Young Artists Visit the United States: Reactions toward their Initiatives to Popularize Japanese Contemporary Art on a Global Scale

Shiho Kagabu

Gaetan Kubo

Yasuka Goto

Mariko Tomomasa

Yuta Nakamura

Moderator: Yukie Kamiya (Chief Curator, the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art)

As part of the KAKEHASHI Project - The Bridge for Tomorrow, U.S. Youth Exchange Program, five young Japanese artists visited New York and Los Angeles in November 2014. Over a period of seven days, they went to local art museums, galleries, and art studios, and engaged in efforts to popularize Japanese contemporary art and modern Japanese culture through presentations of their own works. The group included participants at the VOCA (Vision of Contemporary Art) exhibition, which is considered a gateway to success in the field of contemporary art, and a finalist of the Taro Okamoto Award for Contemporary Art. From this perspective, these artists are expected to lead the next generation, so the impressions and feedback they received from the exchange with young U.S. artists and relevant parties in the art world and from the presentation of their own works is a matter of great interest. After their return to Japan, we invited them for a talk moderated by Yukie Kamiya, Chief Curator of the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art and advisor to the KAKEHASHI Project, at which they shared their impressions and the challenges they face.

Presentation at Japan Society

Difficulties in popularizing Japanese culture in New York, home of people with diverse backgrounds, and discussion of a different quality

Kamiya: I believe this dispatch project has been extremely productive and fulfilling for all of you. Could you please share the most memorable moments of it and your impressions of the tour?

Nakamura: I was impressed by the outspoken opinions we received from the audience at our presentations at Japan Society. We conducted two presentations--a rehearsal and the actual one--at a theatre-like venue with a capacity of 260 people. In conveying the appeal of Japanese craft culture, I did not simply present the field of crafts from the perspective of traditional techniques and materials, but also spoke about creation and research that use tiles and ceramic pieces from the perspective of "craft culture associated with folk customs and architecture". At the Q&A session at the presentation, I was asked why I, an artist, had a PhD degree. My response was that I believed that for an artist it is important to convey the culture of crafts not simply from the perspective of creation, but also from a research perspective. These kinds of questions made me consider the difference in the image of artists in the U.S. and in Japan, and the ways to link creation with research in the future.

Presentation at Japan Society

Kubo: I spoke with people of various ethnic backgrounds at the networking event after the presentation. In the conversations, I shared my desire to create works that stimulate the intersection of majorities and minorities. One person responded that he could identify with this idea because, despite being born and raised in the U.S., he has often been rejected and excluded as a minority due to the fact that his parents were immigrants. This opinion was countered by an elderly woman of Japanese descent who said that she has never been treated as a foreigner in New York. This made me think about how to define "minority" in a place where people have such wide-ranging circumstances, and also question the significance of displaying my works. I also had the impression that during the open house session, the exhibition attracted more people who are interested in Japanese culture rather than art connoisseurs. New York is a melting pot of art traditions and trends from all over the world. Thinking about ways to attract the attention of artistic circles in New York, a city that draws art trends from all over the world, made me realize how difficult it is to popularize art here.

Kamiya: By that do you mean it is difficult to attract attention in aspects other than the purely artistic context?

Kubo: Right. It is difficult to adeptly link the interest in Japanese culture in general with a more specific interest in Japanese contemporary art.

Kagabu: Many of the people who attended our presentations at Japan Society harbored the impression that anime and otaku culture are the representative forms of Japanese art. After listening to our presentations, many said that they enjoyed and were very interested in the presented expressive forms that differed from otaku culture. This kind of feedback made me very happy. Our visits to studios of local artists were also a very interesting experience. I was particularly impressed by the fact that the U.S. museum system was different from the Japanese. The content of the exhibitions was very rich, and the impression produced by the curators differed greatly from one art museum to the other. My impression was that art museums in New York have more freedom than art museums in Japan in organizing exhibitions, probably due to the fact that art museums in New York are financed through donations.

Kamiya: It appears that the event at Japan Society has left the strongest and most lasting impressions on all of you.

Tomomasa: I was on the receiving end of the toughest opinions expressed at the presentations held at Japan Society (laughs). I received comments on every aspect of my presentation, from the way I delivered it to my English pronunciation. There, I felt that U.S. audience expects and demands presentations to be more engaging as entertainment. Also, in Japan when artists explain their work even to an audience that is interested in art, we do it step by step, while people in New York appear always ready to listen, and are very proactive and prepared to engage in a deep discourse. For instance, they do not want long introductions and are impatient to get to the gist of the discussion. Also, they express opinions even with regard to works they have not seen.

