Exploring the Essence of Design with Students in Panama, Cuba, and Costa Rica

Jin Kuramoto, Product Designer

Jo Nagasaka, Architect

The Japan Foundation hosted a series of lectures and workshops in Panama, Cuba, and Costa Rica with product designer Jin Kuramoto and architect Jo Nagasaka to introduce Japan's design and architecture and Japanese view and approach to the aesthetics of workmanship in their fields. The program was intended to inspire the participants to go back to the basic purpose of designing, which, according to Kuramoto, is "producing optimal functions or solutions which satisfy given requirements while incorporating one's ideas and sense of beauty." In Nagasaka's terms, rather than looking afar for something new, the workshops focused on re-discovering and working with objects found around us. Based on these concepts, the workshops provided opportunities for students of design and related fields to engage in creative activity through producing an original hat or a musical instrument.

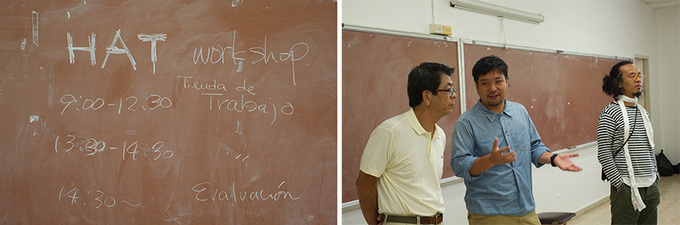

Panama: Hats made from leaves and other everyday objects

The lecture hall at Universidad Católica Santa María la Antigua in Panama City, the capital of Panama, was filled to overflowing, perhaps because it is not common that Japanese lecturers come here to talk about architecture and design. The lecture evolved into an in-depth, interactive discussion, with faculty members as well as students eagerly asking questions, which got our tour off to a great start.

(Left) Jin Kuramoto, (Right) Jo Nagasaka

The following day, we conducted a hat-making workshop. The point of this exercise was to design a hat by using materials that are easily available nearby. The students were asked to come up with ideas that meet the basic functions of a hat, such as covering the head and protecting it from the sun. Then they were to fashion their own hats using everyday objects found at home or waste materials collected from around the university premises.

Once the session began, I was astonished to see the students plunging into the hat-making without so much as a pause or hesitation. It was as if they already had sketches to work from. I also noticed that the students understood themselves very well--they knew what looked good on them. The hat they made might not be all that appealing by itself, but when the owner put it on it instantly became attractive. Many of the students used leaves and other pieces of plants for the hats, and I was impressed at how deftly they handled organic material.

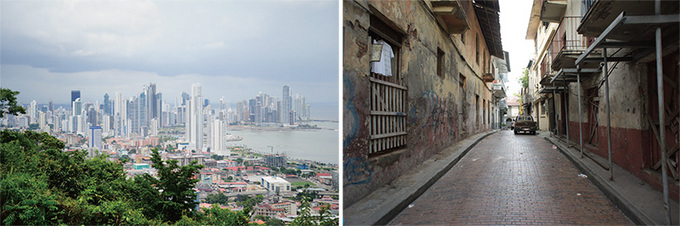

Panama is invariably associated with its canal. The canal transit tolls are an important source of revenue for the country's economy, as are the related industries generated by the vessel traffic. The hydroelectricity generated by exploiting the height differences between the canal's gates covers much of Panama's energy demand.

My impression of the country is that Panama, with its mixture of diverse cultures and numerous inconsistencies, has been blessed with the capacity to absorb new things and grow. I can imagine the country developing into Central America's economic hub in the coming years. Another notable aspect of the country is that some indigenous communities that inhabited the area before colonization continue to exist today. That Panama has supported and succeeded in preserving these cultures is apparent, considering the fact that indigenous communities in the neighboring countries like Cuba and Costa Rica have been already wiped out. The broad range of folk crafts and souvenir gifts, which were more remarkable in variety and quality than those found in other countries, reflects the richness of cultural heritage in Panama.

Cuba: Struggling with material shortages

In Cuba, our lectures on industrial design and architecture held at Instituto Superior de Diseño was followed by an open discussion on stage with students and faculty members. It was a passionate debate, encompassing everything ranging from the differences between Japanese and Cuban society to the future career possibilities of design students in Cuba.

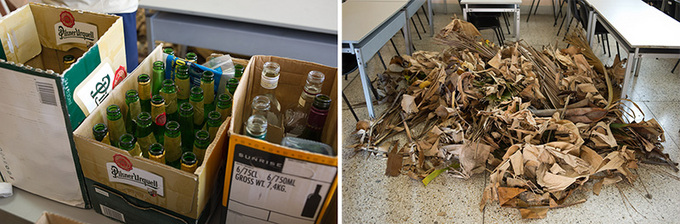

In the two workshops we held in Cuba, the participants were asked to make a musical instrument by using everyday objects. The goal was to create a device that satisfies the basic requirement as a musical instrument: to produce pleasant musical sounds when played. Unfortunately, we were faced with a lack of materials far more severe than in the other two countries we visited. Items like bottles, cardboard boxes, and pieces of wood used for packing, which have visual appeal and look suitable for the project, were in short supply. Under the circumstances, rather than working individually, we made it a team project to brainstorm and complete the task.

