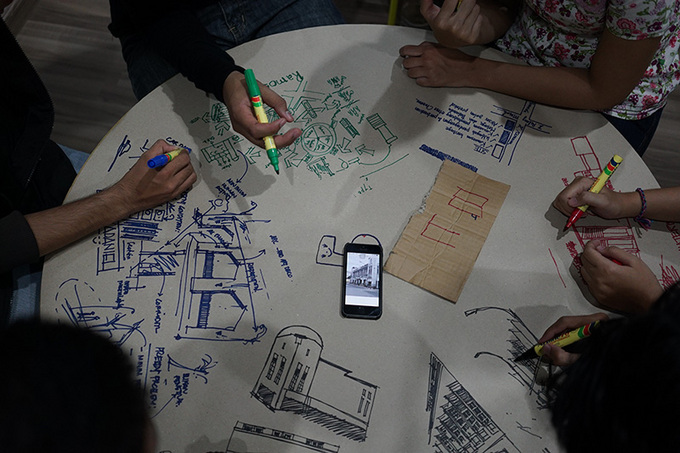

I delivered lectures and conducted workshops at universities in Jakarta, Medan, and Surabaya. I changed the content of my lectures based on the things I saw and learned at respective cities. This must have been very troublesome for my interpreter Mr. Matsui. Nevertheless, he had a good understanding of our activities and conveyed my words to the students in an appropriate manner. At the workshops, we used tabletops made of cardboard, and the participants, organized into groups, placed them on their laps and used them as tables.

Workshop at Pelita Harapan University in Jakarta

This arrangement helped forge close bonds among the members of each group. Since there were many architecture students at each of the universities that hosted our workshops, I decided to have them express their ideas not through words but through diagrams.

Workshop at the Sumatera Utara University in Medan

At each workshop, I decided to have the participants discuss issues specific to their region. In Jakarta, the theme was "problems in urban living and their solution." In Medan, it was "issues related to preservation of historic buildings and new ways to utilize renovated buildings." In Surabaya, the theme was "problems in university life and stall designs to solve these problems." When the points of discussion were expressed through diagrams, even I could comprehend, to a degree, the content of the drawings despite the fact that I do not understand Indonesian.

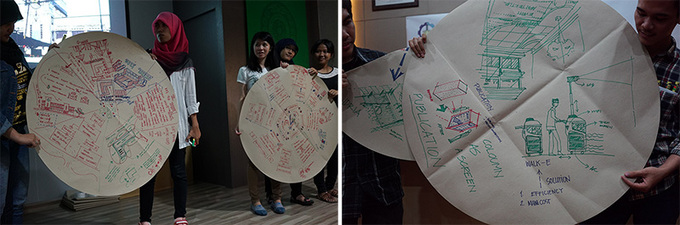

Presentation in Jakarta

Left: Presentation in Medan

Right: Content of the presentation at the Surabaya Institute of Technology. A unique stall design proposed by the participants

The ideas and the positive attitude of the students filled me with hope for the future of this young country.

Rivals that mutually inspire each other

I have often heard that Indonesian cities today look very much like Japan back in the 1970s. Indeed, almost all roads outside the central urban areas are unpaved, and the building of sewerage systems has not advanced much. Also, traffic congestion is a grave problem and child labor is often used. This reality certainly explains why Indonesia is said to resemble Japan in the 1970s. At the same time, however, Indonesians use smartphones and are obtained information from the Internet. In the future, Indonesia is not likely to follow the same path that brought Japan to modernity. We should already be able to aspire for a common future. Over the next 40 years, both Indonesia and Japan will advance toward the ideal future from their respective positions. The shops of the creators in Jakarta, the projects for renovation of historic buildings in Medan, and the initiatives implemented by Ayorek in Surabaya are basically the same as the activities undertaken by young people in Japan today. By sharing experience and knowledge, and by mutually inspiring each other, we shall advance, step by step, to the social norms that best suit our respective countries. I believe that in this process, the perception of time of the people who take their afternoon naps at the markets of Jakarta and the resourcefulness of the people who illegally occupy historic buildings in Medan will provide helpful hints for our future lifestyle.

Going forward, we should compete with the young people of Indonesia not from the position of citizens of an advanced country, but as people who develop activities in a country that aspires for a common future.

Ryo Yamazaki

Ryo Yamazaki

Ryo Yamazaki, CEO of studio-L, was born in 1973 in Aichi Prefecture. He studied the Osaka Prefecture University Graduate School and the University of Tokyo Graduate School, and obtained his Doctorate in Engineering. After working for an architecture and landscape design company, he established studio-L in 2005 and got involved in community design to assist local people in solving problems faced by their neighborhoods. He was engaged in numerous projects, including community-building workshops, formulation of comprehensive plans through community participation, and citizen participation-type park management. He is also a professor at the Tohoku University of Art And Design (Director of the Department of Community Design), and a guest professor of Keio University.

He received the Good Design Award for the Comprehensive Development Plan of Ama, the studio-L IGA office, and Setouchi Shimanowa 2014, and the Kids Design Award for the Mother-and-Baby Notebook.

His publications include Komyuniti Dezain [Community Design] (Gakugei Publishing Company, received the Real Estate Companies Association of Japan Award), Komuniti Dezain no Jidai [The Era of Community Design] (Chuko Shinsho), Sosharu Dezain Atorasu [Social Design Atlas] (Kajima Institute Publishing Company), and Machi no Kofukuron [Happiness Theory for the Local Area] (NHK Publishing).

Back Issues

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.10.24 Inner Diversity <2> …

- 2022.10. 5 Living Together with…

- 2022.6.13 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 3 The 48th Japan Found…