Goto: In my case, I had prepared a presentation in which I expressed personal opinions and experiences in a manner tailored to the characteristics of the audience, so I received positive feedback from the ordinary spectators. Yet, for the art crowd my presentation apparently was not enough of a challenge. Throughout my stay in New York, I was constantly told to improve the context of my works, and I pondered over this issue for the entire week. I was told that U.S. audience is composed of people from widely diverse backgrounds, so it is a given that they can empathize with different things, and I had to make sure that I share with them some basic concepts. I realized that I was trying to proceed with my presentation without first sharing the basics.

Kamiya: Have you ever had an opportunity, here in Japan, to deliver presentations and receive feedback on them in the same manner as you did in New York?

Tomomasa: I have had experiences in Japan, too, but I feel it was very different in nature from what I experienced in New York. People in New York are used to discussions and arguments. Some of my works require explanation, and when that is new information for my audience, in Japan we seldom reach the point of discussing and arguing, while in New York many people were ready to initiate an exchange of opinions regardless of whether they understood my work or not.

Kagabu: I have frequently experienced discussions on artwork in classes at university or at artwork presentations, but in Japan it is often the case that it takes several years for some people to engage in a profound discourse. In New York, on the other hand, sometimes it takes 15 minutes for artists and art lovers to make insightful comments that in Japan would require several years. This kind of speedy feedback is extremely stress-free for me as it eliminates the need for excessive interaction. Prior to my visit to the U.S., I used to think that I had to dig deep into my cultural identity as a Japanese, but after going there I realized that this is not all that important, and I felt that people were much more interested in my stories as an individual.

Presentation at Japan Society

Left: Introduction of works at Japan Society

Right: Exchange with the audience at Japan Society

Matching the Japanese background with the global context

Kamiya: Did you feel a desire to positively respond to the inquisitiveness of the U.S. public with regard to Japan? Or did you experience a kind of uneasiness from these requests?

Nakamura:

At the briefing with Laura Hoptman at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, she spoke of the importance of context, making references to Japanese artists. Through this dispatch, I learned to positively consider the importance of the Japanese domestic context of crafts on a global scale, including the U.S. Also, as seen in Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde, an exhibition organized by MoMA in 2012, U.S. public is interested in the process of revisiting the context of Japanese postwar art in terms of the relationship with its environment.

Yuta Nakamura explains his works to Laura Hoptman of MoMA

Kubo: I realize that this is slightly tangential to the question that you asked, but I have two backgrounds--a Japanese one and a French one--so the works of two artists, which I saw in New York, were very thought-provoking. These two artists are Chris Ofili, whose solo exhibition was held at the New Museum, and Rashid Johnson, whose studio we visited as part of the program. Both are second-generation immigrants from Africa and I was impressed by the fact that they use materials originating in Africa in their works in order to express their roots. In my case, I have never lived in France, and until now I have not been very aware of my French background, so I felt the necessity to reexamine the way I, a person born and raised in Japan, define the heritage received from my mother.

Kagabu: I feel that becoming overly conscious of the fact that I was born and raised in Japan is not the best approach from the perspective of the expansive nature of my works. The important thing when presenting my works abroad is to contemplate in depth the importance of my Japanese background and the way it influences the creative process. Also, I realized that it is better to develop the ability to masterfully convey what makes me interesting as an artist.

Tomomasa: I developed a good understanding of why it is necessary for me to consider my attitude as a Japanese and the context of the way I perceive Japan, but I worry whether I will be able to objectively consider Japan from the perspective of an artist who will continue to live here in the future. The United States is a country created by people from various backgrounds who live together. Conversely, Japan is so homogenous that we believe we do not need words to perfectly convey our ideas and intentions. From this perspective, there are significant differences between the situation in the U.S. and Japan, so I am confused as to what is the best approach.

Kamiya: This is a rather difficult point, isn't it? We can consider the concepts of our own art, but as we are situated in the culture where we were born and raised, we find it difficult to objectively examine the contextual part of it, or in other words, how to position it in that culture.

Goto: Rather than getting bogged down in detailed explanations about one's works in order to gain understanding, it would be so much better if there was something like an equation. I still cannot express what I mean very well, but I wish that works of art featured an equation-like sensitivity with which all human beings could empathize. On our free research day, I visited the exhibition of Henri Matisse at MoMA. The venue was packed with visitors. To me, this enormous popularity suggests that the works of Matisse contain numerous such equation-like features that speak to each and every one of us.

