Indian Contemporary Dance--the Outlook in Chennai, Mumbai and New Delhi

Daisuke Muto

Dance critic

Ever since I encountered the world of Asian contemporary dance in 2005 or thereabouts, I had been eager to visit India.

Speaking of Indian contemporary dance, the most well-known enterprise in international circles must be the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts based in Bangalore. The Attakkalari Repertory Dance Company, under the leadership of its artistic director Jayachandran Palazhy, has toured widely around the world and has succeeded in establishing itself as the organizer of an annual festival in their home city. In January 2013, I was invited to speak for the first time at the festival, which became an occasion for numerous sources of inspiration, and I managed to create a network with various dance people from all around India.

Attakkalari gives demonstrations at schools in their Education Outreach Programme (Photo: Prasad)

A scene from Attakkalari's Young Choreographer's Platform project (Photo: Manikantan)

(Left) Attakkalari's new production "AadhaaraChakra - A dancelogue" (Courtesy of Attakkalari)

(Right) A lighting design workshop at Attakkalari (Photo: Lekha Naidu)

Six months later, I had the great fortune to be invited by the Japan Foundation, New Delhi to make a second visit to India. Relying on my newly-made contacts, I was able to visit three cities--Chennai, Mumbai and New Delhi. Based on that experience, I would like to give a brief report on the contemporary dance scene in India.

Chennai--a city being vibrant with the history of dance

During the years of the British Empire, traditional dance was once on the ebb, but the 1930s saw its revival and the foundations of classical Indian dance were established. And then in the 1980s, the genre of contemporary dance, which went beyond traditional and classical dance, began to evolve.

This trend is most noticeable in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, where the flow from traditional to modern is enacted in the capital, Chennai (formerly Madras). This is the city where Bharatanatyam, the traditional dance of the Hindu temple maidens devadasis, originated. The dance was adapted by Rukmini Devi (1904-1986) to make it a classical dance and led to the opening of her school in 1936. The city was also where Chandralekha (1928-2006) criticized Rukmini's modern version of Bharatanatyam and developed the avant-garde contemporary version of the dance. And now, Chandralekha's pupil Padmini Chettur (1970- ) is internationally active conveying her mentor's minimalism, and a new generation is emerging from Padmini's company. Thus, Chennai has been throbbing with the evolution of dance.

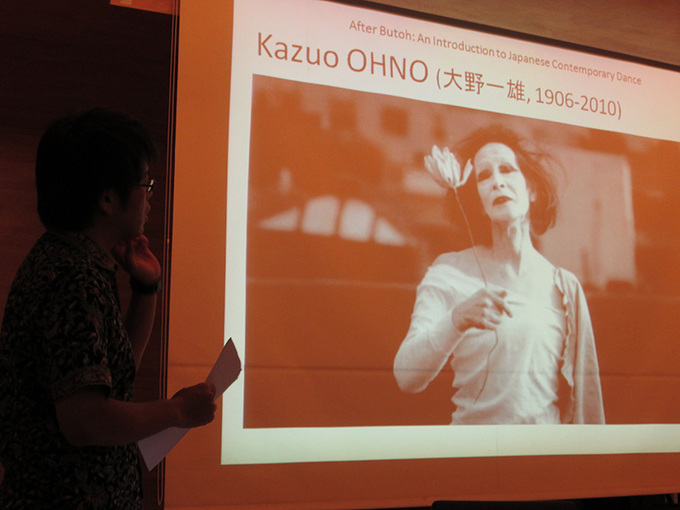

Of course, contemporary dance is still not in the mainstream, but Padmini and her protégé Preethi Athreya, who among like-minded young choreographers has formed a loosely knit network called Basement 21, have initiated various projects. Not having a permanent venue, they have been receiving the support of Alliance Française of Madras, a French government cultural body, and private galleries to stage their productions. With the backing of Basement 21 and Alliance Française, I was able to give a lecture, in Chennai, on contemporary Japanese dance. The audience included a wide range of people from various fields, such as dance, drama, stage design and music, and I felt this network growing.

After the lecture, we held a session to exchange views and discussed, among others, the connection between dance and the social framework. In India, classical dance is regarded as an important symbol of national identity, which was a stark contrast to the situation in Japan, where the genre of (contemporary) dance has developed as a denial of national identity. We asked ourselves the reasons for these differences, and how this would affect the creation of new works today. I felt that the very fact we were all Asian people made it possible to identify the many points in question.

Mumbai's movie industry playing a role as a supporter of contemporary dance

Mumbai (formerly Bombay), the largest city in India and the capital of the west coastal state of Maharashtra, has few connections to the world of dance but it is the home ground of Astad Deboo, a pioneer of contemporary dance, and is gradually becoming a new platform for emerging young dancers.