It took the Cuban students longer than their counterparts in Panama and Costa Rica to make a plan before beginning to put the objects together. I presume they spend more time planning because they have little opportunity to actually make things, given the shortage of goods and materials. Indeed, the assignments they had produced as part of their regular school work were largely made through computer graphics. Looking at them, I could tell they were well-trained in the basic concepts and principles of design. They seemed to struggle, however, when it came to tackling a project that deviated from the conventional notions of design--in this case, producing something with useless materials.

After completion, the students gave a presentation, playing the instruments of their own making. As you would expect, the Cubans had an amazing sense of rhythm. As soon as they receive any instrument in hand, they will play it beautifully, much better than we Japanese could do even with the best of instruments. We can only envy their talent.

We had headed towards Havana after arriving at José Martí International Airport in Cuba. An increasing number of people and buildings come into view as you approach the city. The houses are all low-rise and old, and shabby buildings line along the streets. Because there are no air conditioners, everyone has their windows and doors wide open. The interior is in plain view; and you can even see people going about their lives in their homes.

Closer to the city the buildings became taller. A large number of people were out on the streets, whether because the buildings were hot inside or because they were crowded. I spotted some men sitting around a table playing dominos, and boys playing futsal with handmade goalposts or table tennis on a table they had made themselves. Small groups of girls were busy chit-chatting among themselves. Old men would sit on a stool, all day, doing nothing in particular but gazing outside. It seemed as if the alleys were their own courtyard or lively places where people were doing whatever they liked. No one seemed alarmed at the arrival of a couple of outsiders. Open and friendly, they greeted us with smiles and, to my delight, happily posed for a picture when I raised my camera.

Blacks, Caucasians, Orientals--all are equally impoverished in Cuba. The city at first did not strike me as very clean, but the shortage of goods made people use the most of what they had. You could tell they tried to take good care of the buildings even if they were partly damaged, which I thought was admirable.

With the end of the Cold War in 1993, Cuba lost trade avenues as many of its communist trading partners transformed into market economies. But the country is gradually moving towards a market-oriented economy too, and the pace of the transition has been picking up in recent years. Cuba will likely experience significant economic development in the near future and when that happens, I'm afraid the delightful scenes I witnessed in the alleys in Havana will be affected as well. It may be selfish of me to say so as a foreigner, but I would be sorry to see the distinct features of the city disappear. My feelings aside, I believe Cuba will undergo significant changes in the next few years.

Costa Rica: Decision-making at a dazzling speed

We stopped in two cities in Costa Rica, San José and Heredia. In San José, the lecture took place at the Gold Museum and the workshop at Universidad Veritas. Then we moved to Heredia, where we held a lecture and workshop at Universidad Nacional.

The workshop at Universidad Veritas, San José

The lecture at Universidad Nacional, Heredia

The workshop at the Universidad Nacional, Heredia

The objective of the workshops in Costa Rica was the same as in Panama: producing a hat from materials at hand. Of the three countries we visited, the students here demonstrated the most sophisticated understanding of western concepts of design. While there were some differences between the students of the two universities, overall the workshop participants had things in common: a firm grasp of the aims of the exercise and the ability to turn out an exceptional piece of work.

As was the case in Panama, it was remarkable how fast the students set to work. Far from getting bogged down in planning, they worked so fast that, in the earlier part of the production process, when the hat was yet to take shape, I couldn't help but wonder if they knew what they were doing at all. Incidentally, the universities had a fine studio, and I was amazed to see that female students were at ease working with rather dangerous equipment.

Photos: Takumi Ota

Jin Kuramoto, Jo Nagasaka: Design Lecture & Workshop in Central America

<Schedule>

Panama (Panama City)

Monday, September 3 and Tuesday, September 4

Venue: Universidad Católica Santa María la Antigua

Cuba (Havana)

Thursday , September 6 and Friday, September 7

Venue: Instituto Superior de Diseño

Costa Rica (San José)

Monday, September 10

Venue: Universidad Veritas, and others

Costa Rica (Heredia)

Tuesday, September 11

Venue: Universidad Nacional

Jin Kuramoto

Jin Kuramoto

Product designer. Born in 1976 in Awajishima, Hyogo Prefecture. After graduating from Kanazawa College of Art, Kuramoto worked for a home appliance manufacturer before founding JIN KURAMOTO STUDIO in 2008. He designs furniture, home appliances, and everyday goods for both domestic and overseas clients. Kuramoto has won numerous awards, including the prestigious iF design award and Good Design Award.

http://www.jinkuramoto.com/

Jo Nagasaka

Jo Nagasaka

President of Schemata Architects. Born in 1971 in Osaka Prefecture. In 1998 he graduated from the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Fine Arts of Tokyo University of the Arts, and established the architectural firm Schemata Architects. In 2007, he started a collaboration office called HAPPA that shares a gallery, shop and other facilities with the firm. Nagasaka is known for works that are simple yet have unconventional design concepts.

http://schemata.jp/

Back Issues

- 2024.11. 1 Placed together, we …

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2024.2.19 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.10.24 Inner Diversity <2> …

- 2022.10. 5 Living Together with…

- 2022.6.13 The 48th Japan Found…

- 2022.6. 3 The 48th Japan Found…