Kamiya: I see. You want to give the audience a broad leeway to interpret your works, but at the same time remain true to your core ideas and express them in a solid manner.

Visiting the studio of Rashid Johnson

Discoveries from the visit to the U.S. leading to new discoveries

Kamiya: Based on your experience in the United States, are there any new challenges that you wish to take up?

Goto: I have the feeling that my perspective on things has been changing little by little after returning to Japan. My awareness of context as a Japanese gradually narrows my perspective down to a search of my own roots, but I feel that eventually this will lead to the discovery of some common term as a human being, or, as I just said, an equation.

Kubo: This experience inspired me to see other countries, and immediately after returning from the U.S., I visited Paris and London. There, I encountered many Japanese artists who are virtually unknown in Japan's art circles, and felt the power of connections inherent to local people, which they possessed. I do not by any means suggest that it is necessary to reside there permanently. I felt, however, that in the modern age, once a connection is established, it remains strong even if the people who have established it are separated physically, so I would like to increase the hubs of my activities across the world while establishing Japan as my home base.

Appreciating works of art at the New Museum

Nakamura: I am fascinated by the act of translating between cultures. When translating through words, sometimes errors may occur, but to me it feels more interesting and enjoyable to proactively incorporate such mistakes in the process of artistic creation. For instance, potters in the late Edo period emulated the works of potters from previous generations. Their work is called "copy," but it is not simple "copying" as the works reflect a unique "translation" of the ideas of the original masters. During our trip to the U.S., we discovered different kinds of tiles as we walked down the streets. Tiles appear similar regardless of the country, but a careful examination reveals that their size, the way they are placed, and their maintenance and repair are different. In other words, tiles are a global material, but at the same time their "translation" varies depending on the region. In the future, I intend to turn my attention to such subtle differences in intercultural translation.

Tomomasa: For me, the visit to the U.S. came immediately after my return from Burkina Faso in Africa, so I felt a bit confused. In Africa, I stayed in a small village, without electricity, where laundry was done in the river and people relieved themselves in the open. I went there with the intention to conduct a conventional exhibition, the type at which artists show their works and an audience comes to appreciate them, but I realized that it was not right to force my art onto people who do not have the custom of observing art. That is why I changed the format of the so-called "exhibition" into something that resembled a presentation or a festival, art forms that are much more familiar to the African people, and put on a performance through which they observed my works. In New York, I was well-prepared, and the environment to display works of art was fully established. I felt a bit surprised. In New York I was perceived as an Asian, a national of a country that maintains its traditions and at the same time has achieved modernization. Most of the people I met in Africa, however, did not know anything about Japan, and since I was wearing Western clothes, they saw me as a bearer of Western things. My experience in Africa helped me realize that the results of my work are a Western type of art. After going to New York, however, I felt that my art is in fact an imitation of Western art and perhaps it is essentially Japanese and Asian in its nature. I felt like I was torn between the two.

Kamiya: You probably felt swayed by the fact that the way you are perceived and positioned changes depending on where you are.

Tomomasa: Indeed. One of the things I thought I should do is learning sumo wrestling forms, for instance. In Africa, I was asked to perform a dance, so I tried imitating some simple sumo forms. The response of the audience was extremely enthusiastic (laughs). The fact of the matter is that the first thing that came to my confused mind after a sudden request to perform was a traditional Japanese sport. In New York, too, when I was trying to convey a concept that the audience found hard to understand, all I had to do to gain their understanding was throw in a reference to traditional Japanese culture.

Kamiya: In that sense, we feel the overwhelming power of traditions in their ability to make a diverse impact on completely different cultures.

Kagabu: After returning to Japan, I felt the desire to create works that were detached from myself, works that could go to another country without me or that would continue to exist independently even if I died. I am currently raising a family, so my scope of activities is somewhat limited, but nevertheless I continue creating works of art. I believe that even works that I have created without leaving the house could inspire a feeling of empathy in mothers in faraway countries or in people of the same generation who live in a completely different environment. I would like to find a better way to showcase my works in different countries. In New York, art is omnipresent and I had opportunities to encounter people that I usually cannot meet in my everyday life. I thought that New York was the best and that I had no choice but to move there. After returning to Japan, however, I had an exhibition in Kichijoji, and realized that in Kichijoji, like in New York, there is a wide variety of food, art museums, galleries, and fashion. This made me think that Kichijoji is no different from New York. Nevertheless, I have never felt very fortunate to be working in such an environment, maybe because the quality of the displayed works was not very good. Still, as a nation, Japanese people visit a lot of art museums on a global scale, and art is ubiquitous in our cities. I have often pondered why the environment in Japan feels so bland and unimaginative. The conclusion I reached is that we must make efforts to improve the quality of our own works.