A group known as Dance Dialogues organizes performances in the city, while the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) has been holding a festival since 2011. Contemporary dance appears to be taking root in Mumbai. The moving force at Dance Dialogues is Ranjana Dave, a performer of the classical dance Odissi and a much-respected writer and journalist. She very kindly took me to the studios of young choreographers, and private classes and schools. These visits gave me a chance to view the dance milieu in this city from various angles.

Dance Dialogues also organized my lecture in Mumbai and the German cultural organ Goethe-Institut kindly offered us the venue. Thanks to advance promotion in the local newspapers, a great many people gathered on the day and they showed a genuine interest in Japanese contemporary dance, still a relatively unknown factor in India.

Mumbai, of course, is well-known for Bollywood, the centre of India's movie industry, so I was interested in the Terence Lewis Academy, a unique school in the city that teaches a combination of show and artistic dance with great success. In Mumbai, show dance has a respectable standing as a profession through the prosperity of the movie industry, so the potential for the co-existence of this type of occupation and art has become a great point of interest.

The writer introducing the Japanese dancer Kazuo Ohno in a lecture in Mumbai (Photo: Ranjana Dave)

A workshop at Dance Dialogues (Photo: Kartik Rathod)

Dancers talking about the piece they are practicing, at Dance Dialogues (Photo: Karthik Kasi)

Close global connections in New Delhi

I introduced earlier about the flourishing Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts in Bangalore. Catching up with their activities is the Gati Dance Forum in New Delhi, which creates its own works, runs a studio and organizes workshops and festivals under the directorship of Mandeep Raikhy and Anusha Lall, both choreographers and dancers. The Forum exudes vibrant energy.

I took part as a lecturer in the first week of a 10-week residency program that the Gati Dance Forum holds for young choreographers. Applicants for the program submit a proposal for a dance work they would like to create, and 10 candidates are eventually chosen. These selected people spend the duration of the program learning the techniques and styles and, by inspiring each other through a process of mutual discussion, carry it through to a finished piece. There is no fee for the participants and the operating costs are covered by subsidies gained from external benefactors.

The Gati Dance Forum does not cling to traditional dance forms, and most of the participants are eager to create pieces that have symbolic motifs or are inspired by everyday experiences, which are not necessarily based on traditional Indian culture. Many members have already studied in Europe. Anusha told me that she deplored the closed nature of the traditional dance world. This was an interesting comment because it highlighted the differences in attitude between New Delhi and Chennai, where history and the present day exist side by side.

Classes at the Gati Dance Forum in New Delhi

During my time at the residency program, I conducted choreography workshops and other related activities in addition to the lectures. I was amazed at the students' deep interest in the contents and gained an enormous amount myself from the exchanges. The program itself went on for 10 weeks, so I was not able to stay to see the results of the students' hard work, but if the Gati Dance Forum grows to a level approaching that of the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts, India will be blessed with dance centres in both the north and south, and contemporary dance in India will become a force to contend with.

My visit only lasted a little over two weeks but I was able to gather diverse views of Indian contemporary dance in Chennai, Mumbai and New Delhi. Circumstances in the three cities were different but I felt that they shared the intense enthusiasm for contemporary dance which probably came from the very fact that it was still not in the mainstream. People are eager for more exchanges within the Asian region and I have a hunch that projects involving Japan and India will be on the rise in the coming years.

Daisuke Muto

Daisuke Muto

Daisuke Muto is a dance critic and associate professor of Faculty of Literature, Gunma Prefectural Women's University. He co-authored The History of Ballet and Dance (Heibonsha, 2012) and his thesis "Kazuo Ohno's 1980" was published in the 33rd edition of the Bulletin of Gunma Prefectural Women's University in 2012. In 2009, his thesis "Strategy of Anti-Spectacle in Yvonne Rainer's Trio A" appeared in the 30th edition of the bulletin. He currently contributes to the Korean monthly dance magazine Momm and also serves as a co-curator of the Indonesian Dance Festival in Jakarta.

Keywords

- Dance

- Traditional Arts

- Film

- Japan

- India

- Chennai

- Mumbai

- New Delhi

- Contemporary Dance

- Bangalore

- Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts

- Jayachandran Palazhy

- The Japan Foundation New Delhi

- Classical Indian dance

- Bharatanatyam

- Rukmini Devi

- Chandralekha

- Padmini Chettur

- Preethi Athreya

- Basement 21

- Alliance Française

- Astad Deboo

- Dance Dialogues

- The National Centre for the Performing Arts

- NCPA

- Ranjana Dave

- Goethe-Institut

- Bollywood

- Terence Lewis Academy

- The Gati Dance Forum

- Mandeep Raikhy

- Anusha Lall

Back Issues

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.10.24 Inner Diversity <2> …

- 2022.10. 5 Living Together with…

- 2022.6.13 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 3 The 48th Japan Found…