With Manhattan in the background

Kamiya: It appears that the one-week visit to the United States has brought many new discoveries for all of you. Listening to your stories, I was reminded of a line from the book Representations of the Intellectual by Edward W. Said, in which the author suggests that an intellectual should be not like Robinson Crusoe but more like Marco Polo. An intellectual is like a shipwrecked person who learns how to live in a certain sense with the land, not on it, not like Robinson Crusoe whose goal is to colonize his little island, but more like Marco Polo, who has visited different countries and experienced things unlike anything someone has ever seen before, and whose sense of the marvelous and respect for the foreign culture never fail him. Marco Polo is always a traveler, not a conqueror or raider. He is a provisional guest who goes to foreign lands empty-handed and learns about them. With this kind of attitude, he is at home anywhere he goes. Just like Marco Polo, if you visit various places with an open mind and make new discoveries, you will feel at home there, and these discoveries will inspire you to create new works of art. That is why I believe you should allow yourselves to drift more. Through this visit to the U.S. you did not think "I must become more Japanese," but felt that you should discover various things. This means that the one week you spend in the U.S. was a truly wonderful experience. I cannot wait to see how this experience will change you, what kind of Marco Polo you will become, and how your sense of the marvelous will help you turn new destinations of creation and learning into your home.

From left to right: Shiho Kagabu, Yuta Nakamura, Gaetan Kubo, Yukie Kamiya, Mariko Tomomasa, and Yasuka Goto

(Editor: Ayako Tomokawa)

【Reference Articles】

Feature Story: Design that Connects the World - Young Designers Visit the United States

Contributed Article: The Next Leap - Report on Exchange Among Young Fashion Creators in New York

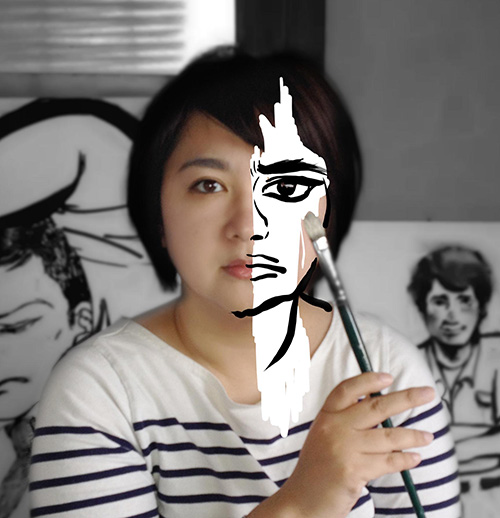

Shiho Kagabu

Shiho Kagabu

Shiho Kagabu was born in 1981 in Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture. She obtained a BA in Art and Design from Bunka Women's University (current Bunka Gakuin University) in 2004, a BFA in Sculpture from Tama Art University in 2005, and an MFA in Sculpture from the same university. Her major recent solo exhibitions include Open Studio Program No. 51 (Fuchu Art Museum, 2010), Yoki-Nemuri-no-Ie (JIKKA, 2013), and Yoki-Mezame-no-Ie (NADiff a/p/a/r/t, 2013). In 2013, she participated in the group exhibition Artist File 2013: The NACT Annual Show of Contemporary Art (The National Art Center, Tokyo).

![]()

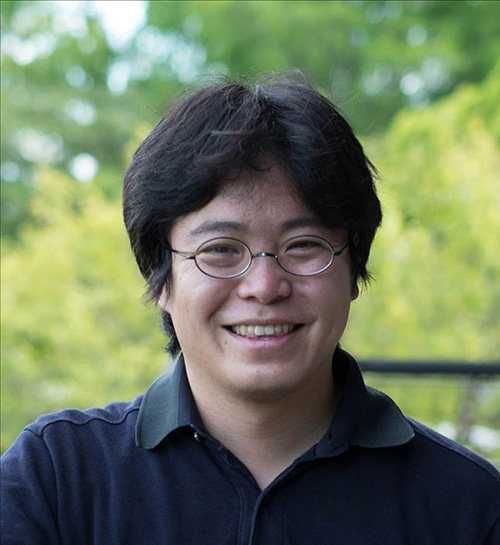

Gaetan Kubo

Gaetan Kubo

Gaetan Kubo was born in 1988 in Tokyo. He graduated from the Department of Intermedia Art at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts in 2011, and obtained a Master's degree in Intermedia Art from the Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts in 2013. Currently, he is based in Tokyo and Ibaraki. His major recent solo exhibitions include Madness, Civilisation and I (2012) and Hysterical Complex (2013), both presented at Kodama Gallery. He has also participated in group exhibitions, such as the Gunma Biennale for Young Artists (The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma, 2012, 2015), and The "Bagic" (Haishakkei, 2014).

![]()

Yasuka Goto

Yasuka Goto

Yasuka Goto was born in 1982 in Hiroshima Prefecture and lives in Hiroshima Prefecture. She graduated from the Oil Painting Course, Department of Fine Arts at the Faculty of Art of Kyoto Seika University in 2004. Her major recent solo exhibitions include Yasuka Goto Exhibition (Yachiyonooka Museum of Art, 2012), Ango Mosaku (Dai-Ichi Life Gallery, 2012), and Art Stage Singapore (Marina Bay Sands, Singapore, 2013). She has also participated in group exhibitions such as VOCA 2011, The Allure of the Collection (the National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2012), and Minato-no Monogatari (Creative Center OSAKA, 2013). Her works are part of the collections of the National Museum of Art, Osaka and the Dai-ichi Life Insurance Company.

![]()

Mariko Tomomasa

Mariko Tomomasa

Mariko Tomomasa was born in 1981 in Saitama Prefecture. She graduated from the Oil Painting Course, Department of Painting, Faculty of Fine Arts at the Tokyo University of the Arts in 2004. She received her MA and PhD in Oil Painting from the Graduate School of Fine Arts at the Tokyo University of the Arts in 2007 and 2012, respectively. Her major recent solo exhibitions include Trying Not to Be Too Close - Have a meal with Father (TALION GALLERY, 2015), CRITERIUM85 Mariko Tomomasa - Waodori (Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito, 2012), and Have a Meal with Father (Treasure Hill Artist Village, Taiwan, 2013). She has also participated in group exhibitions, such as Between art and science 2014 (IRFAK OASIS, Burkina Faso/Citta della Scienza, Italy, 2014), VOCA 2013 - Artists on New Plain (The Ueno Royal Museum, 2013), and TOKYO STORY 2014 (Tokyo Wonder Site). In 2013, she was selected for a VOCA Exhibition.

![]()

Yuta Nakamura

Yuta Nakamura

Yuta Nakamura was born in Tokyo in 1983. He graduated from the Faculty of Arts (Ceramics) of Kyoto Seika University (BA) in 2005. He received his MA and PhD from the Graduate School of Arts of Kyoto Seika University in 2007 and 2011, respectively. Currently he works as a part-time lecturer at Kyoto Seika University and Kyoto University of Art and Design. His major recent exhibitions include Roppongi Crossing 2013 / Out of Doubt...in pursuit of future landscape (Mori Art Museum, 2013), and Tiles, Hokora and Tourism (Gallery PARC, 2014).

![]()

Moderator: Yukie Kamiya

Moderator: Yukie Kamiya

Chief Curator of the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. Yukie Kamiya was born in Kanagawa Prefecture. She graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Arts, and Sciences at Waseda University. After serving as Adjunct Curator at the New Museum in New York, she assumed her current position in 2007. Her major exhibition projects include solo exhibitions of Cai Guo-Qiang, Tsuyoshi Ozawa, Martin Creed, Tadasu Takamine, Suh Do Ho, and Simon Starling (all organized at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art), Re: Quest - Japanese Contemporary Art since the 1970s (Museum of Art, Seoul National University, 2013), and other joint exhibitions. She received the Western Art Promotion Foundation Academic Award in 2011 and serves as adviser to Yokohama Triennale 2014, Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015, and Asia Art Archive (Hong Kong). She co-authored several books including Creamier - Contemporary Art in Culture (Phaidon, 2010).

Keywords

- Anime/Manga

- Handicraft

- Arts/Contemporary Arts

- Transboundary/Study Abroad/Travel

- Japan

- United States

- Burkina Faso

- KAKEHASHI Project - The Bridge for Tomorrow

- VOCA (Vision of Contemporary Art) exhibition

- Taro Okamoto Award for Contemporary Art

- Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art

- New York

- Los Angeles

- Japan Society

- Otaku

- New York Museum of Modern Art

- MoMA

- Laura Hoptman

- New Museum

- Chris Ofili

- Rashid Johnson

- Henri Matisse

- Edward W. Said

- Robinson Crusoe

- Marco Polo

Back Issues

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.10.24 Inner Diversity <2> …

- 2022.10. 5 Living Together with…

- 2022.6.13 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 3 The 48th Japan Found…